On All We Imagine as Light: Caste Hindu Endogamy and the Possibilities of Love

Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light (AWIAL) (2024) is about the lives of three migrant women nurses and the ways in which they form community and solidarity with each other in the backdrop of the city life of Mumbai. It engages the politics of love and caste endogamy and that of migrant labour, as well as who can be a state and city subject and who cannot.

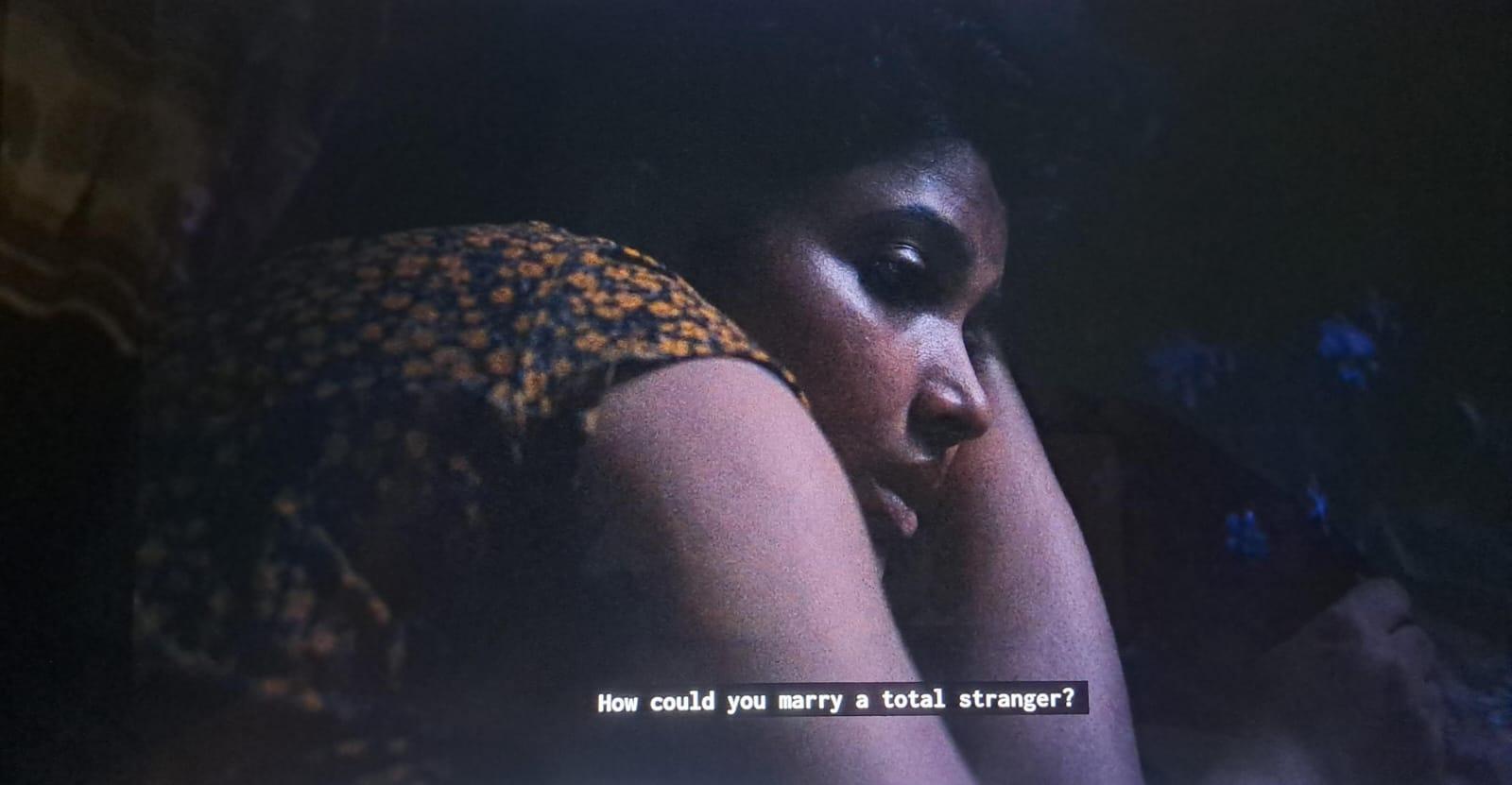

Anu wondering about Prabha's story of how she got married.

In his seminal text, “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development” (1916), Dr B.R. Ambedkar argued that the purity of caste is preserved through endogamy or the marriage of a man and a woman belonging to the same caste. By discouraging intermixing, caste Hindu endogamy protects women’s bodies and sexuality as property to maintain the territorial integrity and purity of the particular caste community. Turned into surplus women, unmarried/widowed women are, Dr Ambedkar contended, an explicit threat to the structures of caste since there is an increased likelihood of them claiming agency over their bodies and sexuality. Historically, sati, enforced widowhood and child marriage regulated these surplus women lest they marry outside their caste and pollute its hierarchy.

Parvaty ruminating about what it takes to be real in today's world.

AWIAL shows what it might mean to be surplus women in today’s India and how love can be experienced outside caste Hindu endogamy. It could mean being like Anu (Divya Prabha) and Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam), who want to live life on their own terms. The shadow of displacement, a dead husband, age and poverty have pushed Parvaty to a life of precarity. She refuses to give in to the historical predicament of Hindu widows—to become reliant on the care of sons and/or well-meaning friends and relatives. In a scene where Prabha (Kani Kusruti Kanmani) is helping Parvaty look for identification papers, she asks: “Why not move in with your son?” Parvaty replies: “No, no. He already lives in a tiny room with his wife and kid. I don’t want anyone breathing down my neck. We are the same, you and I. We are better off alone.” Later, she turns down Prabha’s invitation to move in with her and Anu. Today, a surplus woman might even look like Anu, who can fully claim her sexual and bodily agency in her interfaith relationship with a young Muslim man, Shiaz (Hridhu Haroon). In contrast to both these women, Prabha exists as if on a precipice, where she holds the tension between two opposing drives—the norms of a given community and the porousness of a chosen one.

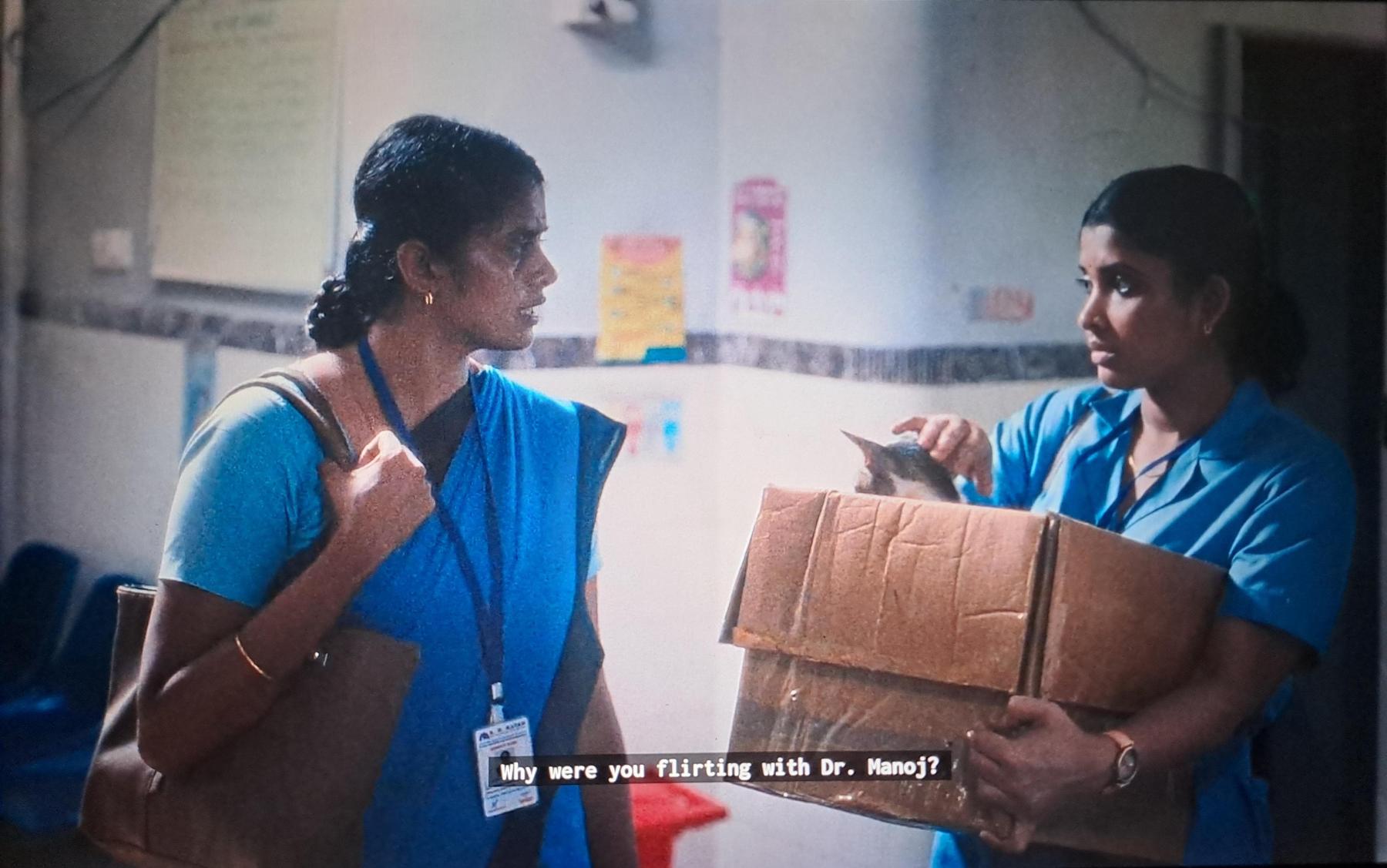

Prabha telling off Anu for flirting with the doctor.

On the one hand, Prabha embodies the neurosis caused by caste Hindu endogamy, where the caste community or the given community precedes individual desire and love. The shadow of this community lurks around in the quiet longing for her absent husband and in the ways she herself enacts the norms of caste Hindu purity and virtue as she relentlessly polices Anu and herself. Prabha walks away from her colleague Dr Manoj’s (Azees Nedumangad) romantic overtures after engaging with them for a while even as she slut-shames Anu for “flirting” with him. She tells Anu: “No one will respect you if you behave like a slut.”

Parvaty and Prabha's shared world of absent husbands.

Restricted by normative gender and professional roles, she is only able to see sexual undertones in Anu’s playful conversation with a fellow Malayalee man (the doctor). Prabha shifts between her jealousy given the history of her own feelings for the doctor, the unease of her morality, and the awareness of the hurt that it causes to Anu. She apologises to Anu soon after, but her anger returns when she finds Shiaz and Anu being intimate in Parvaty’s village. She wants to immediately go back to the city, potentially upsetting Anu’s plans of spending time with her lover. Perhaps her anger and discomfort stem from Anu having agency over her own sex life, while Prabha remains celibate, longing for the return of her long-gone husband.

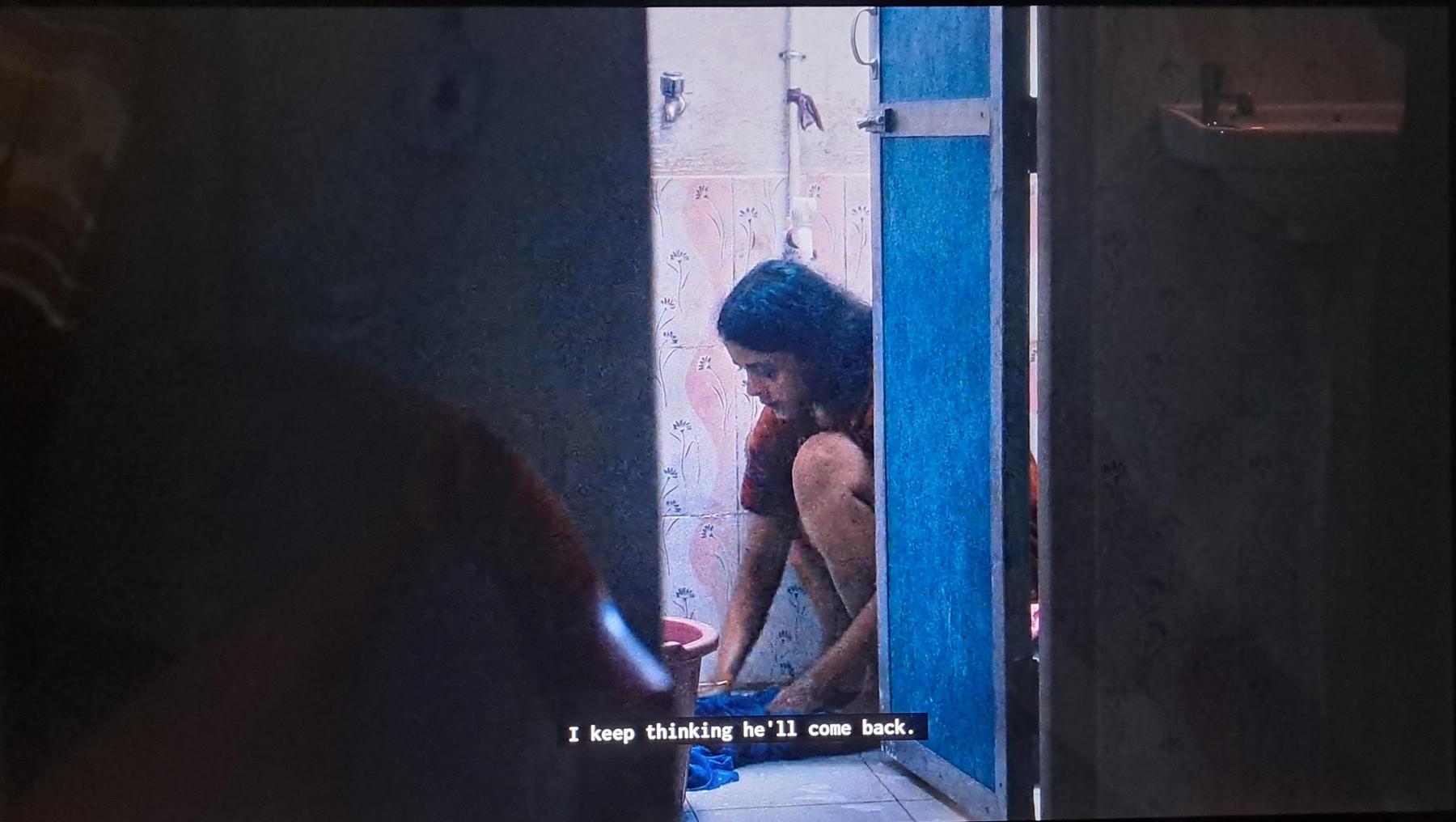

Prabha hoping her husband will come back.

Her sisterhood with the older and the younger woman appears to offer a certain degree of safety and purpose to Prabha that does not create difficulties for her fidelity to caste endogamy until she is confronted by their own aspirations for life—Parvaty wanting to move away from the city and Anu’s relationship with the Muslim man. On the other side of the precipice, the same trio holds the potential of a chosen community created through friendship and solidarity. And maybe it is in the nature of this evolving community to permit intimacies with others, for instance, in the way Prabha eventually asks Anu to “just call him (Shiaz)” to their space.

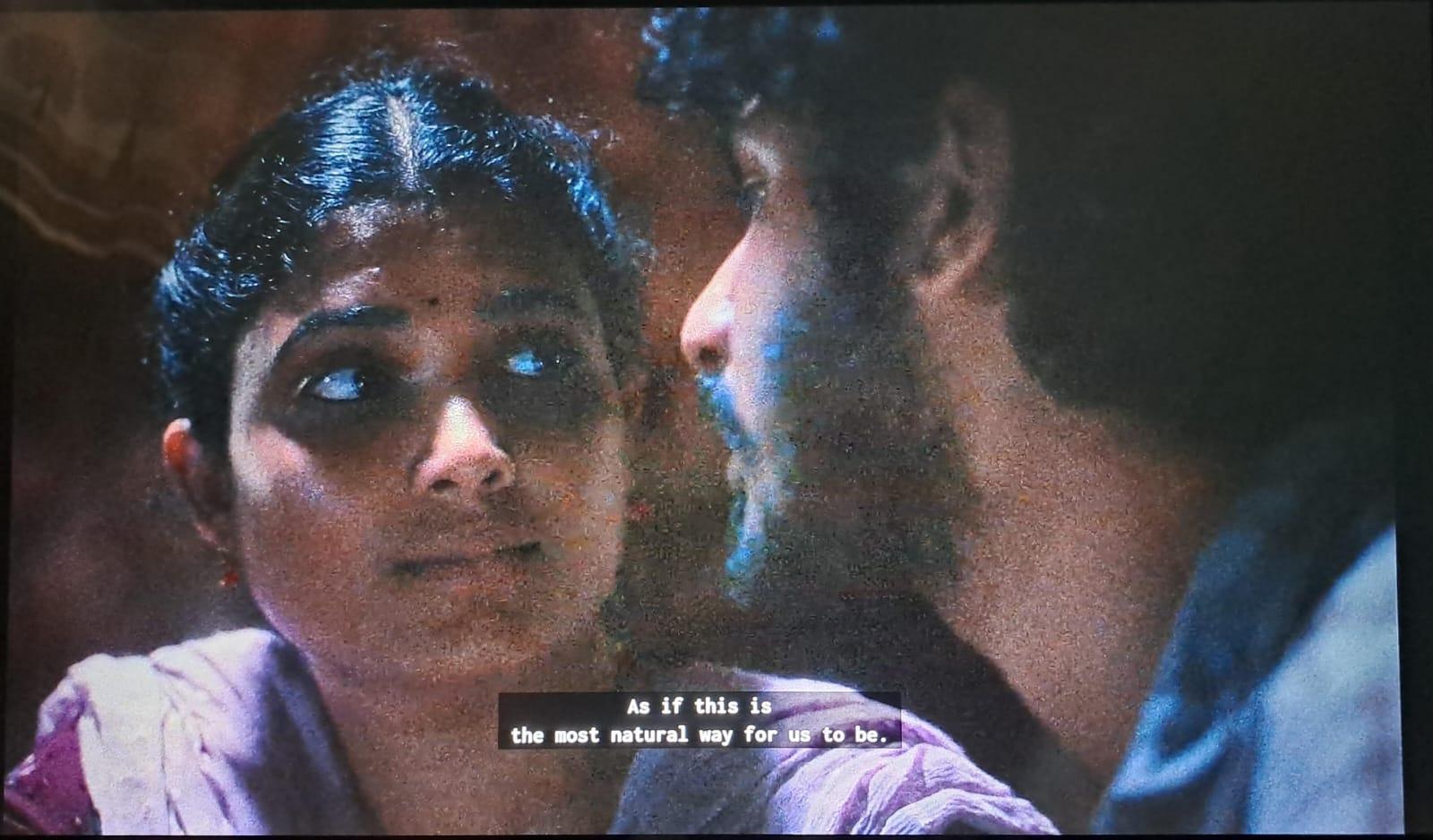

Manoj propositioning a reticent Prabha.

What makes AWIAL political are the ways in which one woman (Anu), while asserting her right to love and over her own body, operates in resistance to the contemporary taboo and violence over interfaith love in India and how the other two women—a reluctant Prabha and a relatively unbothered Parvaty—navigate this resistance. The film holds an important critique of Hindu arranged marriage, which, as Perveez Mody puts it, “...is geared around the assumption that ideally the girl and the boy are strangers to each other and that it is their obligation to their parents that makes them sometimes reluctant, though consenting, parties to the marriage.” This shows up in Prabha’s recounting of her experience of her marriage to a total stranger. She tells Anu: “One day, Father asked me to come back home. When I got there, they’d already fixed my marriage…I tried to meet him (the match)...He had just a few days of leave. When we tried to talk, there were always relatives around.” Here too, the given community forecloses the individual need for knowing a future intimate partner.

The suspicious arrival of the rice cooker.

The cynical nature of such an arrangement is perhaps most evident in the suspicious arrival of the rice cooker from Germany, which is where Prabha’s husband is supposed to live and work. One does not know what to make of it, and yet it is there. Perhaps this gesture from the ambiguous gift giver, presumably her husband, is a meagre price for Prabha’s chastity, a primary condition of the contract of endogamy. In return, Prabha rejects Dr Manoj’s proposition for an affair and keeps the false hope alive that one day her husband will return and want to be with her.

Anu and Shiaz trying to find intimacy outside a football ground in the Mumbai rain.

In a scene that follows Anu and Shiaz passionately making out outside a football ground in the rain, Prabha is seen alone in the bathroom, washing her clothes as she stops to wonder: “I keep thinking he’ll come back. And he’ll say that he wants to live with me and be with me.” Later, in a scene deploying magical realism, Prabha, in an afternoon reverie, dreams of rescuing her husband from the seas that have kept them apart. She has a painful discovery about how unbearable her desired reunion with her husband might be. It might want to take her away from the very potentials for life, love and community of surplus women that she is entangled with in reality.

Anu and Shiaz contemplating about the "impossibility" of their relationship.

Anu and Shiaz’s interfaith love challenges the natural order of things enshrined in religious and caste distinctions and hierarchies. It teases Hindu society’s fantasies about what one might find under the burqa of the Muslim woman: perhaps a Hindu woman about to make love to a Muslim man. The film, therefore, is a subtle and direct critique of Hindu nationalist groups and their conspiracy theories, such as “Love Jihad,” that vilify interfaith love/marriage. Muslim men apparently seduce Hindu girls into a relationship and convert them to Islam through marriage and turn these women into baby-producing machines who will add numbers to the Muslim population and threaten the Hindu majority. In short, interfaith love/marriages are unholy unions that prioritise lust over obedience towards given communities.

A colleague warning Prabha about Anu's relationship with a Muslim man.

Historically, Love Jihad is a repackaged name for the anxieties around interfaith love. This can be traced back to the public outcry against the colonial government’s efforts to legalise interfaith and inter-caste relationships through the Special Marriage Act (1872). Later, this would also be advocated by Dr B.R. Ambedkar and Periyar as a way to disrupt the caste system. Various religious and caste communities petitioned the colonial government that such legal recognition of intermixing would destroy the purity of caste endogamy. These fears and anxieties continue their legacy in the violent acts of policing led by Hindu vigilante groups in collusion with the offended families. A recent video circulated on online media platforms shows Hindu right-wing groups mercilessly assaulting a Muslim man and a Hindu woman inside a Bhopal courtroom at the time of the registration of their marriage. This is yet another example in the long trajectory of reported and unreported cases of violence on inter-caste and interfaith couples.

Anu gossiping about the nurses and patients with Shiaz.

In a way, the film is also a critique of the state that legitimises the Love Jihad conspiracy through anti-conversion acts in various Indian states as well as of Hindu nationalist propaganda films like The Kerala Story (2023), which claims to be inspired by true stories about Muslim men converting Hindu women to Islam and trafficking them to join the Islamic State jihadist group. Unlike the “passive and gullible” Hindu women falling prey to the lustful Muslim men of these discourses, AWIAL’s Anu is shown as having the courage to go to lengths for her sexual freedom and desires. The film effectively decriminalises and desensationalises interfaith love between two Malayalee migrants in Mumbai—Anu and Shiaz—through the lens of everyday and ordinary life.

Anu dressing in a burqa to meet Shiaz.

To learn more about Payal Kapadia’s work, read Najrin Islam’s essays on Kapadia’s oeuvre and A Night of Knowing Nothing (2021) as well as Ankan Kazi’s essay on The Last Mango Before Monsoon (2014). To read more about recent films that comment on the place of women in a patriarchal caste Hindu society, read Akash Sarraf’s essay on Kathal–A Jackfruit Mystery (2023) and Ankan Kazi’s essay on Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh’s Writing with Fire (2021).

All images are stills from All We Imagine as Light (2024) by Payal Kapadia. Images courtesy of the director.