On Process at the Chennai Photo Biennale

From the series Faces of Expression. (Image courtesy of Priyanka Oberoi.)

Animated by the question ‘Why Photograph?’, the fourth edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale draws attention to the histories and fundamentals of the photographic process. Arun Karthick’s Apocalypse: A Love Story uses 8mm film to engage with ancient Jain ruins. Standing Still features pinhole camera-produced photographs composed at a workshop organised by Michelle Loukidis, representing the Johannesburg-based Through The Lens Collective (TTL), in collaboration with Timbuktu in the Valley. Standing Still is part of the youth-focused curation ‘What Makes Me Click!’, which also includes Faces of Expression and Familiarity of the Unknown. Guided by Priyanka Oberoi at NCR’s Prakriti School, the six contributors to Faces of Expression shot black-and-white portraits and then intervened on their surfaces by hand, a reference to the intermedial legacy of photography. Nilanjana Nandy was among the mentors at NCR’s Nirmal Bhartia School whose students composed photographs for Familiarity of the Unknown, themed around the architectural form of windows and invoking the camera aperture itself as one. Celebrating fashion house Raw Mango’s fifteenth year, Adityan Melekalam, founder of design studio Squadron 14, curated Common Nouns, which featured fifteen artists reinterpreting traditional South Asian heritage, including textiles and scripts, through contemporary technologies such as digital and generative tools.

Kamayani Sharma (KS): Priyanka, Nilanjana and Michelle, you are all involved in art education geared at young learners. In the context of teaching creative practice in an age of speed, can you talk about how your pedagogical approach engages with the principle of slowness?

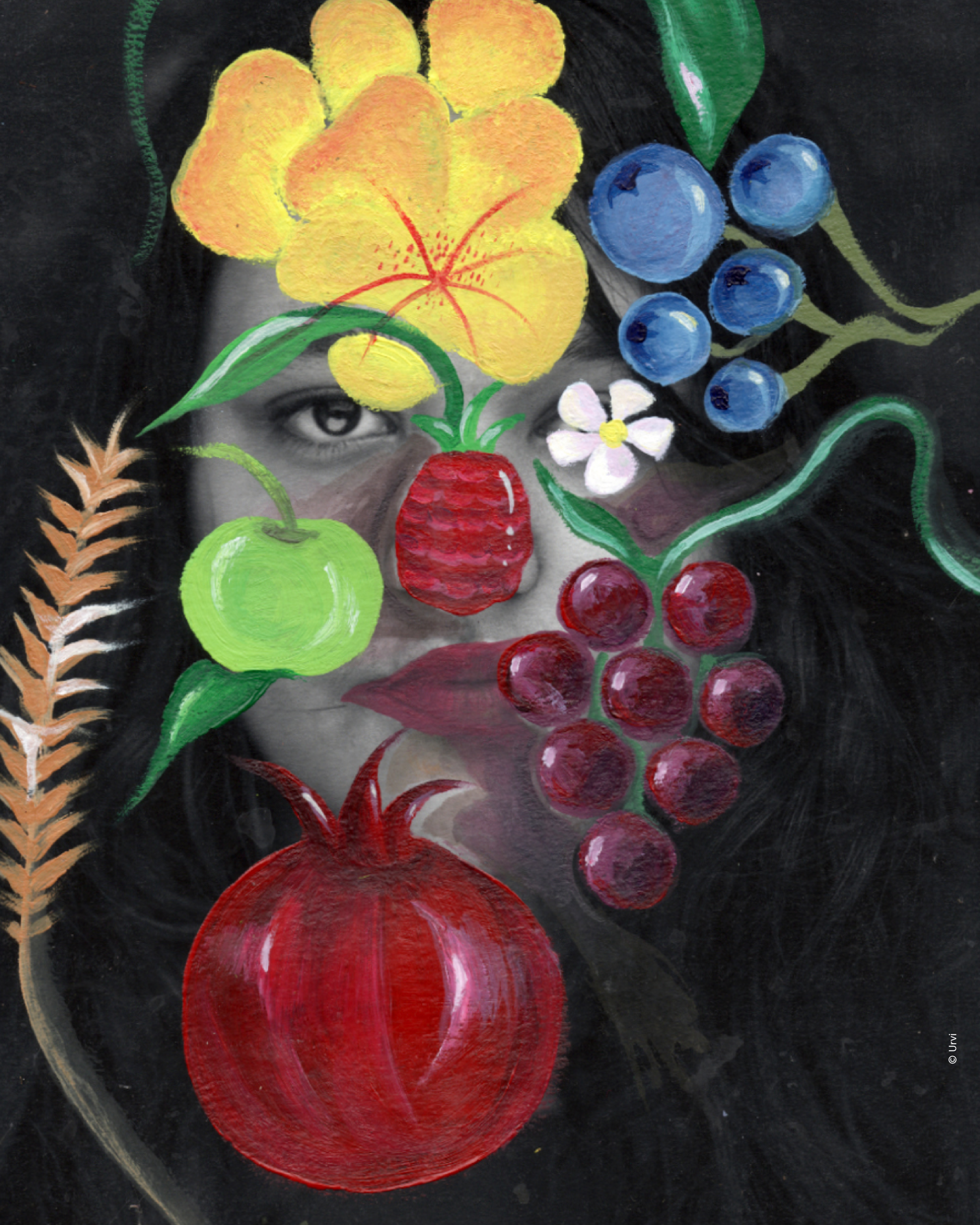

From the series Faces of Expression. (Image courtesy of Priyanka Oberoi.)

Priyanka Oberoi: When we saw the open call, ‘What Makes Me Click?’, the six participants decided that the theme would be portrayed through the same set of portraits. For the photo shoot, we decided not to use fancy studios or lights and just used natural light. We used a piece of tin as a reflector, took pictures, edited them on Photoshop and finally got three portraits that we were happy with. Each one of the six participants took those three photographs and gave their own take on ‘What makes me click?’

I know a lot of the students were not very happy about doing the project on paper (we used museum etching). I explained that this is how you slow down. There are a lot of small things you learn when you slow down and take pains to make each line. You are much more aware of what you are doing. Control C, Control Z, no…when there is a mistake, there is a mistake. Things can go wrong, and then you have to repair it. How do you repair it? There is no option to undo, and then it becomes kind of interesting.

One participant surveyed the drinks everyone liked and was interested in showing that visually. Now, every drink has a different pH value, so he went to the chemistry lab and tested the pH of various drinks using strips. Every pH value gives a different colour, and he incorporated those pH tests into his portraits. We made a pH solution to dip the photographs, but it did not work. So he emulated the look and feel of a pH strip by painting over the portraits with normal inks because he still wanted translucency. Another biology student, interested in the intricacies of the body, chose to strip the skin off and see what lay beneath. She did a lot of anatomy research, and exposed the actual musculoskeletal structure using colour pencils.

From the series Faces of Expression. (Image courtesy of Priyanka Oberoi.)

One student interested in post-apocalyptic worlds and video games created his art digitally first, going on an app where you can select elements like helmets to build video games. Then when we tried to put the helmet on the portrait, it would not fit. So then he just altered them physically on paper. A fourth student worked on the idea of a split personality by first digitally manipulating the pictures together. On the printout, she used the process of stippling to create the effect of split personalities on the portraits. Another participant who really likes anime did a study on why Japanese cartoons have exaggerated emotions and used pen and acrylics to superimpose similarly exaggerated emotions on the pictures. And finally, one student who was really impressed by medieval Italian painter Guiseppe Arcimboldo’s “Vertumnus” made her work in a similarly extravagant manner using acrylics and inks.

From the series Familiarity of the Unknown.

Nilanjana Nandy: This project was part of an inter-school programme called ‘Voice of Art.’ This edition explored how the window can become an identity. We first clicked windows in the school, whatever they felt was architecturally interesting. Our school is in Dwarka, which predominantly consists of apartments. So, one of the art educators took the four participating students on an observation tour of apartments near the school. They continued this practice in their own respective neighbourhoods. Also, in the course of discussion, we made them aware that when you are looking at somebody's window, you have to be mindful about their presence. How do you take decisions in a way that the person behind the window, even if not in the frame, will be okay with? So, with their immediate neighbours, they, of course, took permission and then clicked.

From the series Familiarity of the Unknown.

When it comes to photography as a technique… nowadays, children click all the time because the mobile is in their pockets. We tried building on that accessibility, and we first went with props—the viewfinder, let's say a window cutout. So if you cut out a paper frame and see through it, then what is an interesting composition? We showed them how buildings are shot. They googled monuments to see how they are photographed and how light and shade play there. We have gone more from the point of view of the different elements of an image and how just by using this mobile camera, you will get the best image. For some time, we did not use any filters and we did not crop the images. We wanted to see what the children saw through that viewfinder. The moment they have a mobile in their hands, there is no stopping the cropping, the filters, the panorama, but that is why I brought in the window cutout first. You just see what is an interesting view; now only observe light. So in a way, while executing, we were trying to slow them down a little.

From the series Standing Still.

Michelle Loukidis: The changes in the directions that photography has taken here are dramatic. So with younger people, I thought it would be a good idea to actually introduce the notion of the magic of photography. The digital age has removed some of the magic. The easiest and the most obvious thing was to make pinhole cameras. And it is quite a hands-on process because children can also make their own cameras. It is just this desire to make people slow down a little bit and consider what light does and how photography works. And also in the age that we live in now, there is this thing of also not getting success the first time around. Because you can go out with the pinhole camera and photograph a couple of times, and it does not work. So you have to think about what you are doing and readjust things, and this is another part of slowing down. You have to go into the dark room and then reload your paper. You have to go back outside, find another spot, wait a couple of minutes for your exposure, and then come back in and process. You can do it as fast as you would like, but it does not matter. It still is going to slow you down. You still have to sit still in front of your little camera. And there is an incredible playfulness as well because you do not know what you are going to get.

The area where TTL is located is not a very affluent neighbourhood, so the idea of going into a dark room was quite astounding for them. We explained to them the magic of the camera obscura and worked with this idea that you are making your own camera, first of all, and then you are putting in a blank piece of paper in the dark into a camera and then going outside and positioning it vaguely in front of the thing that you want to photograph. We also thought a lot about what they could photograph; it was a funny idea to do selfies in a weird way. We had to explain that idea of stillness. We actually have to stand still and be still for a couple of minutes. And the fun part is when people do move, there is obviously the blur, but sometimes they are moving so much that they just disappear, which really intrigued the children as well.

Still from Apocalypse: A Love Story by Arun Karthick.

KS: Arun and Adityan, can you talk about how your creative and curatorial approaches engaged with the idea of histories of media and materials?

Arun Karthick: History, pre-history and the idea of new narratives emerging upon excavating layers of ground beneath us continue to fascinate me. I do not wish to subscribe to the existing notions of published history told by the systems of oppression. Myths, symbols and mysteries often seem more sane and revealing than the larger totalitarian society we are part of. It is only through creating images, sounds or experiences that we get to access that aspect of our consciousness. Frankly speaking, I was going through a break-up and wanted to express it through the ruins I found scattered in an ancient Jaina land!

Still from Apocalypse: A Love Story by Arun Karthick.

The small gauge film which commonly refers to the small formats 8 mm, Super 8 mm and 16 mm has a fairly simple entry process of learning the camera/techniques to get initiated to celluloid. The tonal quality of light and darkness, the textural tactility and the often imperfect, grainy-looking images such small formats produce can aid in creating specific feelings. I like a sense of mystery in the image—parts of it left to our minds to complete. Also, one gets to work on closer focal lengths with small formats, so one learns to connect themes through tele-images.

Still from Apocalypse: A Love Story by Arun Karthick.

I adapted to the process of ‘Straight 8’ style which mandates that you only shoot with one roll of colour negative Super 8 mm film cartridge. Its maximum length is about 3 minutes 15 seconds. Everything about your film can only be made in-camera on that one cartridge. You plan every shot and its duration carefully to shoot it only once in sequence without retakes, for an in-camera edit sequence. No editing is allowed or performed later. The soundtrack was 'blind' as you would not have seen your film. You will have to imagine or remember what you exposed on the roll, write a voiceover or music for it, and the Straight 8 community will develop/scan and marry the sound with video. Only then do you get an actual preview of your images with the blind soundtrack ‘married’ together. The experience of discovering this union and sometimes the disunion of rhythms/ideas is truly unique!

Installation view of Common Nouns at the Chennai Photo Biennale.

Adityan Melekalam: Over the past twelve years, we have had the opportunity to closely observe Raw Mango’s ability to connect the contemporary with the traditional—not just through its designs, but also through its spaces and collection of objects. As Raw Mango approached its fifteenth anniversary, we felt it was the right time to reflect on its journey as a cultural participant and observer—more than just a design house—constantly questioning and understanding the societal systems and values that shape us. Common Nouns became a way to explore these ideas through a forward-looking lens, reinterpreting Raw Mango’s principles in ways that resonate with today’s visual and cultural landscapes.

The focus was on understanding material cultures as carriers of histories and ideas while probing their transformation across time, inspired by anthropologist Igor Kopytoff’s notion of approaching objects as biographies. Our conversations with the artists revolved around exploring how traditional materials and symbols could be reimagined through contemporary tools and expressions—while some artists reflected on materiality itself, others speculated on language, symbols and motifs. We approached the resulting diversity of practices and ideas by focusing on shared themes and examining how these evolve across geographies and generations. The arrangement of the works was intended to enable a layered exploration of our belief systems, which assign value and meaning to the things around us.

Installation view of Common Nouns at the Chennai Photo Biennale.

To learn more about the fourth edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, read Mallika Visvanathan’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore memory and with the curators of the primary shows, Vishal George’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore urban landscapes and with artists whose practices explore the theme of labour, Anoushka Antonnette Mathews' short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of mental health and neurodivergence and with artists whose practices explore themes of bodies and landscapes, Upasana Das’ short interviews with artists and practitioners exploring forms of community building and with artists whose practices explore themes of power and representation as well as Kshiraja’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of landscape and history and with artists whose practices explore themes of myth, ritual and identity.

All images are courtesy of the Chennai Photo Biennale, unless mentioned otherwise.