Noise, Performance and Protest: On Poulomi Desai's Music Practice

In The Struggle for Black Arts in Britain (1986), Kwesi Owusu rues the Arts Council’s support for the ‘professional’ arts, whereas Black arts suffer due to the lack of structural support. In the first part of this conversation, Poulomi Desai talks about working to build an arts scene for artists of colour, at a tumultuous time in racial and feminist politics in Conservative-led UK in the ‘80s. Growing up, she was surrounded by classical and folk music from India, especially considering the popularity of Ravi Shankar and The Beatles using the sitar in their songs or The Rolling Stones’ track “Paint it Black.” She became involved with post-punk and their political strain with bands like Crass, and then with a Sikh hip-hop group called Hustlers in the 1990s, for whom she designed record covers. Her experiments with the sitar desanctified the instrument, which had become so stereotypically associated with India, and, taking from Luigi Russolo, moved it to the genre of noise music. She said, “I see noise music as protest… In marches and protests, whether it is sirens, trumpets, bands or people banging on pots—I relate more to that. It is the noise of the masses.”

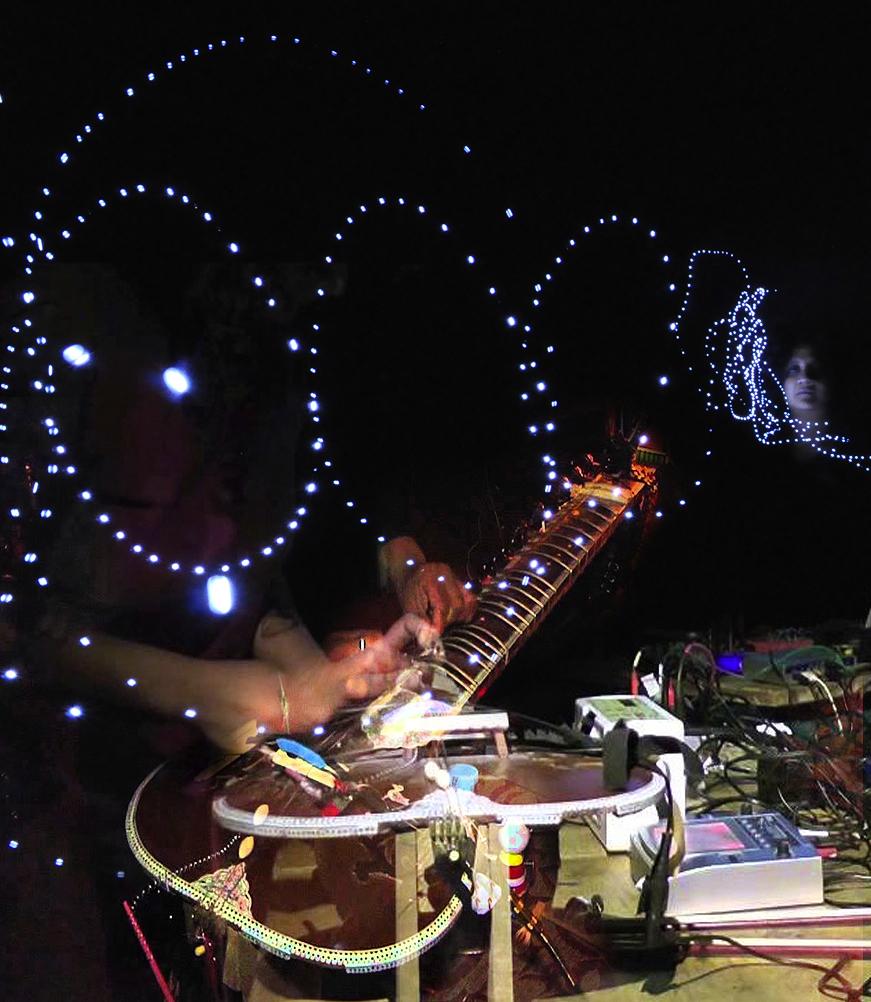

Poulomi Desai performing with her modified sitar.

With the arrival of computers, everyone was deeply concerned with what it means to be human. Desai’s immediate circle—including the likes of Shivananda Khan—were all reading sci-fi. The sitar became a metaphor for the human body and its internal and external noises, referencing the instrument’s origins from a resonant gourd. “These sitars had been donated to me because they were broken,” she said, “Do I mend it? There is a broken body—plus the shapely bum, which made me think of the stereotypes of Black women.” When she was in Delhi, she stepped into Rikhi Ram—whose owner is said to have introduced the sitar to The Beatles—and discovered a whole new realm of Indian experimentation with instrument-making.

Poulomi Desai performing at Cafe Oto in London in 2014.

In a performance at Café Oto, the modified sitar sits on the table, surrounded by distortion pedals and circuit bent toys, which transform the usual sound of the sitar. Desai plays on it using everything but her fingers—a fiddlestick, kitchen knives and a vibrator. To remove the tactile body, which becomes so significant in classical performance, she created a metal hand for a self-modulating version. “Would it just run until you switched it off?” she said, “How could you interfere with it? You could put your hand on the top and it would change—like a Theremin.” Often playing with Simon Underwood of The Pop Group, as part of the improvisatory duo (sometimes trio) Conspirators of Pleasure, they would let the sound machines run after a point, depending on chance—including the possibility of it breaking, once again.

Poulomi Desai and Simon Underwood (founder of punk band The Pop Group) performing as part of their band, The Conspirators of Pleasure, where they create performances using self-regulating sonic systems using modified and prepared instruments.

Desai worked with spatiality from a political lens. In the video work Over the Horizon (2004), the silence of the lack of human sound is overpowered by eerie recorded noise. It overwhelms her photomontages of the uninhabited Orford Ness—an island which became a test space for research during the Cold War and was used to test Britain’s first atom bomb. In 1997, Talvin Singh had released the compilation album Anokha–Soundz of The Asian Underground, and the idea of sound from the margins fascinated Desai. In a Conspirators of Pleasure performance at Khoj in 2013, they projected colours that would change in synch with the sound frequencies onto a half-developed building in Khirkee Extension, an area where many migrant workers live in Delhi. She interprets spaces sonically through Very Low Frequency (VLF) electromagnetic recordings, which are often used by the military for secure communication. Taking from the audio piece “Étude aux Chemins De Fer [Railway Study]” by Pierre Schaeffer in 1948, in collaboration with Joe Banks of Disinformation, for a project with INIVA, London, they recorded VLF and visuals of landscapes from the Underground as it moved from the suburbs to the centre. The political nature of Indian railways—through colonialism and, then, through development initiatives like the metro—has been captured through a VLF recording of the metro amidst the rush of people, with visuals of various locations in Delhi, from malls to upcoming construction projects.

London Underground VLF' by Poulomi Desai and Disinformation.

Radios have been integral during wars in the twentieth century. In Raga Radiophonic, Desai and Banks made radio recordings created by electronic changes in light patterns to generate something akin to acid house, with flashing LED light videos. The hypnotising potential of light and sound was taken further in her Dreamachine series from 2012. Inspired by Gysin’s Dreamachine (1961), Desai induces noise music that takes from beatboxing and upbeat club tracks, with flashing colours on video, with silences when black flashes up. “The sound waves that make up pink noise have the same frequency as light waves that create the colour pink, though the hue varies,” she had observed then. After a series of murders in Myatts Fields, a park in South London, in 2006, Motiroti commissioned her to respond through her art. She created a sonic installation from her field recordings, capturing sounds of wildlife, mingled with the sound of police sirens. “Some guys there were trying to be macho—they had huge, aggressive dogs,” she recalled, “I was live mixing as well. When the dogs went by, I would push up the sound of wailing wolves and the dogs would whimper and cower away—in a way they became performers.”

Raga Radiophonic—Part I' by Poulomi Desai, which are a series of live, kinetic, electrical, radio recordings and electronic Rangoli lightbox installations—an acid house, noise influenced, hypnogogic meditation on Kali Yuga.

In 2003, she formed Usurp Art mostly with people she knew, but also through callouts through community groups and online. Alongside workshops, they exhibited artists like Mona Hatoum, Max Eastley and Steve Beresford. In 2010, with a new studio at Harrow, after Chila Burman was rejected for the summer exhibition at the Royal Academy, they programmed a solo exhibition for her, calling it Chila Burman’s Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. Here, Burman used her “‘worthless’ materials, the pretty ‘girly’ detritus that many would consider cheap kitsch.” Desai recalls, “She did massive collage murals with local communities and young people… So there was dialogue between very different people around Chila’s work. I had secretly hired an ice cream van run by this white guy who collected postcards of her work.”

Poulomi Desai at the opening of Chila Burman's Royal Academy Summer Exhibition at the Usurp Art Gallery in 2010.

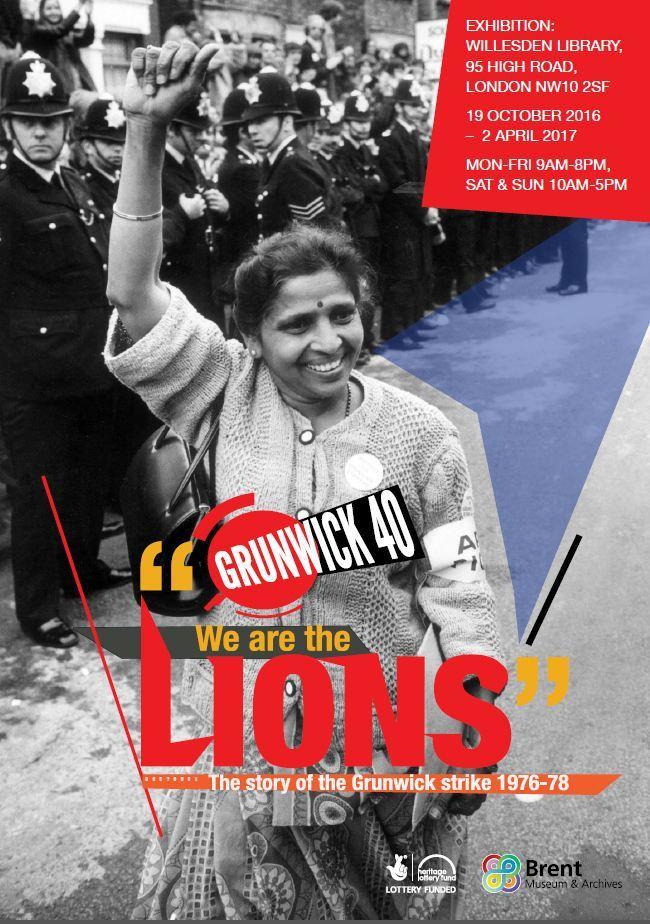

Upon forty years of the Grunwick Strike, trade unions and local activists got together, and she became the curator of the exhibition We are the Lions–The Story of the Grunwick Strike 1976-1978 where massive murals and banners marked the gallery, which moved beyond the walls into community spaces through workshops and conversations with the protestors. In 2006, Desai worked with Motiroti on Priceless, commissioned by The Serpentine, where they mapped the community of traders, museum workers and licensed buskers who would frequent South Kensington station—working with London Underground staff which culminated in a map throughout the tunnel. “The project was almost like a tester for it to get people on the streets and see how traffic would behave,” she said, “They wanted to pedestrianise the street where all the museums are. We had mobile units that looked like tiki bars. Installations, projections and dancers—all sorts of stuff going on.”

Poster for We Are the Lions—The Story of the Grunwick Strike 1976-1978.

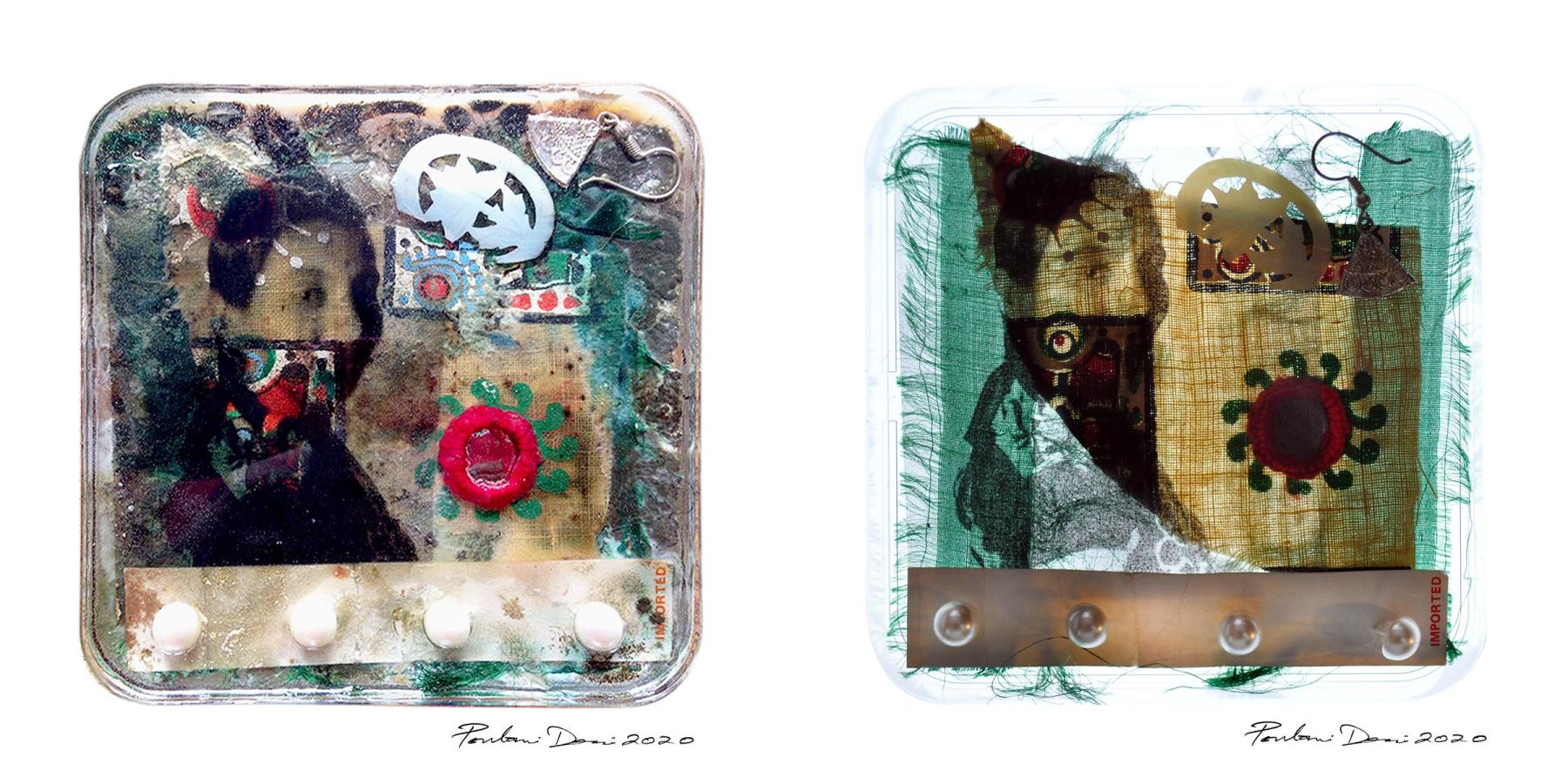

When Misery, a mental health collective with sober club nights for queer people of colour opened, Desai installed projections of photographs from her past work of South Asian queer people. These were reflected on their bodies, such that they could respond by generating a set of layered images. Some of them were even images of bacterial slides, which Desai had grown in the ’80s, taking on the character of an Edwardian researcher. She restarted the project in COVID, gathering bacteria from her mother’s mouth or face and creating plates for them to grow, adding old photographs, religious texts and textile pieces. “What would they cover and what would they destroy,” she had wondered, once again working with probability and chance.

Our cultures are the portals—the gateways between one world and the next (2020) commissioned by Autograph ABP.

In case you missed the first part of the piece in which Desai discusses race and queer politics in Britain, read it here.

To learn more about music as protest, read Natasha Gasparian’s essay on the role of jazz in Johan Grimonprez’s Soundtrack to a Coup d’État (2024) and Upasana Das’ two-part conversation with Shahbano Farid on Karachi’s underground music subculture.

All works by Poulomi Desai. Images courtesy of the artist.