Chambre 666: Is Cinema About to Die, or Is It Already Dead?

Cinema as a medium has constantly been redefining itself, with technological changes shaping and altering how spectators experience it. Cinema, in its inception, became the “seventh art”, which in artistic expression incorporated elements of six other traditional arts: architecture, sculpture, painting, music, dance and literature. In the last decades of the nineteenth century, there was a shift in the reception of cinema from an individual experience to an art mass-produced for public audiences, largely due to the invention of “Cinématographe” by the Lumière brothers, which enabled film projection onto a screen. However, ever since the birth of this seventh art, film theorists, filmmakers and critics alike have announced the “death of cinema”—a proclamation, a statement and an eulogy for the medium. But, the emergence of digital technologies in the 1980s pose existential questions for the ability of cinema to endure as an art form. It is this question that becomes the subject of Wim Wenders’ forty-five-minute-long documentary Chambre 666 (1982).

Title card.

During the 35th Cannes Film Festival (1982), Wenders invited fifteen directors from around the world to Room No. 666 in Hotel Martinez to ponder: “Is cinema a language about to get lost, an art about to die?” The filmmakers were set up alone in a room without any interlocutor, with only the presence of a camera. They had to flick a switch for it to start recording and then speak for a maximum of ten minutes. The documentary begins with a huge and imposing image of a majestic cedar tree from Lebanon, almost powerful in its presence, at the side of a freeway. The image is accompanied by powerful operatic music, resembling silent-era films with a stentorian voiceover of Wenders, who claims the tree to be at least 150 years old. In an optimistic premonition, Wenders says, “The tree has seen the beginnings of photography and cinema’s entire history, which might just as well survive.”

But, similar to “film” (the photochemical process) being seen now as an obsolete technique of recording and reproducing images in the current digital era, the tree has been chopped down and fallen because of natural disease. The Lebanon cedar tree, known for its resilience, strength and endurance, symbolises the “film’s” own endurance in storytelling and its purity of image in the wake of new digital technology within which authenticity becomes dubious. The cedar tree appears thrice in the documentary, once in the beginning, towards the middle, and then in the end, reminiscent of the early traditional storytelling approach with a beginning, middle and end—though Jean-Luc Godard, with his radical approach and subversion of traditional methods of storytelling, once famously said: “A story has a beginning, a middle and an end but not necessarily in that order.” Like the tree, the analogue (film) medium of telling a story is nearly dead too, but the storytelling still survives both in linear and experimental ways.

The Cedar Tree.

Similarly, in his quintessential disposition, Godard reflects upon the question posited by Wenders, deliberating between television aesthetics and cinema aesthetics. He links the question to the advent of television and, soon, advertisements and connects them both to a pivotal point in silent era films with Sergei Eisenstein’s film, Battleship Potemkin. He satirically compares advertisements to Battleship Potemkin and says that the former are only a minute long, while the film is an hour long. Therefore, advertisements operate on a superficial level of information while concealing the hidden truth, whereas a film has powers of revelatory truth because of its long durée medium. Godard implies more films are being made amidst the new technologies.

John Belton, in his essay, “If film is dead, what is cinema?”, points out that VCR and VHS stimulated demand for new films, sending people back into theatres and ultimately becoming its “saviour” by “providing an after-market for consumers.” However, regarding the aesthetic experience of VHS, Godard refutes the claim that people prefer to watch films on tape at home. He calls it a pretext: “a porn movie at home on tape is a pretext to invite a girl, avoiding the minimal work that is talking to her about love.” At one point, after a pause of contemplative reflection, Godard explains what makes cinema different from television; it has the ability to look out for what is invisible, what you cannot see is incredible, and it is the task of cinema to show you that.

(Left) Jean-Luc Godard. (Right) Steven Spielberg.

Filmmakers like Werner Herzog and Michelangelo Antonioni offer an insightful and original take on the subject, a fresh reminder of their invigorating views and idiosyncratic thinking. Herzog compares television to a jukebox and implies that spectators have a mobile position, whereas, in cinema, a viewer is inside a theatre; viewers can switch on and off television as they wish, but they cannot do so with cinema. It brings forth an important discourse around the aesthetic relation between celluloid and reality and the powers of digital technologies to create an illusion of reality. Television and VHS allow viewers to pause, rewind, repeat and skip sequences, thus breaking the temporality of a film. Cinema as a storytelling medium registers both its own story time and the photographic time when the images are actually filmed. The new technological changes disrupt cinema’s illusion of movement and burst through the time of film’s original moment of registration, thus rupturing the artificial narrative structure of cinema.

Antonioni offers an optimistic view, though he believes the existence of cinema is precarious. His views revolve around adapting to changing times and technologies that fit the particular time’s expression. He suggests how different possibilities of video teach us other ways of thinking about ourselves and expressing the same. As with any disaster, calamity, or ecological change, organisms evolve; similarly, filmmakers and our way of expression must.

(Left) Werner Herzog. (Right) Michelangelo Antonini.

Wenders’ choice of a static setting—with closed curtains inside a room and television sets that continually run different programmes, from tennis matches and films to animation—offers a space of contemplation and introspection, reflecting the seriousness of the question it wishes to tackle. The Turkish filmmaker, Yilmaz Güney, who won the Palme d’Or the same year for his film Yol, remained unavailable due to the Turkish government’s demand for his extradition from France and instead shared an audio recording. In his recording, he expresses his views on what he believes to be the two forms of cinema: industry and artistic. The industry cinema for the masses that is advancing cinema has been dominant but is outdated, and the artistic cinema that is blooming is constantly being suppressed, silenced and punished by the state.

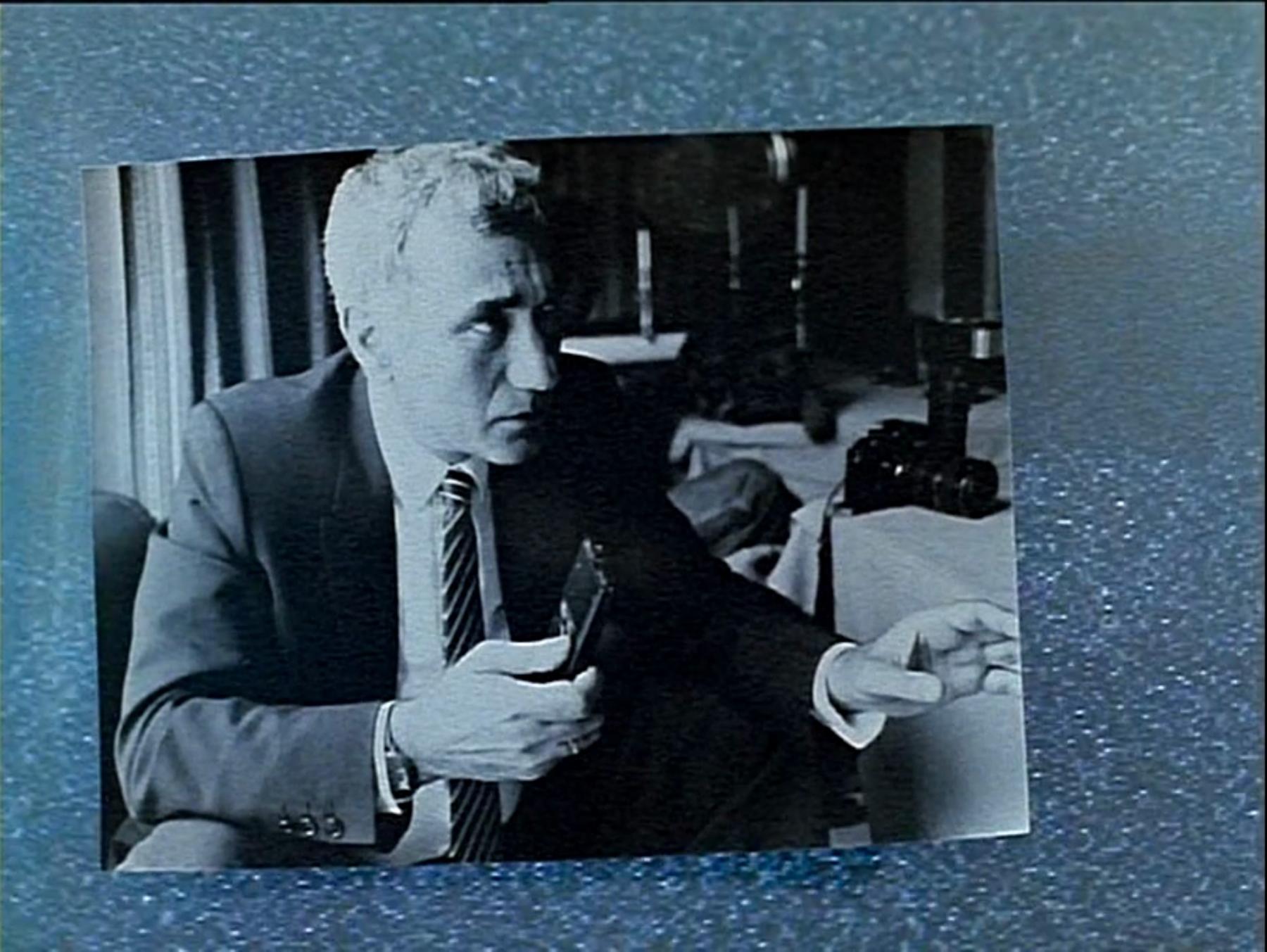

A photograph of Yilmaz Güney pasted on the television set by Wim Wenders.

Therefore, in the twenty-first century, now with apprehensions about AI and its impact on cinema, it can be said that “film,” a photochemical process of making movies, is nearly dead and only kept alive by a few filmmakers and moviegoers, but cinema is still very much alive in the constant flux of technological changes, transforming the form of storytelling and expression and its broader reception in different formats.

To learn more about debates around the arrival of the video moment in India, read Silpa Mukherjee’s essay on piracy in the Bombay film industry and experiments in cinema in the 1980s.

All images are stills from Chambre 666 (1982) by Wim Wenders, courtesy of the director.