At Harkat Studios: A Space for Imperfect Cinema

Poster for 16mm Film Festival. (Mumbai, 2024. Image courtesy of Harkat Studios.)

It is noon when I arrive at Harkat Studios’ Aaram Nagar location. The production house and boutique studio is tucked away in a quiet corner of Versova, once home to Partition refugees and now populated by casting agencies and alternative art spaces. It is the third day of the 16mm Film Festival, a celebration of “everything analogue and photochemical” now in its eighth year.

In a city synonymous with cinema, the absence of spaces for independent film is conspicuous. Critic Ashvin Devasundaram describes contemporary Bollywood as a cultural and economic monolith, holding a “monopoly over [...] modes of production, distribution, exhibition and capital generation.” In the narrow creative field thus constructed, “a ‘one-size-fits-all’ national narrative” comes to stand for the majority of cinematic production, so that the possibilities of independent expression are circumscribed by a commercially-oriented, and often majoritarian, mainstream. For those working with analogue film, crises of opportunity, resources and visibility are multiplied, compounded by a distance from an international analogue subculture. When Harkat Studios was founded in 2015, for instance, “collectivising,” as founder Karan Talwar tells me, “seemed to be the only way.” The studio was born to create space for Talwar and his colleagues’ own analogue film practice and, as an extension of this project, the 16mm Festival was imagined both as an opportunity for artists to screen their work and a year-end check-in for the studio. Perhaps owing to this ambitious mission, the festival consists of three densely programmed days, including dozens of screenings, a workshop and a performance.

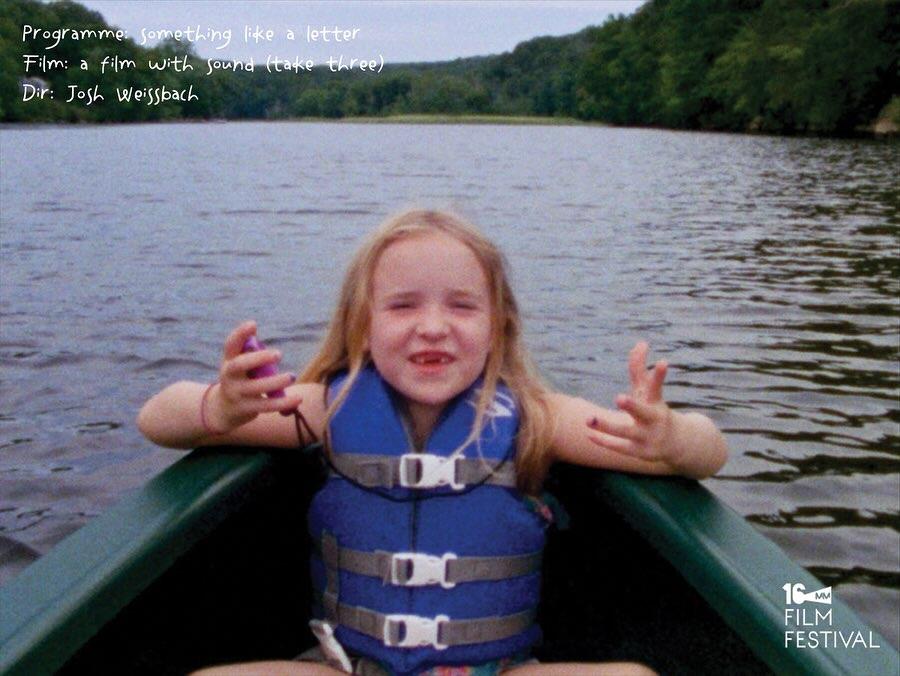

a film with sound (take three) (Josh Weissbach, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Harkat Studios.)

When I visit on the festival’s closing day, the offerings consist of a feature sandwiched between two short film programmes, beginning at noon and ending in the late evening. First on the docket is a set of eight short films, ranging in length from anywhere between two and twenty-four minutes and set in locations as diverse as Mexico City, Guangzhou and Berlin. Thematically, there is very little that links these films: they cover everything from marine expeditions to motherhood and historic acts of violence. Yet what holds them together is a profound attention to analogue film as a medium and tool. Josh Weissbach’s a film with sound (take three) (2023), for instance, is a three-minute attempt by a father and daughter to make a movie with sound after a silent attempt the previous year. Shruti Chamaria’s Monotokens, similarly, is a study of chemically operated photo booths (or photoautomats) in Berlin, investigating the place of analogue photography in a digital present. In the flickering frames on screen, as well as in the preoccupations of many of the works, the materiality of analogue film is centred, the medium very much part of the message.

Image courtesy Harkat Studios.

Speaking of Harkat’s approach to curation, Talwar describes it as straightforward and collective. The studio opens submissions every year, and the curation, jointly executed by the studio’s team, is guided by what comes in. The selection criteria applied range from “political considerations of what needs to be said” to the need for accessible programming that can help Harkat sustain and grow its community. On the technical front, as on the thematic, the range of films is diverse: “From found-footage explorations to chemical manipulations, hand-drawn animation to multi-medium analogue films and beyond.” This focus on variety and the organic is visible everywhere in the studio’s approach. The festival programme introduces the space as one where “...film shares space with leftover lunch boxes, milk, condiments.” On the second floor, above the screening room, Harkat’s developing lab sits alongside a kitchen, both a space for the making of work and the living of life that enables it.

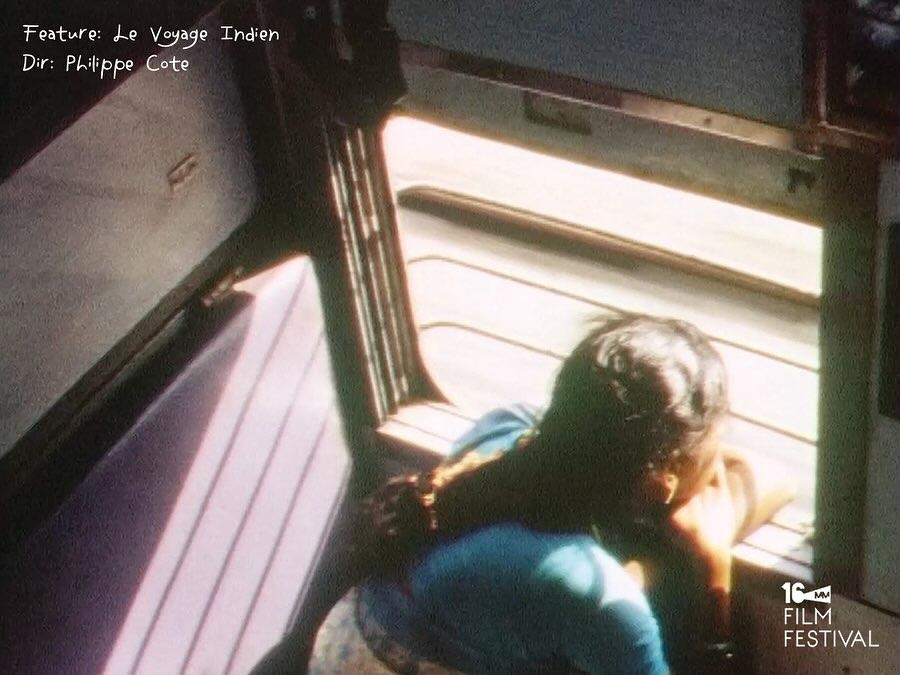

Le Voyage Indien (Philippe Cote, 2011. Image courtesy the artist and Harkat Studios.)

Addressing the multi-dimensionality of analogue film, filmmaker and critic Karel Doing describes it both as “a time-based medium, a strip that travels through a projector in a straight line from head to tail” and as a fundamentally plastic medium, one that, in its making and watching, “stretches out in multiple temporal, spatial and physical directions.” The day’s feature, French filmmaker Philippe Cote’s Le Voyage Indien (2011), is a film that captures this plasticity. Created by splicing together analogue documentation of two journeys across India—found footage from an anonymous traveller in the early 1970s and Super 8 footage taken by Cote in the 2000s—the film charts a meditative path across the country. The two sets of footage, interspersed and accompanied by ambient sound, generate a dream landscape, located in a geography that is at once familiar and not fully legible. In most shots, the camera is stationary, the attention fully on the natural rhythms of movement at each site—a temple, a beach, a train compartment—so that the viewer’s engagement with the film is guided by what the gaze naturally alights upon. Speaking of the generative possibilities of juxtaposition, film historian Nicole Brenez argues that “nothing clarifies an image like another image, nothing analyses a film better than another film.” In Cote’s work, the archival and original speak from two distinct moments but across a shared landscape, permitting both historical distance and connection. No attempt is made to overtly narrativise the connection between the two; the found footage is altered through reconfiguration rather than technical intervention. The result is a quiet consideration of the continuities and discontinuities of place and what it might mean, through the vehicle of analogue film, to travel through it, physically and cinematically.

Image courtesy Harkat Studios.

If Cote’s work inaugurates a reflection on the temporal and geographic flexibility of the analogue, the festival’s closing act, charmingly titled “It Ends with a Kiss,” demonstrates its democratic potential. A “tender roundup” of “homegrown films on film,” it includes films produced at the studio’s residency, by the attendees of the festival workshop, as entries for the Straight 8 film competition, and the winners of Harkat’s own ek-minute (one-minute) competition, where filmmakers sent in scripts and selected entries were given film stock to produce them on. In the now seminal essay, “For an imperfect cinema,” Cuban filmmaker Julio García Espinosa advocates for a cinema that is “no longer interested in predetermined taste,” capable of being created “equally well with a Mitchell or with an 8mm camera, in a studio or in a guerrilla camp in the middle of the jungle.” “It Ends with a Kiss” approaches the analogue with a similar embrace of amateurism and experimentation, making space for film as process; concerned with craft but also with collective labour and expression. The films in this section of the programme range from the personal to the absurd: collaborative meditations on girlhood sitting alongside macabre silent films and experimental engagements with landscape. Addressing this sense of openness, Talwar describes Harkat as a “kind of cinematic third space,” dedicated to enabling an “audience of anyone” to build an imagination of cinema outside the mainstream.

Image courtesy Harkat Studios.

Within the persistent cinematic legacy of Mumbai, both the incongruence and value of an effort like Harkat are evident. Talwar speaks of the studio (after critic Kim Knowles) as a “site of photo-chemical resistance,” made political by its “intimate existence in the heart of a hyper-commercial film industry.” The decade of care that has gone into sustaining this space is visible in the breadth of its curation, in its openness to new entrants, and in its ability, over three days of thoughtful programming, to provide a glimpse into alternative cinematic futures. For Mumbai’s filmmakers, and for its audiences, the 16mm Film Festival is an unlikely and special space, an example of what it might look like, in Talwar’s words, not just to create cinema, but “to make consciously, and with love and understanding.”

Image courtesy Harkat Studios.

To learn more about analogue lens-based practices and collectives, read Ankan Kazi’s essay on Ayisha Abraham’s found footage films, watch Najrin Islam’s conversation with Srinivas Kuruganti on his work with The Analogue Approach Project and revisit Anisha Baid’s curated albums from Jagadish Upadhya’s Film Foundry and Rupesh Man Singh’s collaged photographs.