"Listening to the Whispers": On Memory and Cyclical Time in Arpan Mukherjee’s “Impermanence”

“He went back…to climb the mulberry tree in the courtyard of the old house and catch the moon that did not fall into the well.”

—Mahmoud Darwish, transl. Ibrahim Muhawi,

Journal of an Ordinary Grief (1973, 2010)

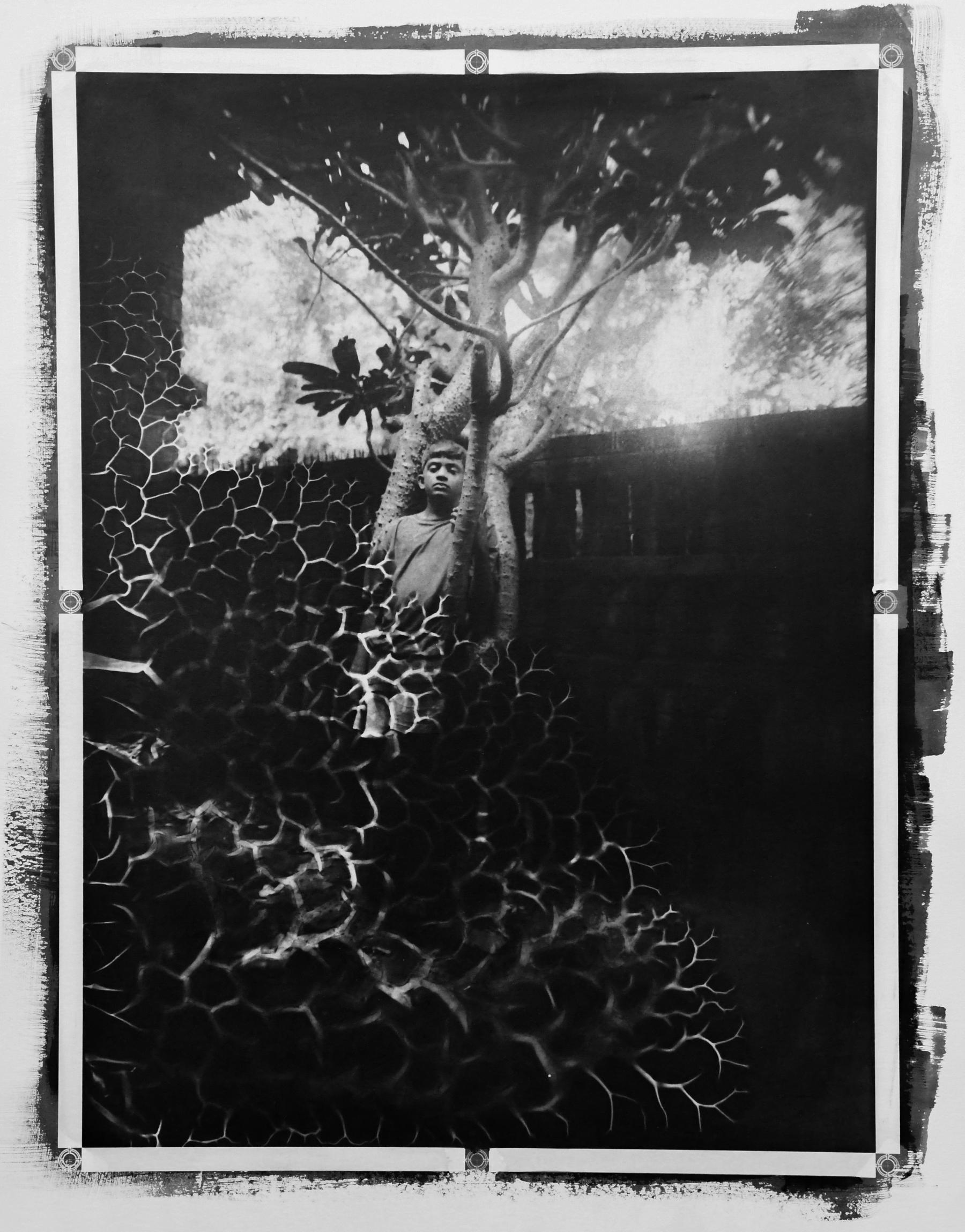

From the series Gola Vora Dhan. (2015–24. Gum Bichromate Print on Paper, 30 x 22 inches.)

In his introspective exhibition Impermanence, which was on view at Cymroza Art Gallery, Mumbai from 14 February–15 March 2025, Arpan Mukherjee confronts his own experience of rural-urban migration from Adityapur to Bolpur in Birbhum district of West Bengal in the 1980s as a lens through which to tell the tale of socio-cultural changes in post-independent India’s rural spaces.

As discussed in the first part of this essay, IR36, the 1 hour, 7-minute video installation accompanied by sound recordings of Mukherjee’s interviews with former residents of the village he grew up in—Adityapur—is a mournful story of loss. In the remaining three bodies of his work—Gola Vora Dhan (2015–24), Journey to the Himalaya (2022) and The Dew Drops (2019–25)—Mukherjee probes the idea of circular time as he returns and keeps returning to the place of his childhood.

From the series Gola Vora Dhan. (2015–24. Gum Bichromate Print on Paper, 30 x 22 inches.)

In Gola Vora Dhan, a long-term exploration of the uprooting experience in Bengal in the 1980s, Mukherjee bears witness to the abandonment of Adityapur, the place he left as a child. What started out as a project to document empty spaces—both courtyards that were once teeming with members of joint families and public spaces that were used to discuss village concerns—has taken on allegorical form.

We see members of his immediate family in a deteriorating landscape that he once inhabited but which remains foreign to them. This feeling of dissociation between subject and environment lends the images a near-spectral quality and is doubled down by the performative aspect foregrounded by the manner in which Mukherjee places his family members in front of the camera. The artist emphasises: “I use the word performance deliberately. The shutter speed was long, so the moving image will vanish, just like the tourists.” His work offers a powerful commentary on the seeming imperative of rural-urban migration and the ephemeral presence of people in the village of his origin. Moreover, by turning those most intimate to him into symbols of disappearance, he gently nudges us to contemplate the fragile meanings of home and belonging.

From the series The Dew Drops. (2019–25. Carbon Print on Paper, 15.3 x 11.2 inches.)

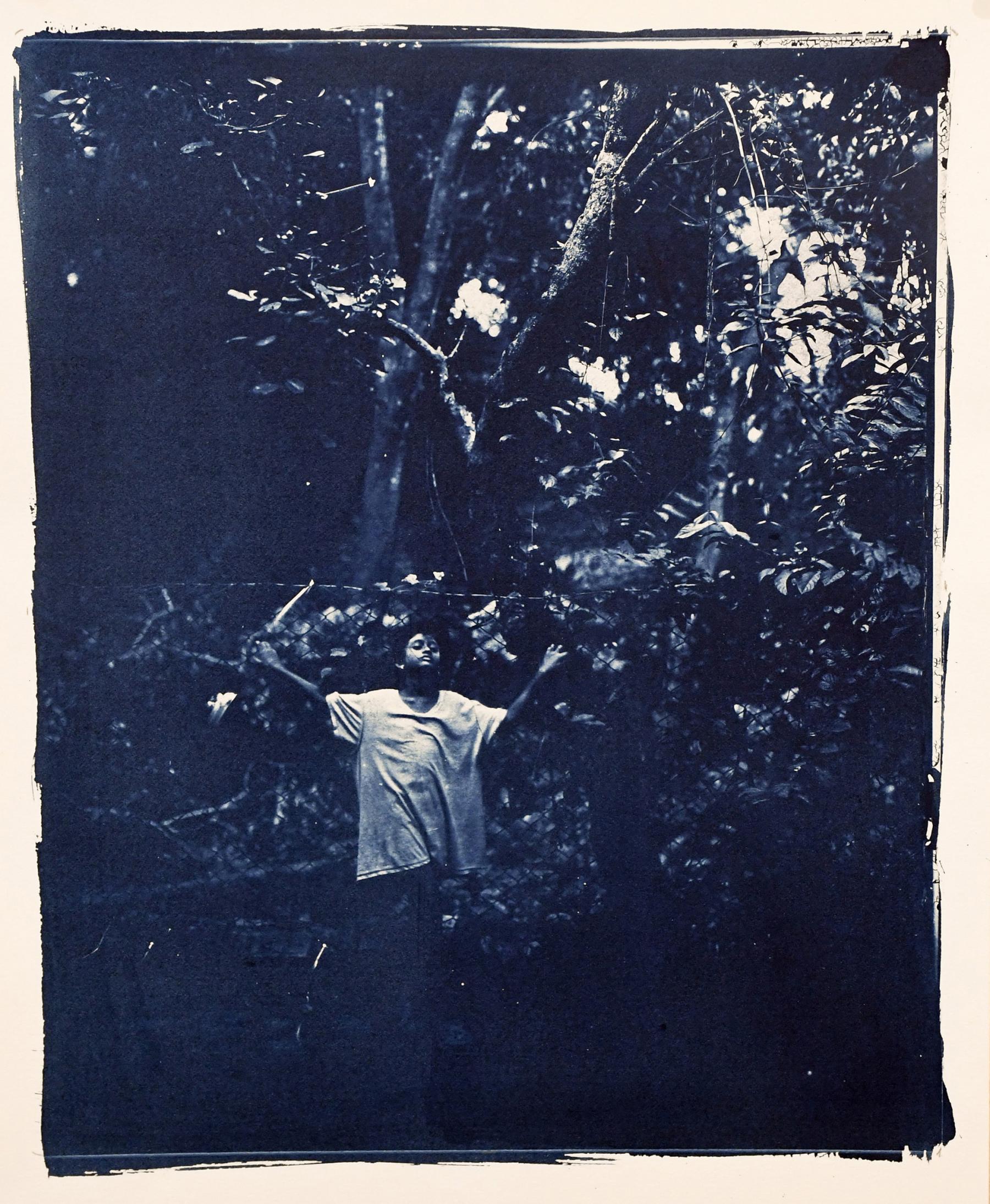

In a series of paradoxical works that hold multiple layers of meaning, Mukherjee explores the relationship between permanence and impermanence, as he explains in this artist video, through play with the contradictions between material and their photo-sensitivity, and actual life as it is lived. If his subject is the mundane—sustained through an everyday practice of taking images—it is in the process of photo-making that he is trying to make the familiar unfamiliar, he argues.

Thus, his photographs in The Dew Drops are a soft meditation on the various hues of intimacy that fill the vessel of life with nourishing presence, even as transience is always already inscribed in the fleeting nature of time. Mukherjee explores this contradiction by employing carbon print—a very long, time-consuming printmaking process that produces "permanent" images since it uses pigmented gelatin rather than silver or other metallic particles that are prone to deterioration over time. Developed in the mid-nineteenth century as a response to fading in silver-based prints, the name itself derives from the initial use of carbon black as the pigment; however, the printmaking process allows for the use of any pigment. Mukherjee's choice of pigment, he says, was lampblack made from soot, which utilises carbon, "the basic, fundamental unit of life." Thus, by using carbon printing, which involves several elements of uncertainty even as it becomes a means to preserve tonalities of the negative without any loss and protect against degradation of the photograph over time, Mukherjee highlights a juxtaposition between the creation of an enduring record of time as captured in the image and the impossibility of “fixing” a moment, evasive in its very essence. We are forced then, through Mukherjee’s lens, to sit uncomfortably between a quiet contemplation of the fragility of mortal life in its finitude and a treasure trove of cherished memory. His works thus serve also as an invocation to be present in the moment.

From the series The Dew Drops. (2019–25. Chlorophyll Print on Cauliflower Leaf from Kitchen Garden, 5.5 x 10 inches.)

The transitory essence of life and of the reality of beauty and decay as fundamental to human existence is further explored in his engagement with his neighbours. Photographing the deserted well in his neighbour’s empty courtyard, a remnant of Santiniketan architecture at an earlier point in time and no longer in use, he is interested in seeing things that may no longer seem significant and tracing how they have changed over time.

This is not merely a document of time past, however; it is a gesture of warmth and focus on community that repeatedly features as a primary concern in Mukherjee’s work. He picks up a family album abandoned in his neighbour’s home and prints images from this found album on collected ceramic tiles and cauliflower leaves from his kitchen garden. “I used to share cauliflowers with my neighbour,” he says, and while this print will deteriorate—it is not meant to last—it becomes a remembrance of the pleasures of the humdrum and the relationship the neighbours once shared.

From the series Journey to the Himalaya. (2022. Gold-toned Salt Print on Paper, 4.7 x 12.6 inches.)

Similarly, characteristic of Mukherjee’s use of metaphor, the images in Journey to the Himalaya, are not only about a family holiday to the mountains. Rather, Mukherjee employs one of the earliest photographic printmaking techniques—salt prints—which were used in nineteenth-century colonial ethnography and anthropological documentation toward control and conquest. In the context of Mukherjee’s emphasis on the materiality of the image-making process in his exploration of migration and loss, one cannot help but think of Mumbai's salt pans that have been proposed as sites to rehabilitate a proportion of the one million residents of Dharavi—the world’s largest slum—in the Adani-controlled redevelopment project that is feared to have lasting consequences on displacement and livelihood, even as absurd plans to build homes on salt pans will bode disaster for salt workers and the ecological imbalance of the city, where this exhibition was held.

In Mukherjee’s hands, however, the photographic printmaking process of salt prints transforms from its centrality in colonisation to a sobering exploration of time and memory. Noticing degradation of the negative with time, the imprints of which are visible on the salt prints, Mukherjee began unconsciously experimenting with the process of decay and memorialisation within a non-linear conception of time. By printing the same set of images over regular intervals, the deteriorating negatives permitted him to "trace back time in between," he says, and explore the idea of growing, of evolving and of impermanence. For him, he elaborates, the images are a way “to cherish memory and explore how memory travels to them; and how they decay is an interruption of time.” Emphasising the notion of “fluid time” and “time as circular,” he says his process is not always logical; sometimes he does not know what he is doing, but trusts that “the image will figure it out.”

From the series Gola Vora Dhan. (2015–24. Gum Bichromate Print on Paper, 30 x 22 inches.)

As Mukherjee stated in a recent talk at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), titled “Listening to the Whispers,” the final photograph is then not only a memory of the fleeting moment it captures, but also “the memory of the process of engagement.” If he describes listening as a key and active component of his practice, this is not only to hear the lament of loss but also in search of the potentialities for renewal. Thus, even as he mourns the discourse around agricultural work that uses “chasa” (farmer) as a derogatory term and reflects on the process of decolonisation and the ways in which the failures of post-Left governments in Bengal forged the path for religious fundamentalism, his practice is not limited to critique or documentation. Rather, his work is nourished by dreams of a return to the cultivation of land.

This impetus toward a gradual process of renewal is reflected in the process of gum bichromate printing he utilises for Gola Vora Dhan. If the charcoal powder mixed with a powder pigment in colour allows for the rough texture of the surface, lending a near-physical quality to these large, full-size images, he says the magic one encounters is not on view: it occurs in a series of repetitions while making the gum bichromate prints. The dichromated gum and solution is placed in contact with the negative and exposed to UV light, creating a hardened gum layer. After exposure, this layer is developed in water and the image appears from the black surface. However, this is not the final image, and it is here that the wonder lies; Mukherjee repeats this process two-three times and is able to witness the different degree of tonalities that emerge with every repetition. For instance, in the first sensitisation, only fifty to sixty per cent of the final image may be seen, with more intricate tones appearing with each repetition, thus permitting multiple sites for exploration.

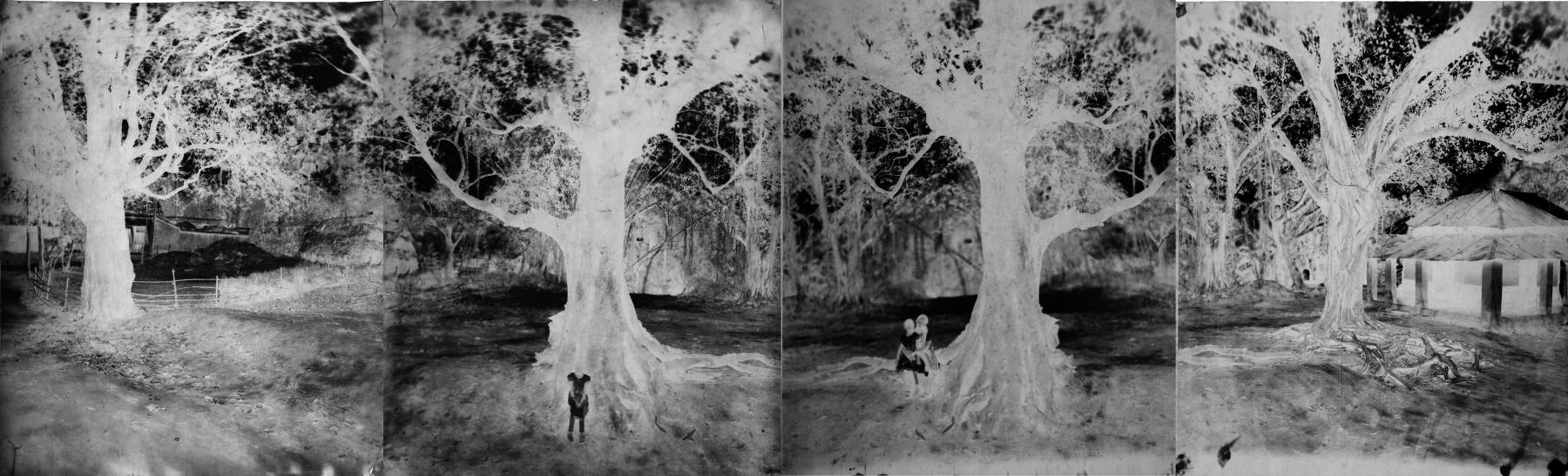

From the series Gola Vora Dhan. (2015–24. Calotype Paper Negative [four negatives stitched], 12 x 40 inches.)

Not a believer of linear time, Mukherjee expresses how “time has a certain fluidity and allows one to travel almost…The same point comes back again and again,” he suggests. “While it is never exactly the same but something else, there is the possibility of growth and change.” Similarly, he articulates a notion of circularity in the structure of migration, too, as reflected in the title he gives to his long-term work: Gola Vora Dhan translates into a storage filled with paddy, and it is this “wish and desire,” he emphatically says, which forms the “fuel” and “vital part of his energy in making work.”

The idea of return then is a looming presence in Mukherjee’s work and life; one was expected to get a job in the city and did not have the confidence to cultivate, he shares. But he has purchased land in his village and begun to grow paddy. Even though he is not doing it in the same way as his grandfather, there is a certain back and forth of time, marked by an embrace of the circularity of life, itself largely influenced by the Santiniketan ethos. In stark opposition to linearity, which forces competition with one’s own self, here, “in Santiniketan,” Mukherjee deliberates, “the primary way of life is that time is not rushed; it is unhurried.” Seamlessly traversing between the material and the natural, Mukherjee’s practice is an invitation to remember that pleasure is to be found in the process of living; for, as he narrates in his matter-of-fact yet lyrical manner, “spring will come again.”

From the series Gola Vora Dhan. (2015–24. Cyanotype from Glass Plate Collodion Negative on Paper, 15 x 11 inches.)

In case you missed the first part of this essay, read it here.

To learn more about artists working with analogue printing techniques, read Hitanshi Chopra’s review of the exhibition Being in a State of Salax (2021) and Saloni Jaiwal’s review of the exhibition Dreams of a Summer Past (2023).

All works from the exhibition Impermanence (2025) by Arpan Mukherjee. Images courtesy of the artist.