The Earth Walked with Them: Rebellion and Trauma in Amma Ariyan

Purushan, the protagonist of Amma Ariyan (Report to Mother, 1986), travels along the length of Kerala to inform his friend Hari’s mother of her son’s tragic death. As his odyssey draws to a close, Purushan breaks away from the rest of his group and walks into the church where Hari’s mother attends a baptism. Alone for the first time since he set off on this journey, Purushan regards the Stations of the Cross, as the priest is heard asking, “Do you know how serious your duty is?” There isn’t a more poignant question to be asked—not of Purushan, who is struggling to come to terms not only with Hari taking his own life but also with his role in the Naxalite insurgency in Kerala, his torture at the hands of the police and the surging wave of radical left-wing politics in the state. And not of the viewers, who tacitly accompany Purushan on this journey that entwines the personal, the political, the historical and the radical.

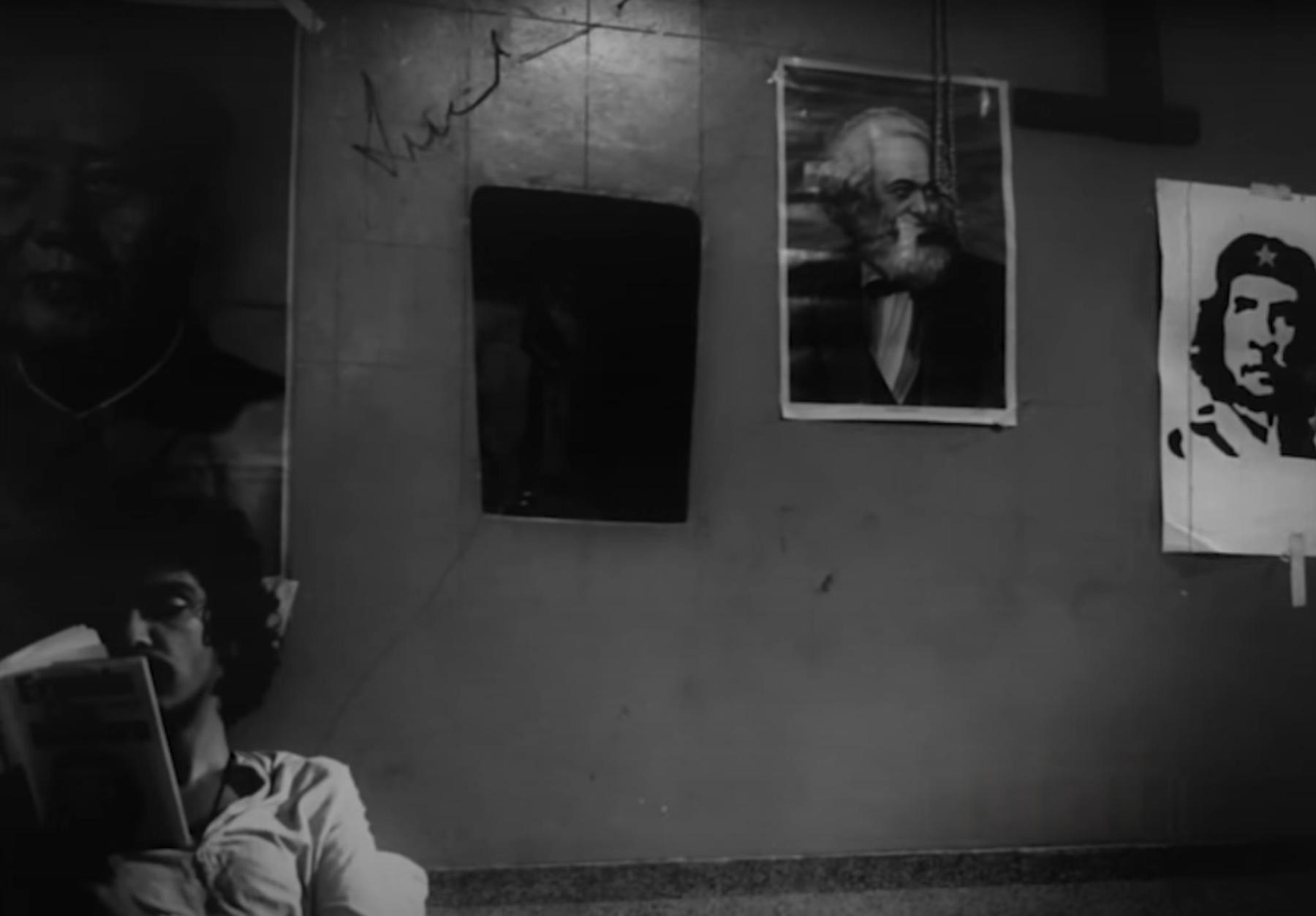

The final work of John Abraham, Amma Ariyan accents a non-linear fictional narrative with cinéma-vérité reports of ongoing and historical workers’ struggles, traversing the political and geographical landscape of Kerala. Screened as part of Dr. Omar Ahmed’s insightfully curated Rewriting the Rules: Pioneering Indian Cinema after 1970 at the Barbican, Amma Ariyan is rooted in the Parallel Cinema movement of the 1970s–90s. Ahmed’s framing of the tradition as the “first true decolonial filmmaking practice” of post-independence India and his astute contextualisation of this within the politics of the Naxalite movement allows for a rich understanding of the aesthetic and political language of Amma Ariyan. Ahmed posits that the film responds to the trauma of militant insurgency and the state’s brutal reaction to it by politicising the figure of the Mother, positioning her as central to the revolution.

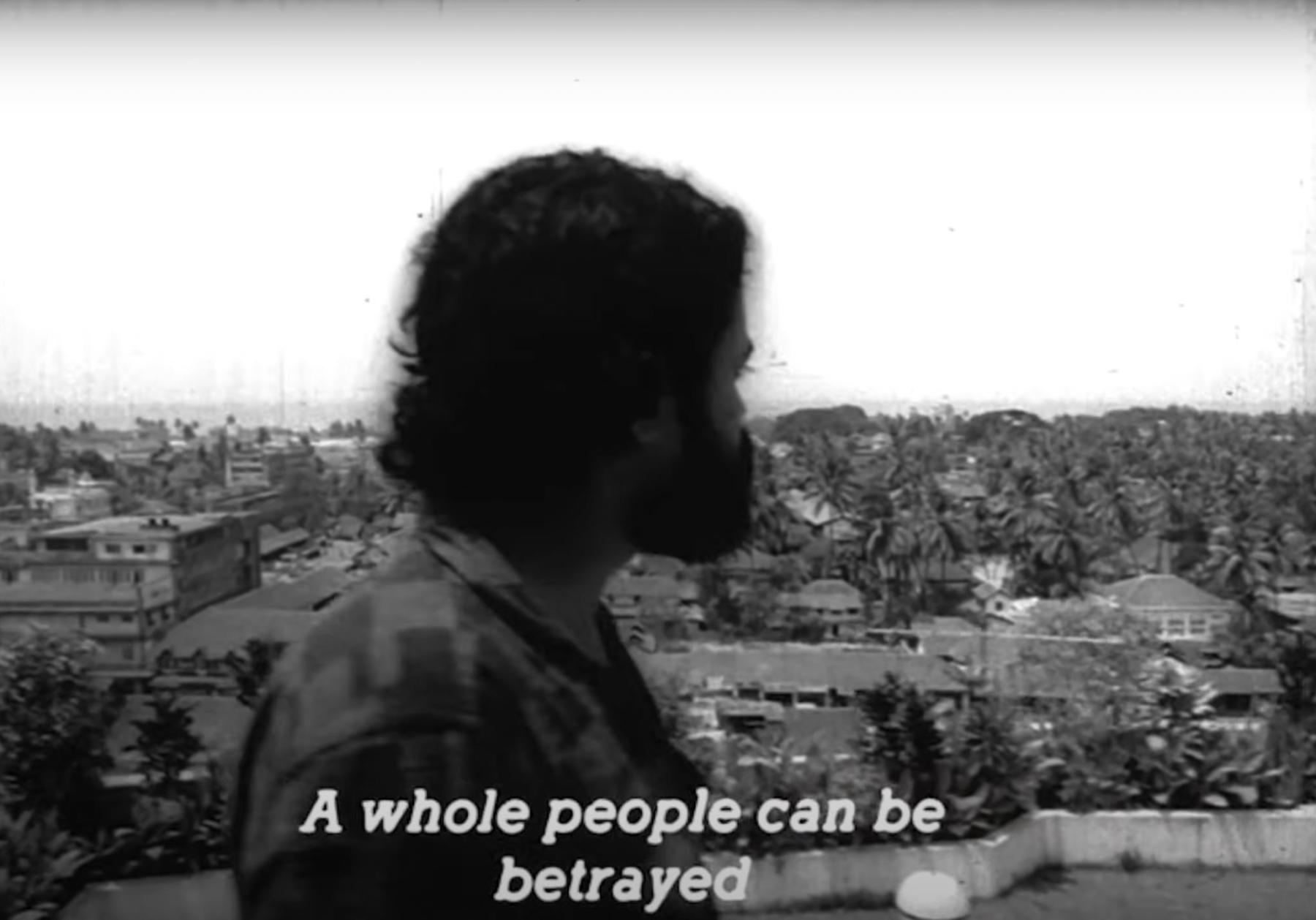

Indeed, the film is not only bookended by the Mother—silently watching her son leave, facing the camera in defiance at the news of her son’s death, or watching the film being screened in the last shot. It is also punctuated by her. In many of the sequences, as Hari’s friends and comrades join Purushan’s quest, other mothers are left behind, remembering Hari like they would their own child. From a small group of people amassed by Purushan to first identify Hari’s body, the band grows with each stop along the trek between Wayanad in the north of the state, where Hari’s body was found, to Fort Kochi in the south, where Hari had grown up and his mother still lived. To this figure of the Mother, then, there is a palpable complement in the film through the motif of the land.

The film begins with Purushan setting out for Delhi, a journey that does not transpire on screen, and ostensibly never does for him. En route to picking up Paru, his partner, the road takes Purushan to Wayanad, where he comes across the police surrounding Hari’s lifeless body. “He hanged himself, on that hill, there,” a local villager tells Purushan, locating the trauma of Hari’s death in the landscape that gave testament to it. When Purushan decides to forfeit his intended journey with the sole purpose of informing Hari’s mother, although he does not yet know who she might be, the film embarks on its non-linear narrative route.

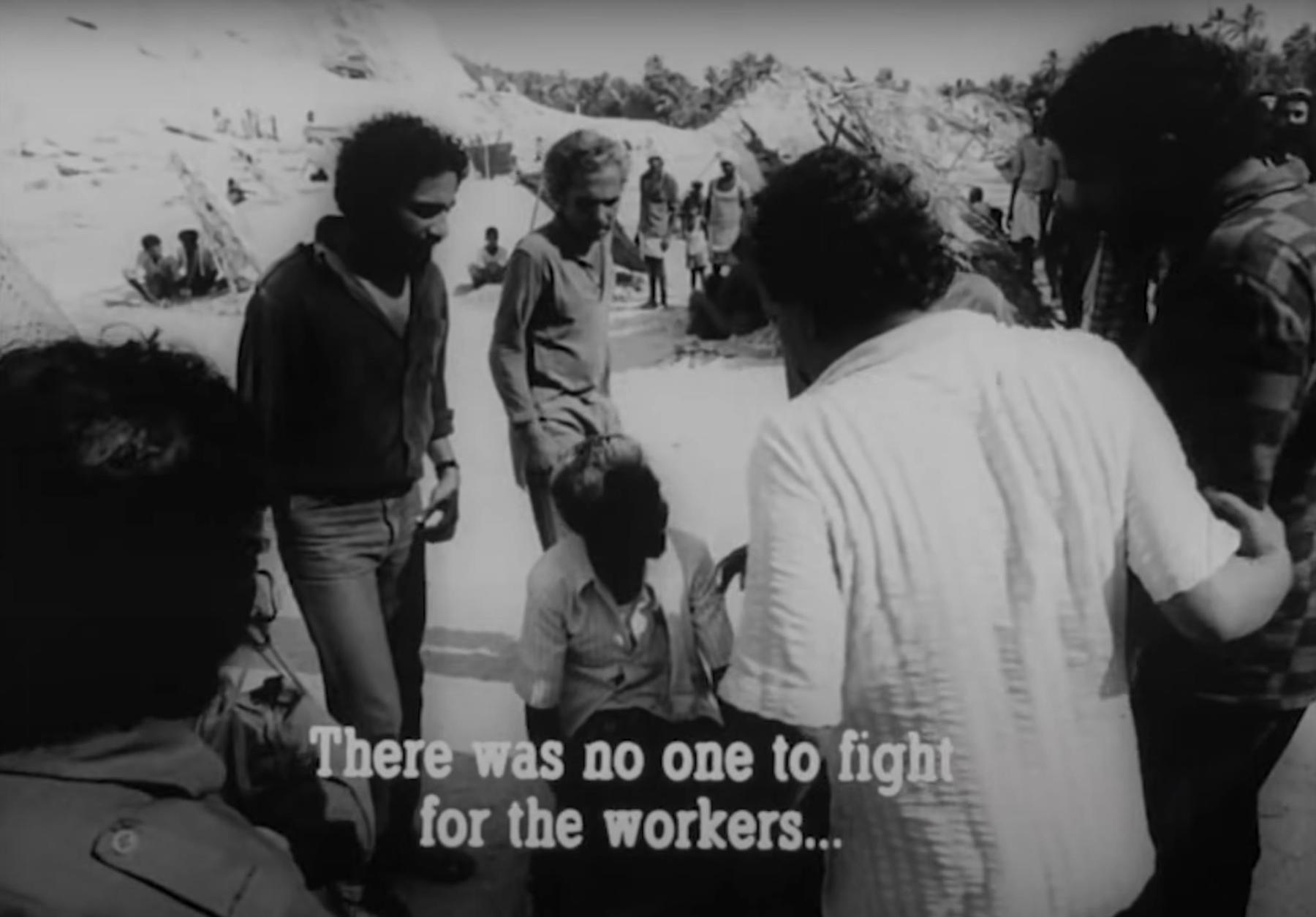

His time in Calicut is underscored with the protests of medical college students, who are fighting the ongoing privatisation of education, and artists chanting, “Free Nelson Mandela!” When the group reaches the ancient port of Beypore, we witness fisherfolk organising against mechanised trawling. Near Kuttippuram, we hear of Karuppaswamy, a quarry worker who lost his limbs at work, and the workers who fought for him. Thrissur, Kodungallur, Kottapuram and Vypin—every location is imbued with a narrative layer, be it personal, drawn from folklore, or yet another history of oppression met with collective resistance.

As the group reaches their last stop, Fort Kochi, the scale of this layered narrative unfolds too. It is this street, where four fisherfolk were killed; it is this neighbourhood in Mattancherry where three people were murdered by the police during the port workers’ uprising of 1953; it is this godown where women workers faced a violent police force to fight a losing battle for their rights. These streets, Abraham seems to say, are haunted by the trauma of inhuman oppression at the hands of the ruling classes, a trauma that goes on to this day, just as they reverberate with the resistance of the oppressed, ringing with their chants of Inquilab Zindabad! (Long Live the Revolution!)

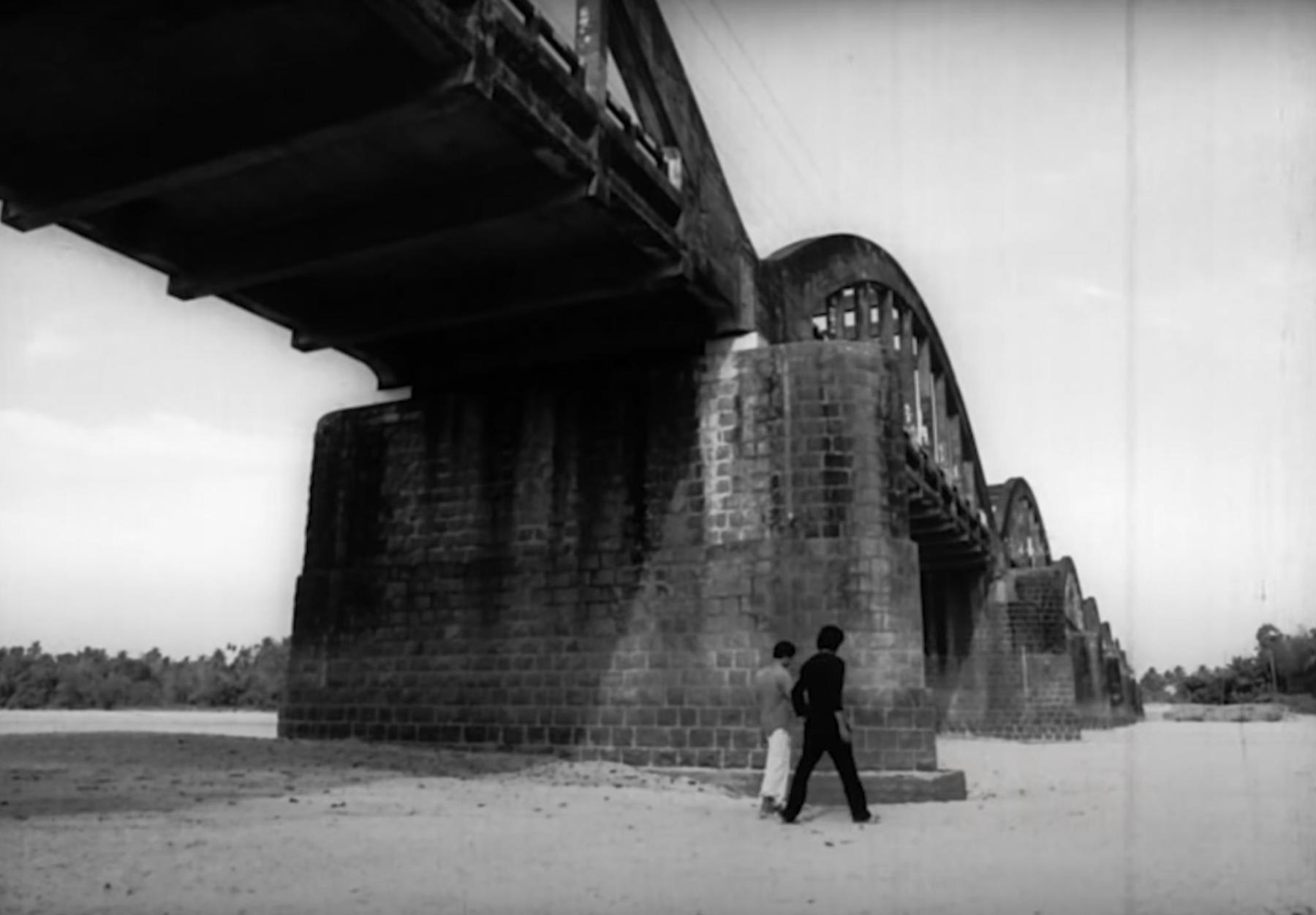

Hari’s life, too, is traced not chronologically but through this cartography. The first time we see Hari alive, as he was, he walks along the sandy expanse under the Kuttipuram Bridge, which connects Calicut to Kochi, already indicating the trajectory of the film’s journey. Through these spaces permeated with trauma and rebellion, we learn of Hari’s life, his music and politics. There is a tangible link, too, between these geographies of trauma and the means of the production of Amma Ariyan. Ahmed highlighted how the Odessa Collective, the banner under which Amma Ariyan was made, toured Kerala from village to village, screening films on a 16mm projector, and used public contributions to finance the film.

This is not to say that Amma Ariyan is beyond criticism. One might point to the relegation of women to the role of mothers in the revolution or to the whisper of disillusionment, which continues to be used as a narrative device to discredit radical movements. One might also argue, however, that reading Amma Ariyan solely through the lens of political messaging would be a fallacy and a disservice to the film. It is not only Purushan’s journey in the film, but the journey of making the film itself that is an act of rebellion and of reclaiming space. There is no question as to where the heart of the film lies—with the people. Nothing illustrates this as clearly as the film’s simple rendition of Otto René Castillo’s “Apolitical Intellectuals”:

They'll ask:

“What did you do when the poor suffered, when tenderness and life burned out of them?"

Apolitical intellectuals of my sweet country, you will not be able to answer.

To learn more about filmmaking collectives in India, read Ankan Kazi’s essay tracing the growth of filmmaking collectives since the 1970s and Najrin Islam’s conversation with Kasturi Basu of the People’s Film Collective. To read more about political education, read Ankan Kazi’s essay on the Mukti Bahini and Arushi Vats’ article on the Sahmat Collective.

All images are stills from Amma Ariyan (1986) by John Abraham. Images courtesy of the artist.