It Takes a Funeral to Celebrate: On Dalit Subbaiah

Film poster for the documentary Dalit Subbaiah: Voice of the Rebels (2025).

In celebration of Dalit History Month, MKP Gridaran’s Dalit Subbaiah: Voice of the Rebels (2025) was screened at the PK Rosy Documentary and Short Film Festival as part of the fifth edition of Vaanam Art Festival, organised by filmmaker Pa. Ranjith’s Neelam Cultural Centre in Chennai. The film is a musical documentary stitched together by the slogans raised at a funeral procession for the revolutionary singer Subbaiah.

A gentle, unassuming revolutionary gets ready for his performance at Margazhiyil Makkalisai 2020.

With a triumphant Red salute, the film starts off with visuals of Periyar and Ambedkar and then establishes Subbaiah. Slowly, in black and white, a gentle, unassuming revolutionary gets ready for his performance at Margazhiyil Makkalisai 2020. Margazhiyil Makkalisai is a radical music festival that emerged as a response to the Brahmanical dominance of Carnatic music, reclaiming Margazhi for the voices and rhythms of Tamil working-class and Dalit communities. The film then cuts to Subbaiah’s funeral, his body surrounded by comrades proclaiming, “Veeravanakkam! Veeravanakkam!! (Valiant Salute!) For our comrade who flayed Brahminical fascism with his independent music.” In the next scene, Subbaiah calmly gets ready and steps out to sing on one of the biggest stages he has ever performed at.

Rapper Arivu at Subbaiah's funeral. Arivu performed Subbaiah's songs for his auditions for the Casteless Collective. Such was the impact of Subbaiah across generations.

Margazhiyil Makkalisai, the brainchild of rapper, singer and songwriter Arivu and director Pa. Ranjith, began as a response to Carnatic music being projected as the musical identity of Tamil people. Organised during the Tamil month of Margazhi (17 December–14 January)—which till then was exclusively considered and celebrated as the month of Carnatic music performances—Makkalisai showcased alternate, more popular forms of music that have existed simultaneously alongside the hegemonic Carnatic music of the Sabha (institutional gathering). Sabhas, historically dominated by upper-caste patronage, institutionalised Carnatic music as the cultural mainstream, sidelining the rich diversity of Tamil music traditions practiced by marginalised communities. While many Sabhas refused to host Makkalisai, a few agreed, mainly to fill in the dates which were not already occupied by conventional Carnatic performances. The last day of the festival was held at the Music Academy, arguably the most important Carnatic music institution in Chennai. While the fact that it took Subbaiah thirty years to reach a stage of this size is a great irony, it is also a giant leap in the domain of Tamil music, where Carnatic has been the mainstay for centuries—largely due to the enduring stronghold of Brahminical power over the music industry and its institutions.

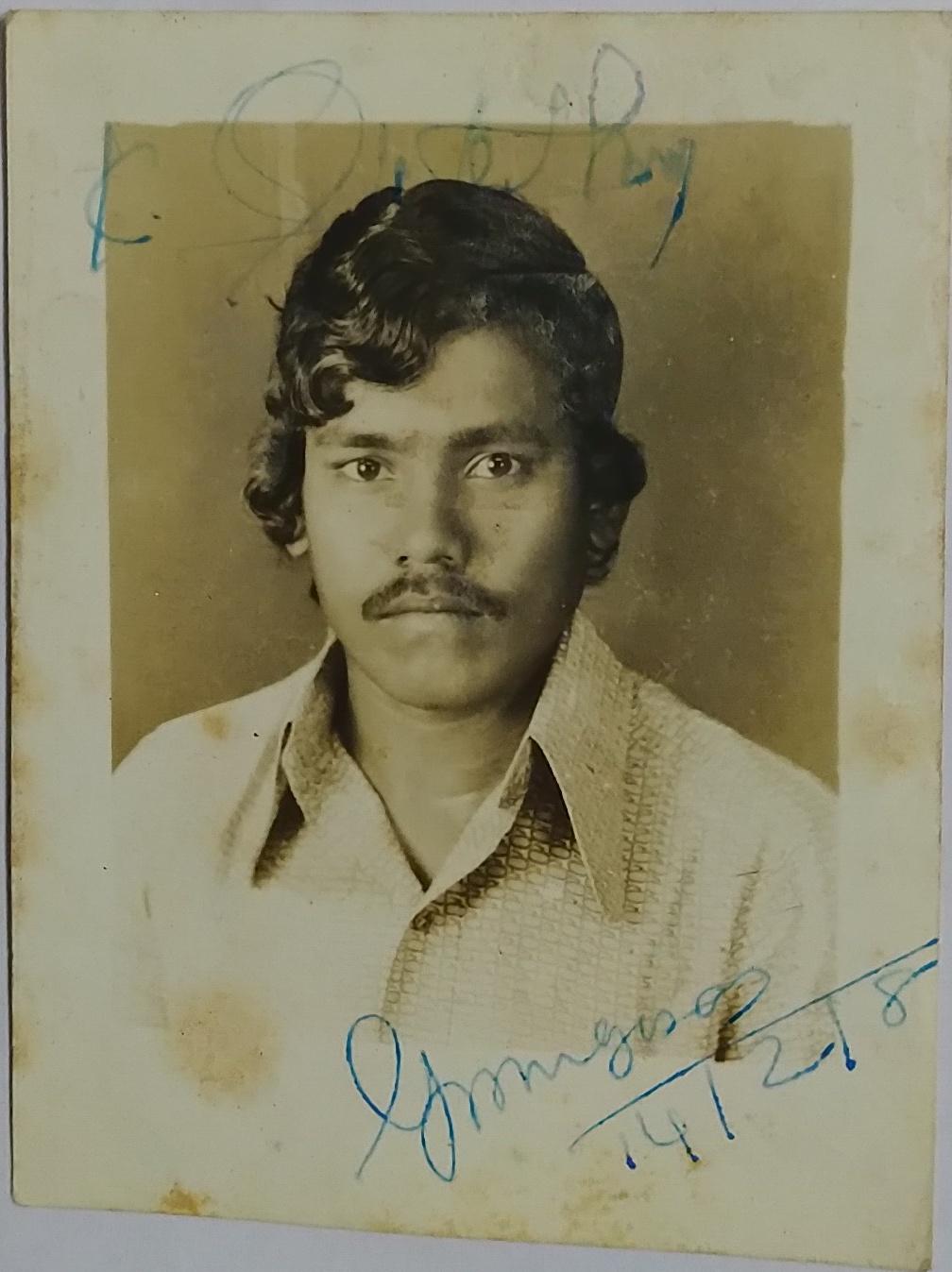

Archival image of young Subbaiah. (Image courtesy of the Subbaiah family.)

The film moves on to narrate Subbaiah’s childhood. It references the Muthukulathur anti-Dalit incident of 1957, during which Dalit housing was burnt down and his parents were forced to move. They later settled down near Madurai, where he was born. Even though it took him years to fully grasp the caste politics that shaped his oppression, Subbaiah’s early political awakening came through the influence of Communist comrades who were deeply embedded in Tamil Nadu’s grassroots movements. Subbaiah named his children Spartacus and Gorky. When Gorky was bullied at school for his name, Subbaiah accompanied his child the following day to explain the person behind the name and his importance, a reflection of his focus on education and direct conversation with the people.

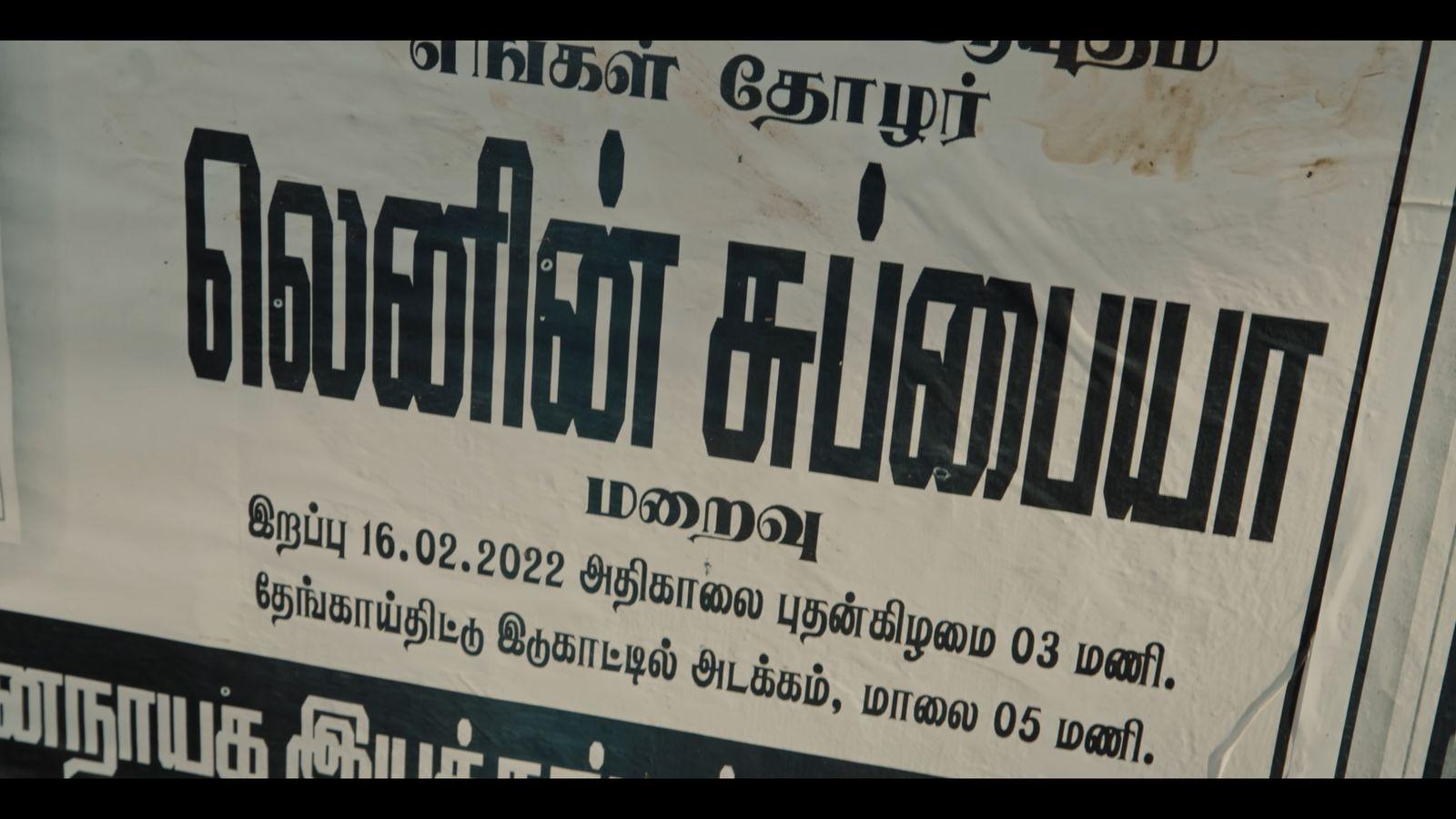

Obituary poster of “Lenin” Subbaiah around Pondicherry.

During his later years, preferring to call himself Lenin Subbaiah, he went on to name children in his town with names such as Stalin, Bhagat Singh, Jenny, etc., with the hope that these names would keep alive the ideas they once propagated. In the documentary, Aranga Gunasekaran, State President of the Tamilaga Makkal Puratchi Kazhagam, recounts the incident of Dalit Subbaiah becoming Lenin Subbaiah. Subbaiah did not adhere to the idea of identity restricting or restraining oneself or their creation. He wanted to address the notion of oppression.

Viduthalai Kalai Kuzhu performing after the demise of Subbaiah.

During his early years, he worked with the NGO Samathuva Samudhaya Iyakkam (SSI). Then, to streamline his activities, he formed a music troupe called “Viduthalai Kalai Kuzhu” (Voice of Liberation-A cultural troupe) and began functioning independently. The group evolved to being the cornerstone that took Ambedkar’s ideology and addressed various forms of oppression faced by the people through music. The film builds on this narrative with interviews from the members of Kuzhu, many of whom had worked alongside Subbaiah from the very beginning. The documentary also follows his music collections, which were released as compact discs through collaborations with various organisations.

In one CD named Dalit Yugam, he criticises existing caste-based atrocities within Christian communities, which were undocumented till then. While many who converted did so in order to escape the clamps of caste within which they were bound, they continued to practice caste and its hierarchies, a reality that one of the first female Dalit voices in Tamil literature, Bama, has recorded in great detail in her first novel Karukku.

The film matches Subbaiah’s honest ferocity; which was a defining feature of his work.

“பணிந்து போகமாட்டோம் - எவனுக்கும்

“பயந்து வாழ மாட்டோம்

“தலித்து என்று சொல்வோம் - எவனுக்கும்

“தலை வணங்க மாட்டோம்

“அடங்கி வாழ்வது அடிமைத்தனம்

“அடித்து நொறுக்குவது தலித்துக் குணம்

“We will not bow, and

“We will not live in fear anymore

“We are Dalits, and

“We will not bow down to anyone

“Living in chains is slavery

“And breaking through them

“Is the nature of Dalit bravery!

“தொட்டாலே தீட்டு படுமா(ம்)! - நாங்க

“தொடாத பொருள் எதுவா(ம்)

“இந்த கொடுமையை செஞ்சது இந்து மதம்!

“அதை குழிதோண்டிப் புதைக்கணும் அவசியம் அவசியம்!

“They say touch is enough to pollute;

“Tell us, is there anything

“That hasn’t been touched by us?

“Hinduism caused this cruelty

“We must dig its grave immediately!

Subbaiah’s songs stand as symbols of strength amongst those working on the ground to remedy social evils and offer slogans and campaigns that drive strong social messages. In the film, his son Spartacus explains that the main aims of Subbaiah’s music-making process were that “everyone should get it, it should pass the message effectively, and the words should flow according to the rhythm.” He strove to create songs that would make people see the chains that they were bound by.

Manimegalai and Karthi at home.

In archival footage, he remarks on the governing structure of independent India: “The government has no solid plans to eradicate the caste system but rather has in many ways safeguarded the stratification in this caste-ridden Indian society.” In their interview, Manimegalai and Karthi, long-time members of Viduthalai Kalai Kuzhu, express their anxiety on stage when Subbaiah openly critiqued J. Jayalalithaa, then leader of the ruling party, AIADMK. Kuzhu had many confidants over long period of time, like singer Nayagan who then reminds the viewers of what Dalit Subbaiah had told him: “Nayagan, my voice is not that of an individual, but a voice that has risen out of the collective consciousness of countless Dalits.” Subbaiah would go on to remind Jayalalithaa by saying “Do you remember what happened to Hitler in his last days, madam?”

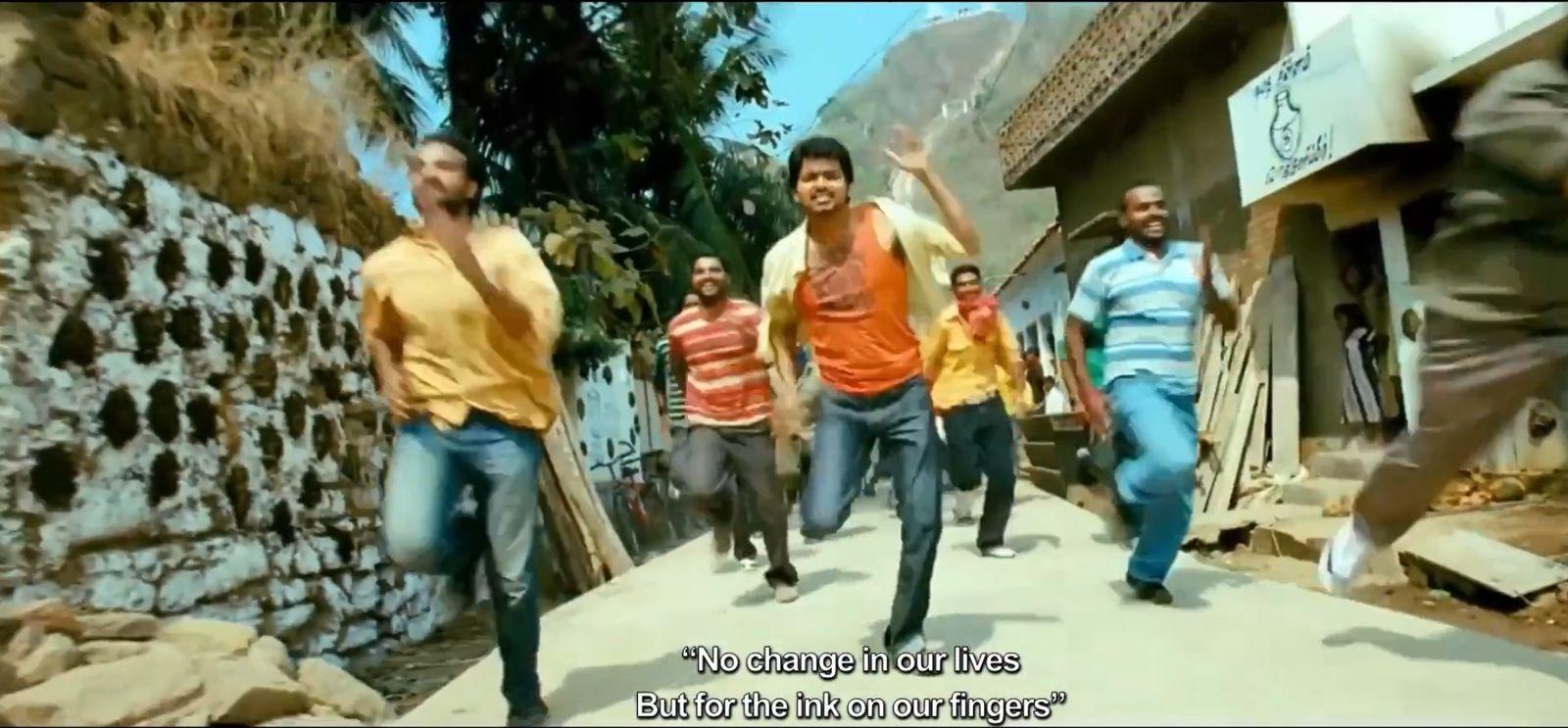

Still from the movie Vettaikaran (2009), which uses Dalit Subbaiah’s lyrics in the opening mass hero song.

Dalit Subbaiah has banked heavily on the collective ownership and preservation of oral traditions and folk songs for his tunes. He added more to the body of work with his every creation, never exploiting it. The movie documents how his powerful political lyrics even found their way into a mass commercial film starring Vijay (who recently inaugurated a new political party).

Subbaiah proclaims on stage in the film, “We sing about Periyar, never about Pillaiyar; we sing about Ambedkar, never about Ayyappan” By choosing such polarising images (radicals like Ambedkar and Periyar to vernacular idols like Pillaiyar and Ayyappan), he substantiates his stand as deeply ideological and rational. One of the two living beings he had sung about was Maestro Ilaiyaraja, the other being Thirumavalavan. Subbaiah addresses the fact that Tamil cinema, until the advent of Ilaiyaraja, was controlled by the tambhura and mridangam of Carnatic descent. Ilaiyaraja helped create a shift towards a more lively and rooted music, which made music accessible and reinforced the idea that music was for everyone.

The funeral it took. Dalit Subbaiah's funeral procession at Pondicherry.

The film documents different factions using either “Lenin” or “Dalit” during his funeral according to the ideologies they subscribed to. Ultimately, the film makes it clear that regardless of what one might call him, Subbaiah and his work transcend such identifiers. Thus, through the film, Subbaiah reminds the viewer that revolutionary songs die when the issue being addressed dies, not in the absence of the musician.

Engaging with the locality in which the funeral procession took place, the film shows a shopkeeper on a street corner saying, “He used to come around quite often but never did I know the impact he has had on others in his lifetime. Now looking at all the people gathered here, he should have been quite something!”

An audio recording of a conversation between Subbaiah and Settu (long time confidante and member of Viduthalai Kalai Kuzhu) plays at the end of the film. “Settu, don’t you think people swarm around you when you die out of the guilt of doing nothing when the person was alive?” says Subbaiah, succinctly capturing the essence of the documentary as well as the trajectory of his life at large.

Lenin Subbaiah's rememberance gathering at Pondicherry.

To learn more about forms of cultural resistance against caste, read K. Sajaya’s tribute to GN Saibaba, Sukanya Deb’s interview with Vishal Kumaraswamy’s work ಮರಣMarana [Demise], Ankan Kazi’s review of Writing with Fire (2021), Prabhakar Duwarah’s conversation with Supriya Dongre about examining the oppressive nature of language through her practice.

All images are stills from Dalit Subbaiah (2025) by MKP Gridaran. Images courtesy of Neelam Productions, Yaazhi Films unless otherwise mentioned.