Comrade Saibaba: A Fearless Teacher

I first met G.N. Saibaba and Vasantha shortly after their marriage thirty years ago. At that time, Saibaba was a research scholar at the English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU) (then Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages [CIEFL]). I was a research assistant in a project at the Anveshi Research Centre for Women's Studies, an autonomous women's studies centre located at the Osmania University Campus. Anveshi's library had many unique English books on feminist, political and economic topics, and many students from the Central University of Hyderabad and EFLU would come there regularly to study and attend meetings. The space allowed for constant interaction with academicians, intellectuals, writers and activists from across the country and abroad. It was very exciting for many activists and students. One such memorable meeting was when I met Saibaba and Vasantha for the first time.

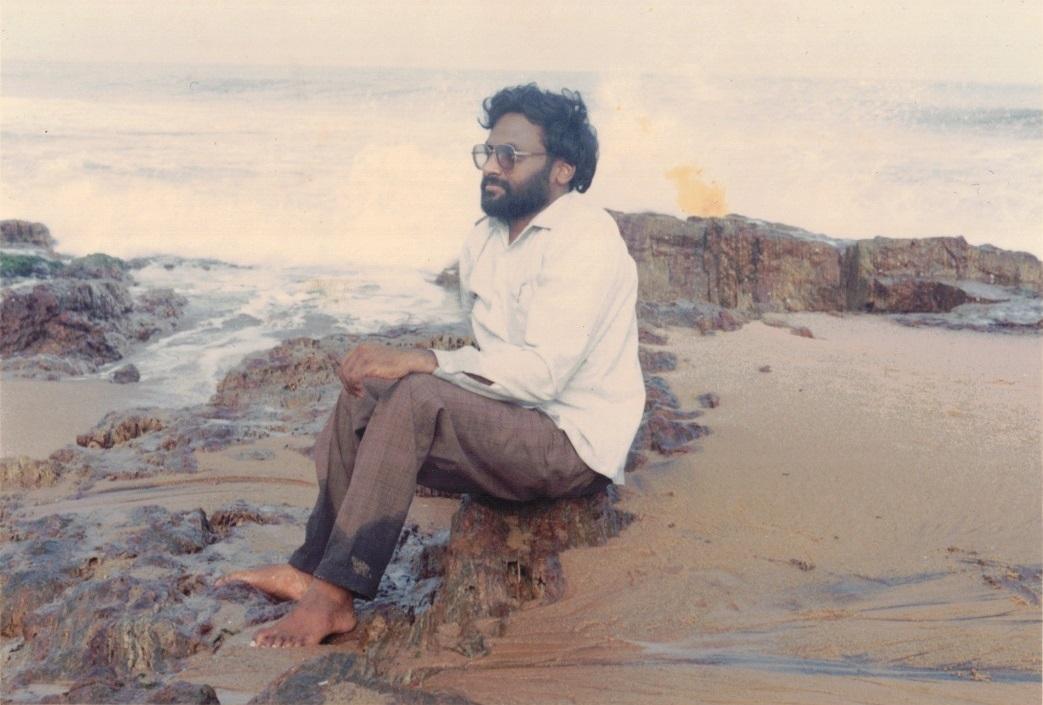

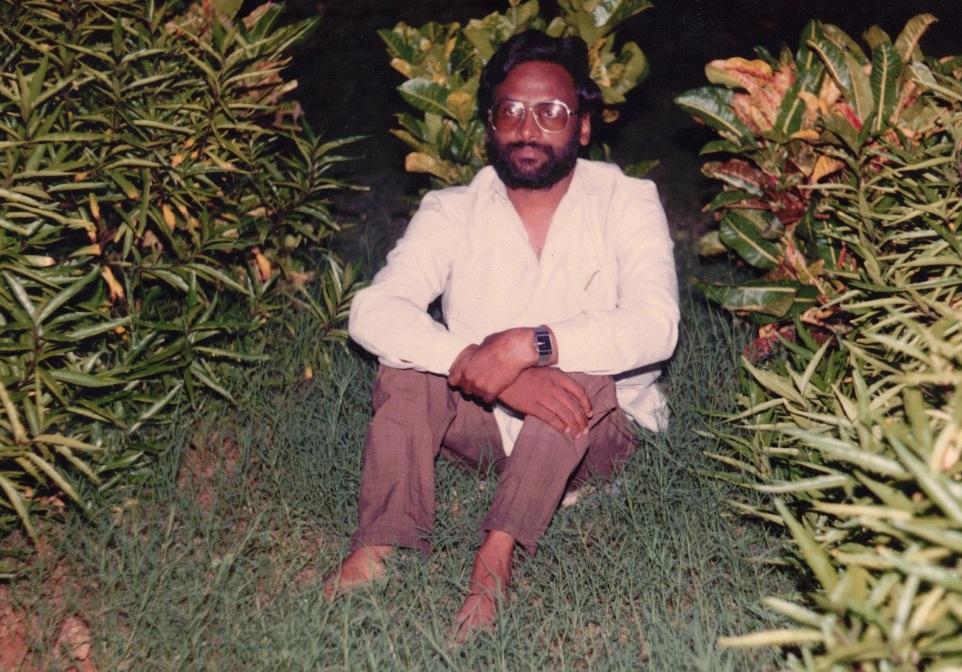

When we first met, Saibaba was not a wheelchair-user. He used to walk with the help of his hands, wearing slippers. Having been afflicted with polio in his early childhood, his legs were very thin and weak. Someone would drop him on a scooter at the library in the afternoon, where he would read for about three to four hours, and then pick him up again in the evening. At the time, Vasantha also worked as a field research assistant in Area Studies at Osmania University for a year on Reproductive Health. The young couple would attend civil rights meetings in Hyderabad together.

The time of the 1980s and 1990s was a period of vibrant civil movements. As contemporaries in different fields of activism—I was a full-time independent journalist and women’s rights activist—we frequently stood together in solidarity, defying constraints and understanding questions of subaltern groups and classes. At that time, in Hyderabad, Sai's hunger strike for political prisoners created a discussion among many people. The fighting spirit that he showed beyond his physical disability increased the respect all of us felt for him.

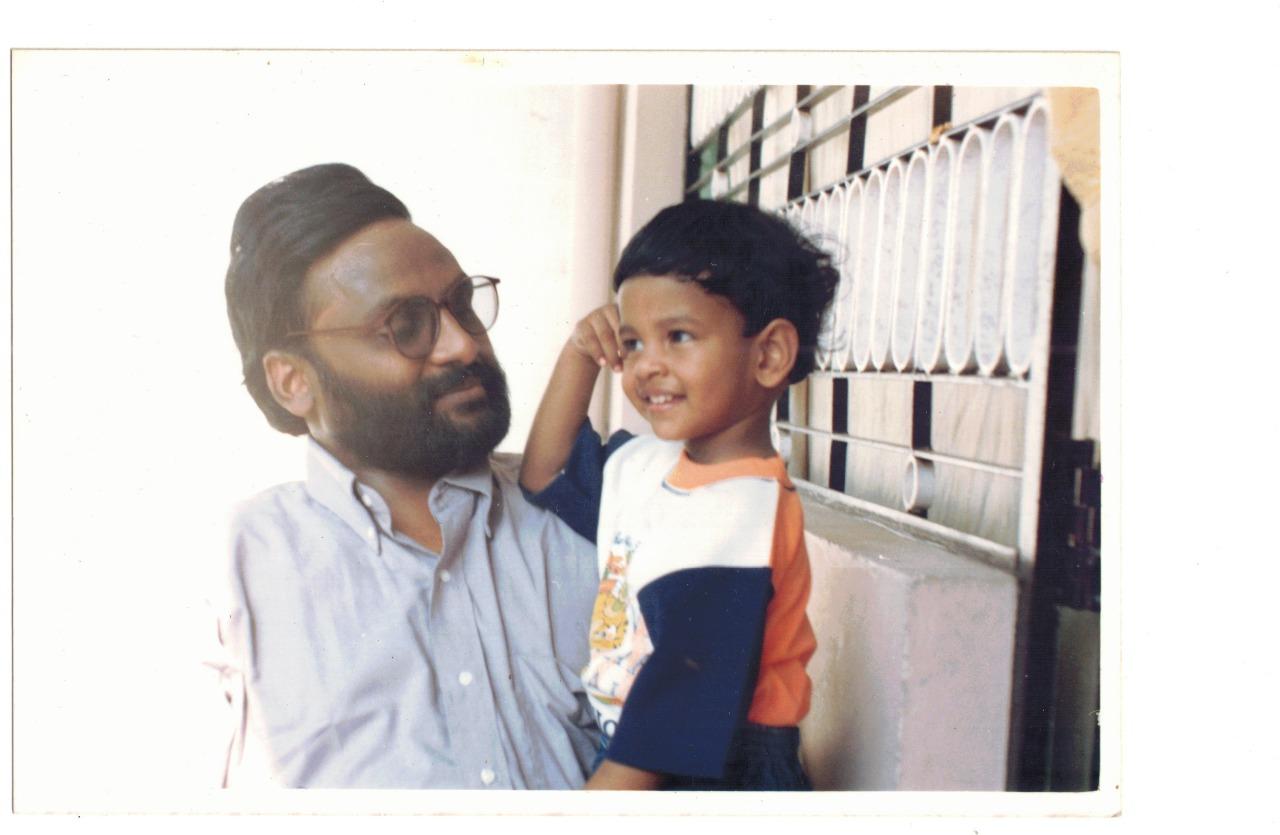

However, the pressures of work sometimes kept us away. I was unable to meet Saibaba and Vasantha’s daughter, Manjeera, when she was born. (In fact, I saw Manjeera for the first time only two months ago in Hyderabad at the NIMS Hospital.) Subsequently, Saibaba joined Delhi University as a faculty member in the English department. When Rohith Vemula died at the Central University of Hyderabad, a big gathering was held at Jantar Mantar in Delhi in 2016 demanding justice. I met Vasantha there after many years, and for the first time, I also met Professor Shoma Sen, who would also go on to be detained for years under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). By then, Saibaba had already been arrested and jailed in Nagpur with many false allegations under the draconian UAPA.

While we used to join protest gatherings and solidarity meetings for Saibaba in Hyderabad, we rarely kept up with Vasantha. Saibaba's mother and younger brother, Ramdev, along with Vasantha and Manjeera, bore the burden of these ten years of detention from outside.

When Saibaba was released in March this year, I asked Vasantha if we could meet when I came to Delhi. She said “yes” immediately. I went to their house along with three other friends who are also social activists and academics. None of them had any direct contact with Saibaba previously, and yet both Vasantha and Saibaba received all of us very warmly. For almost two and a half hours, we were moved to tears as we heard from Saibaba himself about his experiences in the jail. He spoke about the atrocities in the anda cell (egg-shaped cell) of Nagpur Central Jail and the inhuman conditions in which he was jailed for a decade on trumped-up terrorism charges. A friend who came with us could not contain her grief and wept. Vasantha also listened to those experiences with surprise. Saibaba did not even get time to sit with her and talk to her calmly after being released. He had started going to AIIMS every day and underwent physiotherapy. His left hand was almost non-functional. That was due to the damage caused by the police forcefully grabbing and dragging him when he was arrested. Taking him to physiotherapy every day, and making arrangements for people coming for interviews, Vasantha said that she was hearing many things for the first time along with everyone else.

In these ten years of prison experience, more than ten tribal prisoners have passed their graduation under Saibaba’s guidance. Our eyes got wet listening to how much Saibaba's daily life has helped people even in miserable places like the anda cell. We told him that he should record all of this. He accepted immediately. It was a great experience for us to meet both of them in their house, to talk and eat together. We said we would meet him again.

We did not think that day that Saibaba would be physically present for only six more months! In fact, within the short time that Saibaba was with us, we had noticed that he was struggling physically. But Saibaba wanted to talk. For ten years the state carried out a cruel mockery of his disability without hesitation. No medical help was received. He said that there was no such thing as nutritious food; people ate whatever food was given there because they needed to survive. The ten years of imprisonment shortened his life. The body was destroyed inside. Even the basic things that should be given to disabled people were denied. He described his daily life in prison to us in minute detail. Prison officials would give them a chance to come out of the cell only in the morning. The inmates would complete their routines and wait for that time as they did not want to miss those hours. He said that even if there were any quarrels between the fellow prisoners, they were all friendly with him, and perhaps his physical condition also contributed to that. Writing petitions for fellow prisoners and teaching them, he remembered the things that kept him alive there.

When I mentioned that I had translated Bhasha Singh's Unseen, a book on manual scavenging, into Telugu under the title Asuddha Bharath, he shared that in prison too, work was divided along caste lines. Safai (cleaning) work was done entirely by Dalits, and caste universalism was strictly enforced in prisons. We were not surprised to hear that. We continue to see how caste intertwines with inequality in different ways in our everyday lives.

During those ten years, his fellow prisoners took care of him as much as they could. He said that he wrote the necessary petitions for completing their formal education and taught them so that some of them could even graduate. Even there he stood firm for democratic rights despite the detention making his body weaker. A beautiful smile graced Saibaba's face as he said that secret praises from prison staff, along with fellow inmates, were regenerating and life-giving during his incarceration. However, senior police officers were constantly on alert in order to keep him under control. Saibaba mocked not only his disability but also the state's imprisonment.

In a poem titled “Why Do You Fear My Way So Much,” written to Manjeera on May Day in 2019, he asked:

“Memories abound

the tracks of history.

Socrates was given a glass of hemlock.

Galileo was walked upto the gallows

for mapping the skies

defying the sun going around the earth.

Hikmet was incarcerated

for the Turkish soldiers

read his poems hidden

under their pillows in army barracks.

Faiz almost faced the death sentence

for he sang paeans to labouring hands.

Déjà vu...Déjà vu...

Seeing the poet handcuffed

and walking through the gates

of an imprisoned court of law,

a dazed scribe of eminence

cried, heartbroken

tears rolling down his cheeks.

Decades have passed.

Why Do You Fear My Way So Much?"

However, when the state did not allow him to see his mother for the last time before she died, it had a great impact on his mental state. That sadness and grief haunted him for many days, and tears did not stop whenever he remembered his mother. Although happy to be released from jail, he wanted to take control of his health, write about his experiences, elaborate and work on his writings that had stopped in these ten years, and spend more time with his wife, Vasantha, and daughter, Manjeera.

He wanted to help Manjeera with her PhD studies. Who shall answer for the charges levelled against him, which have taken more than ten years out of his personal, professional, academic and combative life? When he came to Hyderabad, he was eager to improve his health and hoped to explore naturopathy soon after the surgery. But nobody understood until he was gone forever that ten years of state imprisonment had made his body even worse. That is the tragedy.

What answer can we give to Vasantha, who wrapped us in tears and said, “He did not say goodbye and did not even give us a last kiss”? Vasantha faced several hurdles to bring Saibaba out from prison alive, but now he is physically absent. Yet, he gave her the courage to continue her journey.

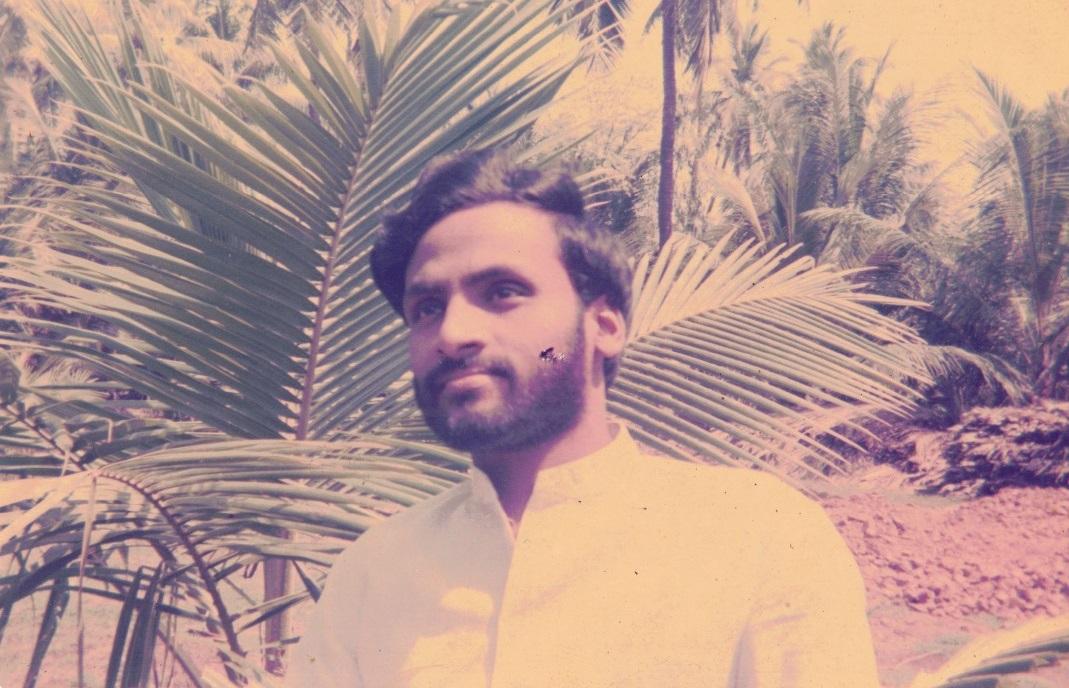

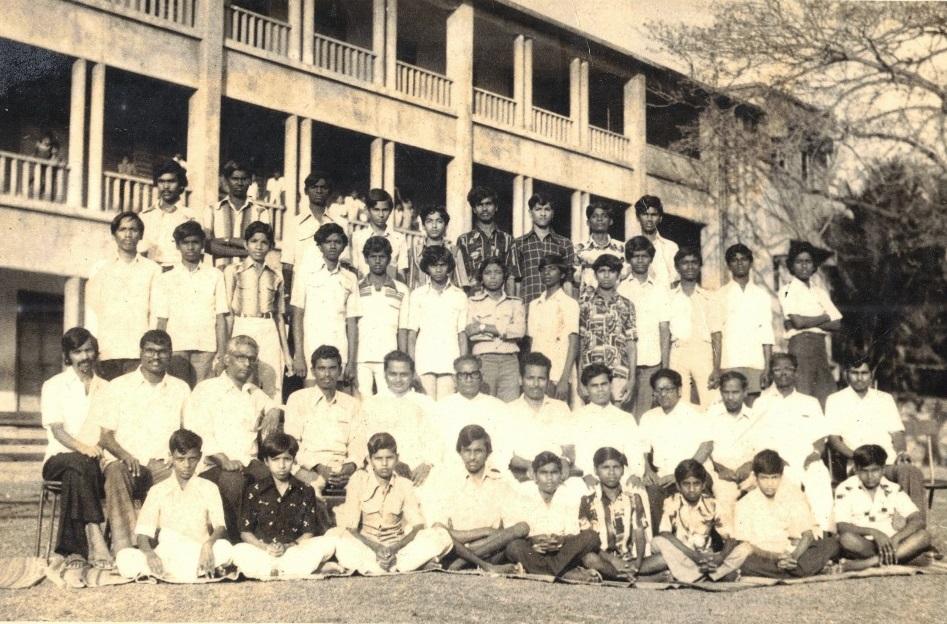

If images from Vasantha’s family albums remain tangible forms of memory-keeping, seeing young students from different parts of the country come to pay their respects to Saibaba—hundreds of them walking in Saibaba's funeral procession—is a reflection of their democratic aspirations and of his lasting legacy.

Comrade Saibaba is not dead. As per his wish, his eyes and body have been donated for medical research purposes. I was given the responsibility of handing over his body to the hospital, for which I am very grateful to his family members. Like he did in jail, now in death, he is conducting a silent conversation with hundreds of medical students using his own body as a lesson! In his own words,

“I still stubbornly refuse to die

The sad thing is that

They don't know how to kill me

because I love so much

The sound of growing grass"

To learn more about political prisoners, read Najrin Islam’s essay on Sofia Karim’s Turbine Bagh and Ketaki Varma’s interview with photographer Masrat Zahra.

Images courtesy of Vasantha, widow of Professor G.N. Saibaba.