Cycles of Enclosure: Caste, Class and the Unequal Marriage “Market” in Jayant Somalkar’s Sthal

Premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2023, where it won the NETPAC award for best film from the Asia-Pacific region, Jayant Somalkar’s Marathi film Sthal (A Match) develops in between iterations of the ‘kanda-poha’ programme—formal meetings for bride selection that take their name from the popular Maharashtrian snack that is typically served in such situations. It is as if the spaces in between these meetings take on the task of filling out the blanks left by the meetings themselves; blanks about Savita’s (Nandini Chikte) individuality, her life, thoughts, dreams and ambitions—all things she is stripped of through the repetitive and reductive questions posed in these gatherings.

The meetings reduce Savita, an ambitious BA final-year student, to her physical attributes such as her height and the colour of her skin, all the while laying bare blatant social hypocrisies. Early on in the film, a diminutive boy, part of one of the visiting parties, points out self-importantly that Savita would be inappropriately matched with their tall groom. Again, when her lighter-skinned friend and college mate finds a match, the news is juxtaposed with one of Savita’s own snubs, its reason implicitly stated. At the same time, Savita is bound in an identity imposed by the economic and occupational disparities between her family and those of the suitors who come to ‘see’ her. The superiority assumed by the relatives of potential grooms, almost customary in patriarchal setups, is infused with class and caste prejudices based on vocation. Savita’s family belongs to the Kunbi farming caste—although they own their own land, they appear to be small landowners; unable to afford farmhands, they cultivate their own fields. Several scenes show the family labouring on their land, picking cotton, storing and weighing bales at home and carrying them in carts to nearby towns to sell.

The film sharply reflects the prejudice against agricultural caste communities, amplified in the context of the “marriage market”: boys with government jobs—factory supervisors and college professors—are valued higher. They are capable of demanding a significant dowry and are bestowed with more choices when compared to potential grooms and brides from farming households. Not only does Savita, the daughter of a poor cotton farmer, suffer as a result, but so does her brother Mangya, who loses his girlfriend to a suitor with a job. Endogamous traditions, as Dr BR Ambedkar has argued, are the genesis of caste and the basis on which caste hierarchies are maintained and propagated. The Kunbi swayamvara (ceremony to select a husband) that Savita is forced to attend is representative of this nexus between class and caste and their cycle of enclosure and immobility. In an extended sequence in the film, hierarchical inequities between the potential bride and groom’s sides become apparent. The boy’s side goes bride shopping, literalised in a scene where the father of Khapne—Savita’s sociology teacher who claims to want to marry her—takes his pick at a vegetable market and bargains for a higher dowry price for his son on the phone, all the while moving from one vendor to another in search of a lower price to purchase his daily stock. In stark contrast, Savita’s father Daulatrao desperately tries to take a loan and puts his land—the family’s sole source of livelihood—up for sale, all in the hopes of getting his daughter married.

Moreover, Somalkar reflects the unmistakable anxiety around women’s education; even as little school-going girls celebrate the example set by feminist icon, teacher and social reformer Savitribai Phule, it is a meeting with a potential suitor that costs Savita a hard-earned opportunity to appear for the state civil services exam. Savita’s mother Lilabai wonders about the implications and potential imbalances caused inadvertently in society by educated women as boys like her own son remain unemployed. Hence, when the family is presented with the choice between meeting a suitor and Savita’s MPSC exam—a situation they find themselves in because the suitor’s dates are inflexible—they struggle with the decision. But in the end, it is her dream of a career that is forfeited, laying bare the contradictions between the promise of education and possible futures for young women.

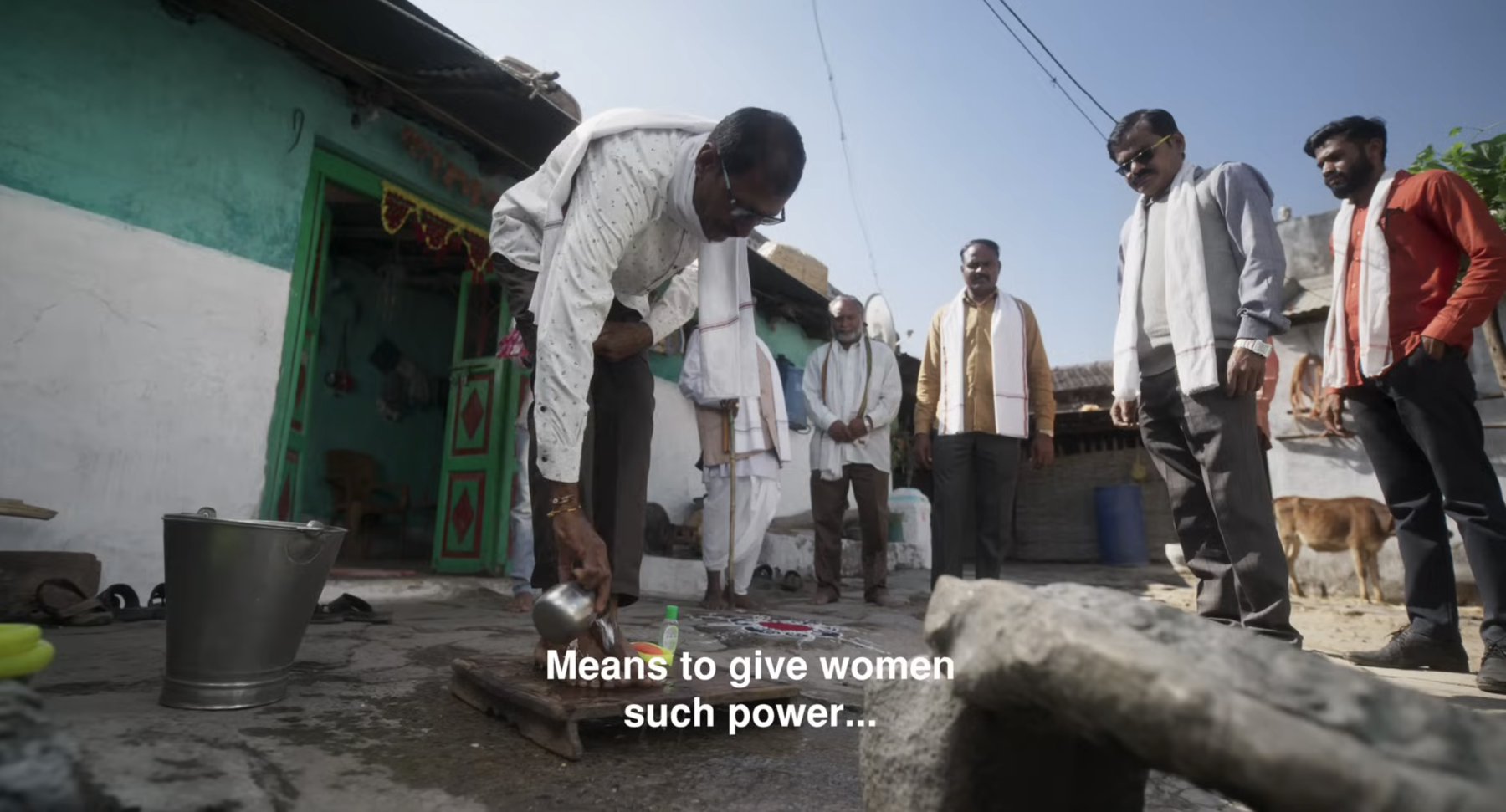

Somalkar, who shot the film in his native Dongargaon in Maharashtra, has spoken of having witnessed several such match-making meetings growing up, which explains his meticulous depiction of their ritualistic nature. The assumed formality and seriousness apparent in the step-by-step progression of these gatherings—from the hosts patiently waiting on the guests as they wash their feet and rinse their mouths to the passing around of a betel nut box and a post-interview huddle in the courtyard—give them the quality of a dark comedy. At the same time, they reinforce the inflexibility of the convention. In fact, so formulaic and rehearsed is the make-up of these arranged meetings that Somalkar distils them into a series of effectual images: a soap and a jug of water left outside for the guests to wash their hands and feet with, a cluster of sandals that they have removed before entering the house, a hurriedly drawn rangoli (decorative design traditionally made on floor outside homes), a towel hung on a clothesline to dry, which is ironically inscribed with the word “qurbani” (sacrifice)—innocuous signs of the proceedings indoors and objects that through repetitive use become symbols of Savita’s oppression.

We see this ritual play out four times over the course of the film. The first is a dream sequence where its gender dynamics are reversed. And then three more times, each shorter than the previous one, to mark the viewers’ familiarity with the process, rendering it more dehumanising as a result. In the final sequence, Savita sits expectedly in the centre, small and subdued, surrounded by a group of men and subjected to the same series of stultifying questions we have seen her fielding throughout the film. But there is one striking difference: instead of sheepishly disappearing behind a curtain as she has done many times before, she looks directly at her questioner, storms towards him and administers a slap.

Does Savita, betrayed and at her wits’ end by this point, really strike a prospective ‘candidate’? Or is it merely a moment she imagines—the way she had once envisioned marrying her college professor, believing him to be as dreamy and progressive as his lectures on women empowerment and equality? The slap, whether it takes place or not, holds the power to break patterns at both literal and metaphorical levels. Visually, each of these meetings has a circular layout with a group of men seated encircling the girl on whom all eyes are trained. Meanwhile, the rest of the womenfolk toil away unseen, hidden behind a curtain. A girl being evaluated for a match cannot be a part of this select male circle, only its focus. By choosing to leave her assigned exhibitory position and instead walk up and confront her questioner, Savita disrupts this circle’s geometric sanctity, just as her act, one hopes, will potentially interrupt this recurring cycle of devaluation. Moreover, since the scene appears soon after one set in the reading room of Savita’s university, where we are briefly given a glimpse of an Ambedkarite poster with the slogan “Educate, Agitate, Organise,” Savita’s act must be seen as a stirring to this clarion call. Given that the family are Kunbis who labour on the land, it also acts in alignment with Jotiba Phule’s call for a ‘Stri-Shudra-Atishudra’ alliance, unifying all sections exploited by the brahmanical, patriarchal order.

And what of the imagined recipient of the slap? Is it only the suitor—one whom we do not even get to see? And is the reason we do not get to see him that we, in fact, are him? Sthal’s unexpected final shot is reminiscent of another jolting closing image—the fourth-wall breaking stone throw at the camera in Fandry, Nagraj Manjule’s searing debut about caste discrimination set in rural Maharashtra. In this sequence, Somalkar’s camera, like Manjule’s, is positioned not as a witness to the scene but as an active participant, merging with the point of view of the oppressor so that when the oppressed finally revolts, the instrument of their fury—the slap, the stone—is directed squarely at us, the viewers. Whether or not the ‘candidate’ of this particular ‘kanda-poha’ episode gets smacked in the face in the film, the slap that Savita envisions as an indictment of the society that has enabled this ritualised humiliation hits palpably hard.

To learn more about recent films commenting on the place of women in a patriarchal caste Hindu society, read Ria De and Koonal Duggal’s essay on the possibilities of love within caste hindu endogamy in Payal Kapadia’s All We Image As Light (2024), Akash Sarraf’s essay on Kathal–A Jackfruit Mystery (2023) and Ankan Kazi’s essay on Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh’s Writing with Fire (2021).

All images are stills from Sthal (2023) by Jayant Somalkar. Images courtesy of the director.