Free Jazz: Soundtrack to a Coup d’État

Poster for Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat (2024).

If Sergei Eisenstein’s October (1928) were intended as a film about a (failed) revolutionary struggle of decolonisation in the Third World, Johan Grimonprez’s Soundtrack to a Coup d’État (2024) would be it. Like October, the Belgian director’s historical documentary exploits the political potential of rhythmic montage to reveal the nonlinear and dialectical movement of history, and the various contingent forces that determined the path it actually took—genocide and a protracted civil war—over another it could have taken but did not—national liberation and socialism.

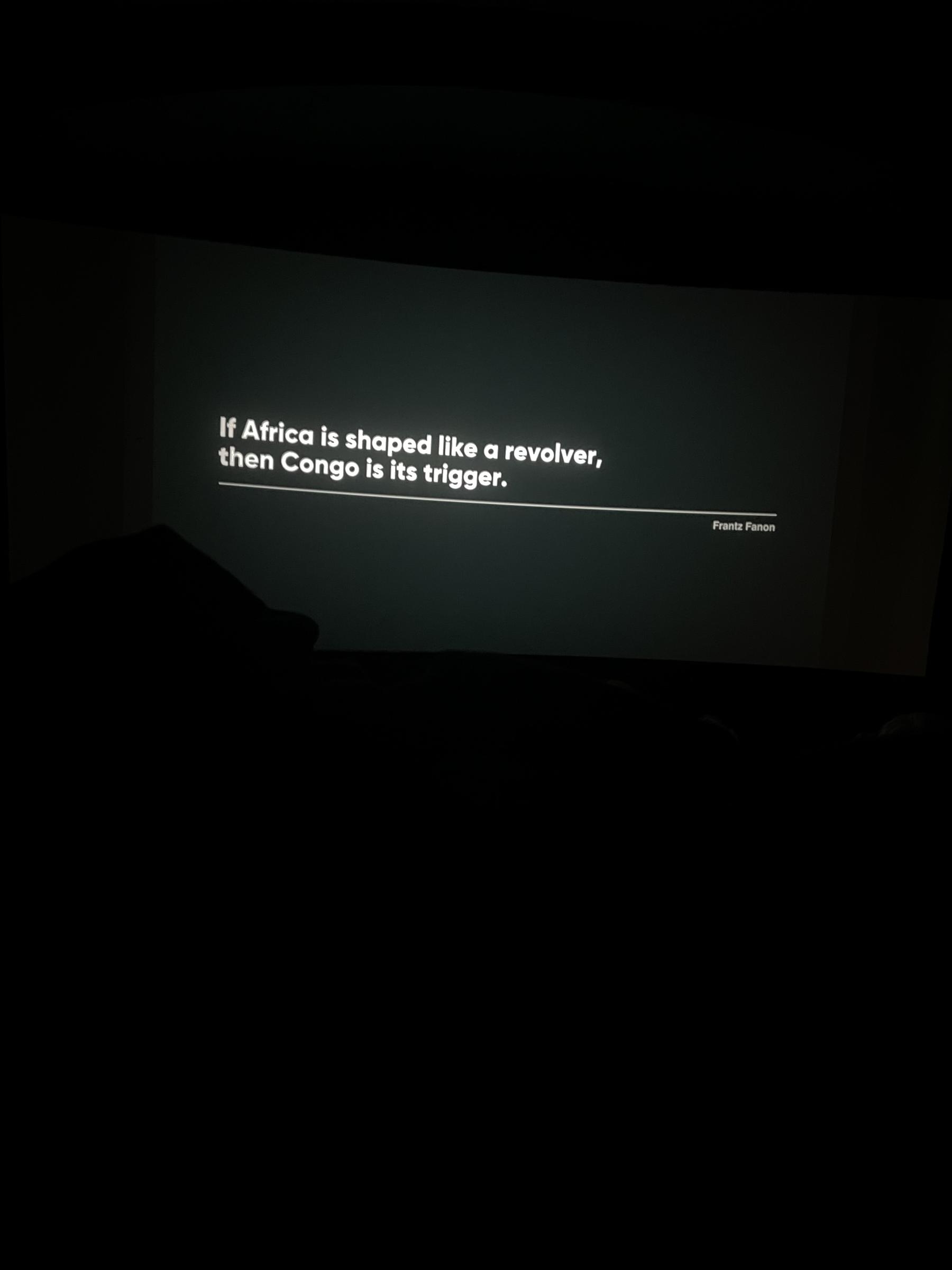

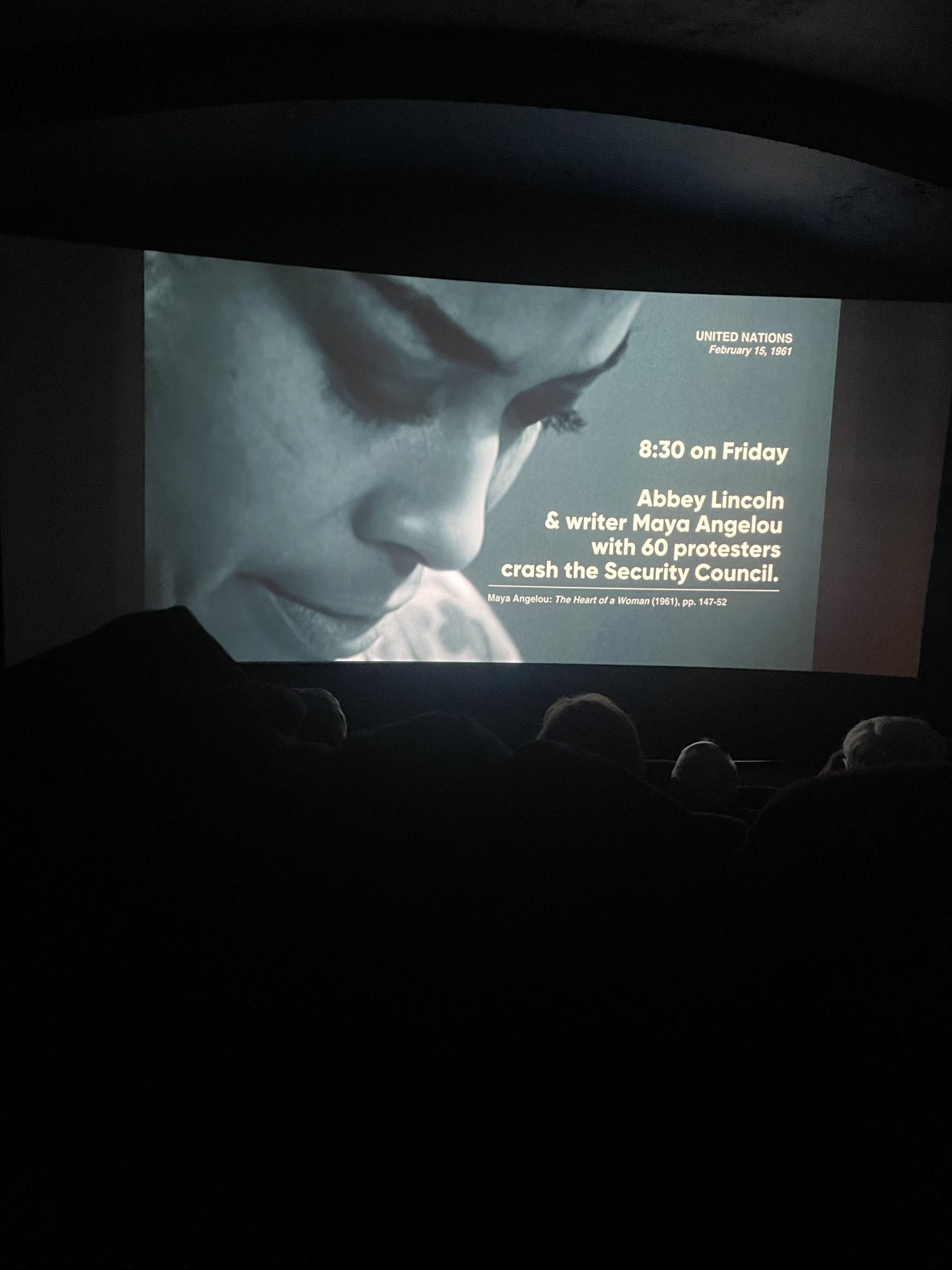

Still from Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat at a screening. (Photo by author.)

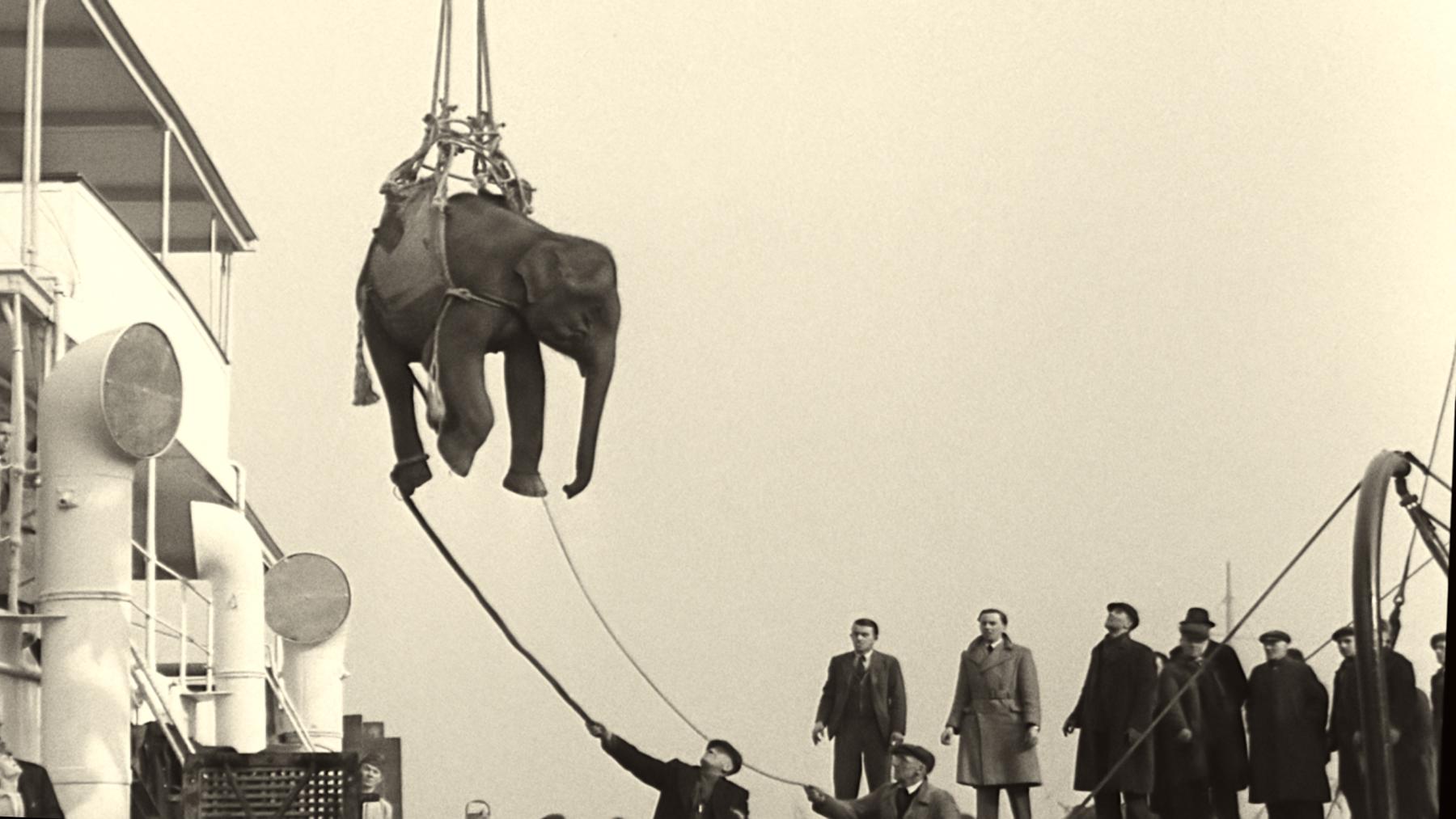

In the context of Patrice Lumumba’s newly independent Congo, Soundtrack follows the travails of the pan-African vision of a United States of Africa and the imperial capitalist conspiracy that ended in the nation’s demise. That is, the conspiracy of the US, Belgium and the unofficial “Congo Club” at the United Nations (the band of representatives of the most powerful nations who controlled the world for their own economic gain) to overthrow the democratically elected Lumumba. They bolstered his conservative opponent, Moïse Tshombe, in a bid to regain control of uranium mining necessary to produce atomic bombs.

This resulted in Lumumba’s carefully orchestrated assassination and a long period of social upheaval. The film reconstructs this episode from the Cold War in which the colonialists’ choice of weapon was, as a New York Times critic put it, “a blue note in a minor key,” or in Dizzy Gillespie’s words, “a cool weapon”—Jazz. But jazz is not simply the film’s subject, it is also the vehicle of its movement—its form.

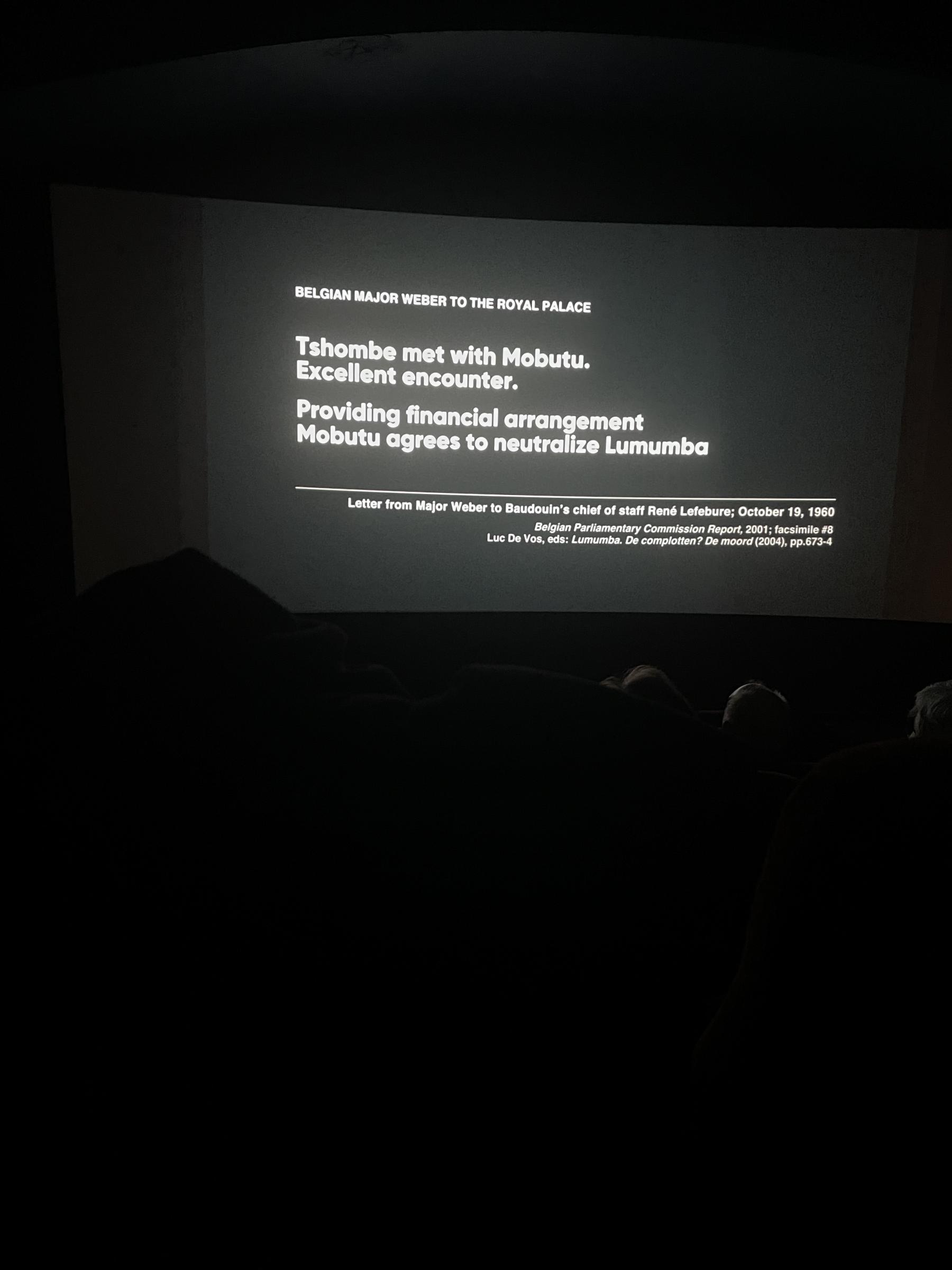

Still from Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat at a screening. (Photo by author.)

Assuming the structure of a jazz number, Soundtrack traces the movement of history analogically within the music genre’s formal limits: its fluidity, dissonance, syncopation (jazz’s signature feature of playing notes on off-beats) and polyrhythmic improvisation. From the outset, it orients the viewer through the whirlwind of Cold War relations by staging the introduction of the documentary’s main protagonists—all jazz musicians—as if they were members of the same band. Scenes from memorable concerts and interviews are suddenly arrested with title cards introducing the documentary’s cast: Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie.

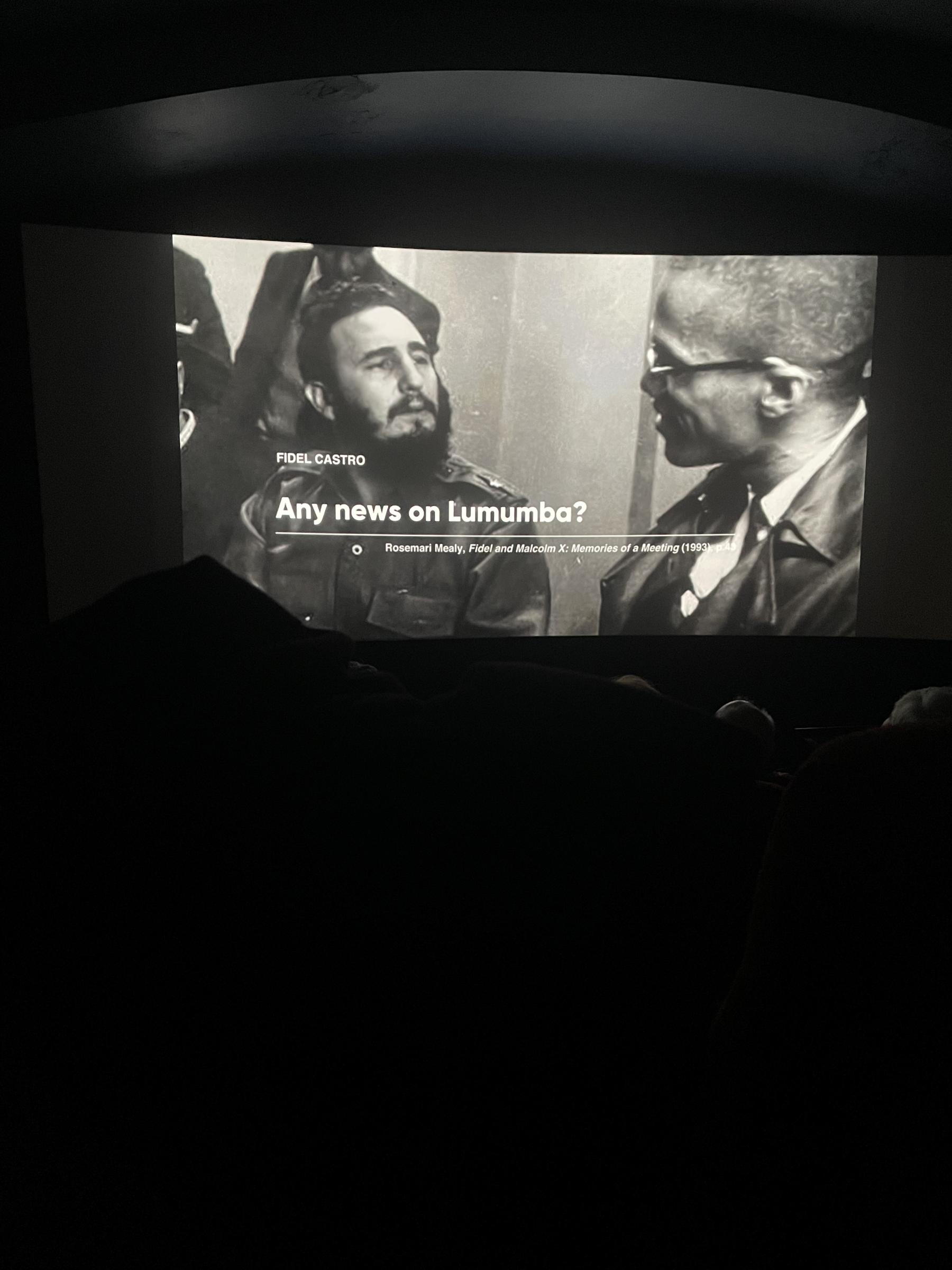

Still from Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat at a screening. (Photo by author.)

This unlikely list of characters is interspersed, or, rather, syncopated, with the film’s supporting cast of politicians, diplomats and militant intellectuals, including, most consequentially, Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo; Andrée Blouin, chief of protocol in Lumumba’s government and militant feminist; Nikita Khrushchev, premier of the Soviet Union; Malcolm X, Black power intellectual and revolutionary; Dwight D. Eisenhower, US president; Allen W. Dulles, CIA director; Dag Hammarskjöld, secretary general of the United Nations; and the group of non-aligned politicians Kwame Nkrumah, Fidel Castro and Gamal Abdel Nasser. A panoply of footage and audio commentary from the personal archives of Khrushchev and Blouin, concert recordings, television broadcasts and period advertisements, as well as quotes from top-secret cables, memoirs and a wide range of academic publications, produce this cognitive map of social forces in and around 1960s Congo.

If this documentary were to be reduced to its content, its subject would be the weaponisation of jazz toward imperial goals. From the mid-1950s, the American State Department and the CIA dispatched some of the most prominent voices in jazz, such as Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie and Nina Simone, to the African continent to serve as ambassadors of a spurious freedom (the freedom of the market in liberal democracy) while the US government bolstered African elites who shared American economic interests in the Congo—a class Frantz Fanon derided as the national bourgeoisie—to continue extracting the uranium it needed to produce nuclear bombs. The US government went to great lengths to carry out this mission, for instance, by funding Dizzy Gillespie’s 1964 campaign to run for president of the United States—a publicity stunt for which he produced a variation on his song “Salt Peanuts” (recall that earworm refrain “Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!”)—with a proposed cabinet of jazz musicians and Malcolm X as the attorney general before later withdrawing from the race.

Still from Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat at a screening. (Photo by author.)

On the level of content alone, Soundtrack suggests that Gillespie was complicit in his country’s counterrevolutionary tactics. Nina Simone was likewise duped by the American Society of African Culture, a CIA front, which sent her to Nigeria in 1961. Armstrong, too, seemed to know—however begrudgingly—that he was being sent to Africa in 1960 on a propaganda mission, though his band only learned about the planned coup against Lumumba (with whom they personally sympathised) while staying with the prime minister’s opponent Moïse Tshombe in Congo.

Still from Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat at a screening. (Photo by author.)

But whether jazz’s Cold War instrumentalisation was disavowed (as an unknown known), misconstrued (a known unknown), or undiscovered (an unknown unknown), it was never merely an ideological tool. Its contradictory character as both an instrument of a sham freedom and an art form borne out of the struggle for freedom from slavery gives Grimonprez’s narrative, essayistic film its texture. Rather than moving chronologically (from national independence to assassination; or big band to bebop) as the film’s content alone might suggest, Soundtrack assumes the recursive improvisational structure of free jazz. This is apparent in the film’s beginning and ending, in which Abbey Lincoln’s shrieking and screeching to Max Roach’s staccato drums on We Insist! Freedom Now Suite is interspersed with footage of angry protestors, including Lincoln, Maya Angelou and another sixty people, who crashed the United Nations Security Council meeting after Lumumba’s assassination.

The montage of concert and protest restores to jazz its liberatory character; not the instrumentalised big band jazz performed for a predominantly elite white audience, but free jazz, and free in the dual sense of the term. In Grimonprez’s documentary, the unforeseen gaps and shifts in Freedom Now Suite find a visual counterpart: Among shots of relatively equal length, an excerpted advertisement for an iPhone (produced with natural resources extracted from the Congo) appears as a flash, a return of the repressed. Shortened to mimic the jarring effect of a glitch, such interruptions break with the metonymic fluidity of visual associations. The distant memory of Lumumba’s assassination returns from the repressed but ongoing history of extraction.These glitches conjure irruptions of revolutionary time—or, at the very least, their possibility—from within history and attest to jazz’s historical role as a cypher of a true but fragile freedom.

To learn more about political histories of music, read Upasana Das’ conversation with Shahbano Farid about the film Karachi at Night (2024), Pramodha Weerasekera’s contemplation of music and solidarity in Sri Lanka, Arundhati Chauhan’s album of Maoists’ production of revolutionary songs in Nepal, and Silpa Mukherjee’s essay on disco music and the diaspora. To read on failure, read Kshiraja’s essay on rebellion and trauma in Amma Ariyan (1986) and Anisha Baid’s reflections on artists’ exploration of the glitch as a site of possibility.

Images are stills from Soundtrack to a Coup d’État (2024) by Johan Grimonprez. Images courtesy of the director unless mentioned otherwise.