Pink Revolution: Nishtha Jain's Gulabi Gang

This Women’s Day, Bangalore International Centre organised a screening of Nishtha Jain’s 2014 film Gulabi Gang. Amidst the ongoing ‘celebrations’ and many shades of pink on display, Gulabi Gang stands as a stark reminder of the inequalities that exist not only between men and women on the basis of gender but also between women themselves, given the vast differentials in socio-economic realities, i.e., between rural and urban, upper caste and Dalit-Bahujan, Hindu and Muslim and so on. Despite having been produced over a decade ago, Gulabi Gang still holds relevance in the context of increasing violence and injustice against women.

The 96-minute documentary follows Sampat Pal, the founder of the Gulabi Gang, and her group of women vigilantes fighting patriarchy and caste oppression in parts of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh in India. Refusing to stand as mute spectators to the injustices around them, the women collectivise as a means to survive the system and in doing so, create a space for solidarity and support. We see the gang in action, fighting family members, villagers, police authorities, government authorities, etc. The group works relentlessly, seeking justice for women and young girls who have been unjustly murdered, fighting for land rights or participating in Panchayat elections.

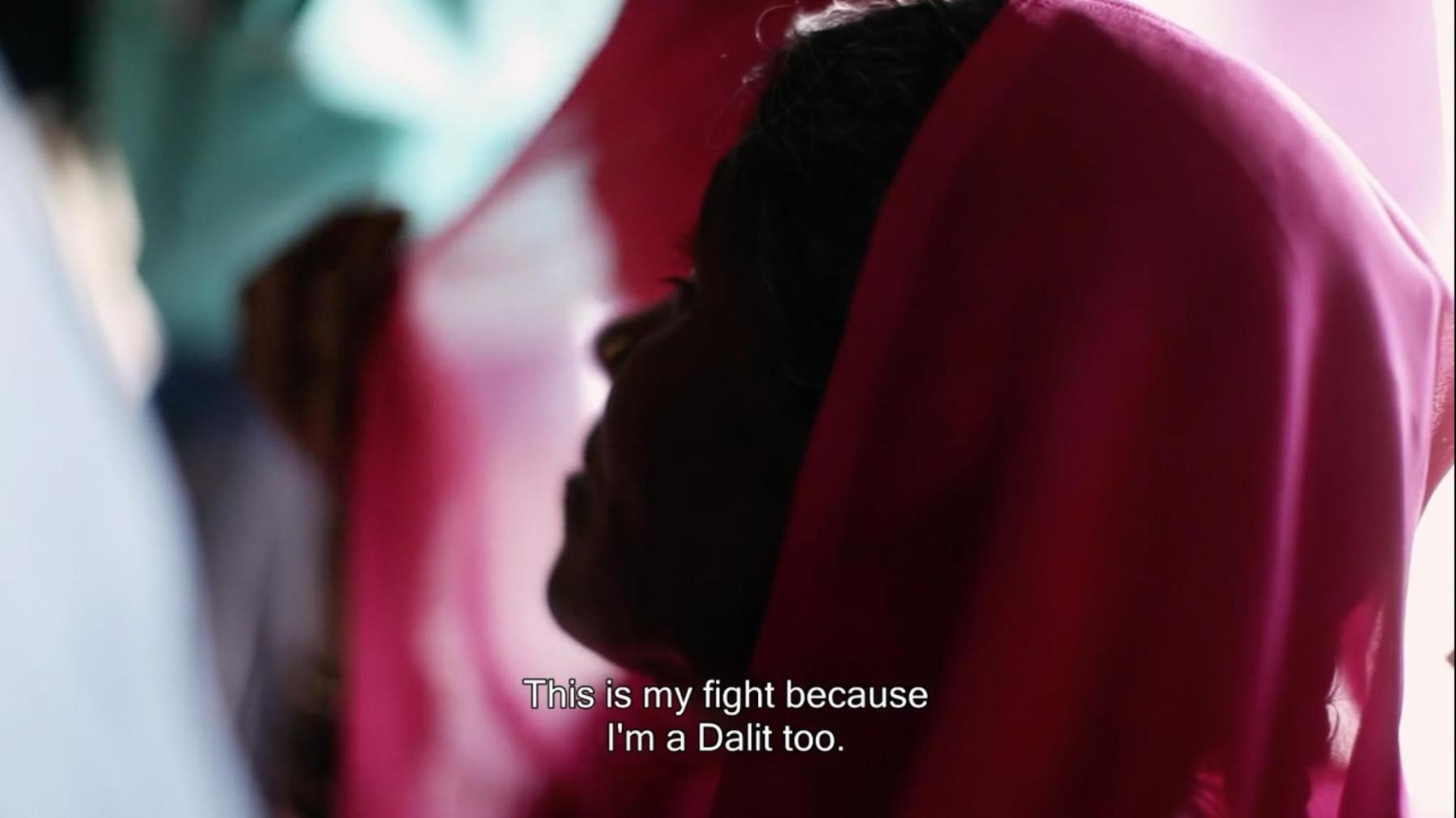

The film begins with shots of women in pink saris, their heads covered and their hands bearing lathis (wooden sticks). We cannot clearly see their veiled faces, but we can see the lines on their palms that betray struggle and the cracks on their feet from years of invisible labour. We can hear their voices, “This is my fight because I am a Dalit too.”

The film interweaves multiple poignant moments as it journeys through layered realities. While the shot taking is raw and attempts to capture reality as closely as possible, the editing is stylised without being sensational and reflects the many complexities that the film attempts to unpack. The storytelling is elevated by the long, journalistic style shots that allow audiences to feel like witnesses to these moments of injustice and violence. Jain shares, “I love working with Rakesh Haridas (cinematographer of Gulabi Gang). He writes with the camera. He works quietly, gently, respectfully, almost melting into the scene. What he brings to the film is invaluable. Each one of his shots tells a story and is complete by itself.”

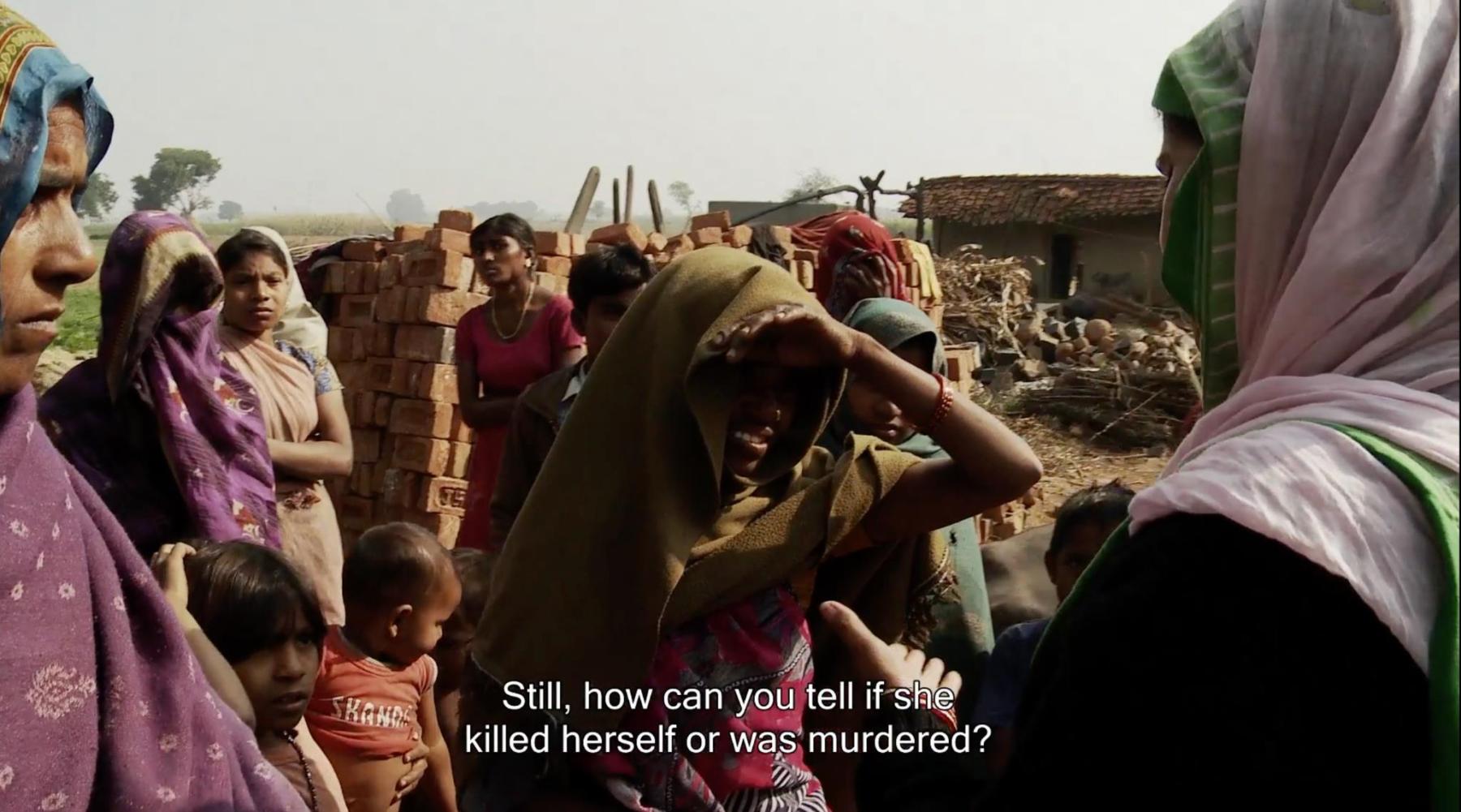

The film exposes us to the reality of the girls whose murders and deaths are covered up, not only by their husbands and in-laws but also by their own parents. The ill fate of the girl is repeatedly invoked as the underlying reason for death.

In one scene, Sampat enters Sangrampur village, where a girl has been found burnt to death. The family leads Sampat to the kitchen, where the girl's body lies, untouched and charred beyond recognition. The family and husband try to convince Sampat that she was burnt to death, yet on closer inspection, Sampat finds the site manipulated by the family members. Others in the village too shout slogans against the Gulabi Gang.

The crew follows Sampat almost in real time and pans to the body of the girl, who lies with her legs spread apart. Jain chooses to keep the disturbing visual of the deceased. On being questioned on this choice, she responds,

“It was shocking and unbelievable that we could just walk into a room with a charred dead body lying on the floor. The villagers were going in and out, even children. There was little respect for the dead girl or fear of the law. The family had dressed up the scene and thought Sampat Pal would help them pass off the scene as suicide. We, of course, will never know what would have happened had the camera not been there. We debated over taking the shot of the dead body during the shoot and later while editing it. I decided to keep the shot because I wanted to share the raw reality, to reflect the sheer banality of violence in these parts.”

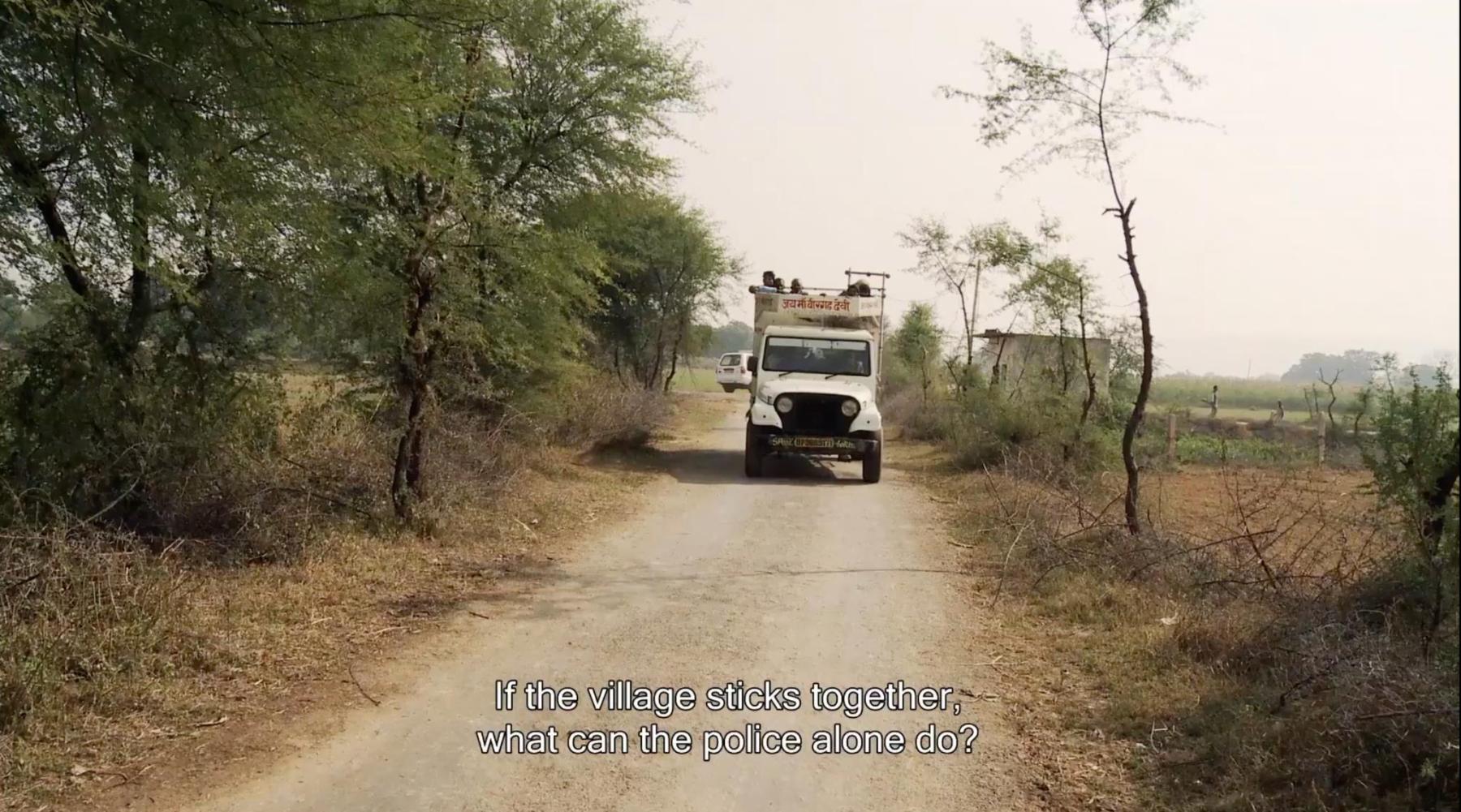

The crew encounters the father and uncle of the deceased on the road that runs beside a field. They are quite obviously intoxicated and not very coherent. Sampat confronts them and makes a desperate attempt to push them into admitting the truth, but they seem to have no interest in pursuing the case further. The camera pans to the field nearby, revealing spectators that have been watching silently on the margins. As the camera stays on them, both parties continue to look at each other. The men start exiting the frame until all we see is the empty field, poetically capturing the discomfort of the spectator who remains mute out of fear, out of disinterest or out of resignation to ‘fate.’

Jain recalls how,

“Both men and women were spectators to the violence. And that is what Rakesh has captured through the shot. When the men become aware that the camera is now focused on them rather than the family of the dead girl, they feel uncomfortable and start to leave the scene one by one. This was not a planned shot. What was great was that Rakesh Haridas kept the camera rolling till the last man left the scene. My editor had not kept the entire length of the shot, but it was my favourite shot, and I decided to keep the whole length of the shot during the edit.”

The film also captures moments where Sampat is alone, against the backdrop of a setting sun, in the field or at the pond. She walks to the pond, bends down and washes her hands and face, almost in anticipation of the sequence that is to unfold where one of the gang members will be cut loose.

Jain shares, “In the film we only see a sobered-down version of reality. There was more drama in real life. They say real life is stranger than fiction and it is really true for most of my films. The films are only small glimpses of the complexities of reality.”

To learn more about Nishtha Jain’s work, read Kshiraja’s review of Farming the Revolution (2024) and watch the episode of In Person in which Jain talks about The Golden Thread (2022).

To learn more about films exploring how women navigate patriarchal society, read Sucheta Chakraborty’s review of Jayant Somalkar’s Sthal (2023) and Ria De and Koonal Duggal’s reflections on Payal Kapadia’s All We Image As Light (2024).

All images are stills from Gulabi Gang (2014) by Nishtha Jain. Images courtesy of the artist.