Marathi Cinema: Cultural Memory and Hegemonic Nationalism

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a pronounced assertion of Marathi regional identity began to take shape, laying the foundation for linguistic politics and regional consciousness. While the state of Maharashtra was formally established on linguistic grounds in 1960, the invocation of the Maratha historical past as a marker of regional identity had been prevalent since the late colonial era. At the same time, “Maratha” as a caste identity was itself being consolidated and reinforced during this period. Historically fluid and not confined to rigid caste boundaries, the Maratha category was increasingly associated with Kshatriya status under colonial influence, elevating its social standing. From the 1940s onwards, the rise of Marathi cinema played a pivotal role in popularising both this Kshatriya-Maratha narrative and a broader Marathi linguistic identity, using vivid visuals to narrate tales of regional pride, valour and historical continuity centred on the Maratha Empire and its prominent figures. While celebrated for its artistic and emotional impact, Marathi cinema also served as a vehicle for ideological messaging, shaping popular perceptions of Maharashtra’s history and cultural identity. It was primarily done by emphasising certain narratives while marginalising or distorting others, thus fostering a distinct social and political identity that resonated widely across the region.

The origins of Marathi cinema are deeply intertwined with the early history of Indian cinema itself. The first full-length Indian feature film, Raja Harishchandra (1913), was directed and produced by Dadasaheb Phalke, a pioneering figure from Maharashtra often hailed as the "Father of Indian Cinema." During this formative period, Marathi cinema was primarily dominated by silent films, with mythological and devotional themes drawing from epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata. These films often promoted moral and cultural values rooted in social conservatism and a subtle anti-Muslim political consciousness. The studio system in India began to take shape with companies like Maharashtra Film Company (founded by Baburao Painter in 1918 through the patronage of Chattrapati Shahu, the erstwhile ruler of the princely state of Kolhapur and one of the foremost non-Brahmin voices of western India), which played a crucial role in institutionalising film production in the region. During the 1920s, films such as Savkari Pash (1925) addressed themes of social oppression, reflecting Marathi cinema’s initial interest in issues of social reform and critical commentary—concerns that were first brought into the public sphere by the Satyashodhak Samaj, founded by Jotiba Phule in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

This still from the 1952 Marathi film Chhatrapati Shivaji captures a decisive moment of emotional intensity, where Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj appears visibly distressed and enraged upon hearing about the harassment and trafficking of Hindu women by invading Muslim rulers, often referred to in the film as parkiya (outsiders). (Source: YouTube.)

However, the historical genre came to dominate Marathi cinema as it proved highly effective in capturing the interest and imagination of the wider audience. Early films such as Baburao Painter’s Sinhagad (1933) and V. Shantaram’s Netaji Palkar (1927) dramatised the various episodes of Maratha history with patriotic fervour, reflecting the tendency of the non-Brahmin movement to valourise the category of Maratha as warrior and towards claims of Kshatriya status, particularly following the death of Phule who had instead advocated for a Shudra-Ati-shudra combine toward a Bahujan society. Thus, Sinhagad, based on the popular novel Gad Ala Pan Simha Gela, heroically depicts Tanaji Malusare’s sacrifice during the Battle of Kondhana, establishing a cinematic vocabulary of Maratha valour. Netaji Palkar similarly portrayed a Maratha general’s return to his Hindu faith after a supposedly forced conversion by the Mughals. While these early films on historical content carried subtle but problematic undertones, overtly prejudicial and binary narratives casting Muslim rulers as tyrannical and culturally alien became more systematic in historical cinema in the next phase, which began in the 1940s.

From the 1940s onwards, Marathi historical cinema developed a distinctive framework rooted in socially conservative, Brahmin-centric narratives. This cinematic turn gained prominence in the context of shifting political dynamics after the 1930s. Following the death of Bal Gangadhar Tilak in 1920, the Maratha caste emerged as a dominant yet complex force in the region, exerting significant influence in rural society and post-independence politics. However, despite their political prominence, Maratha cultural representation in cinema remained largely shaped by Brahminical narratives that foregrounded Brahmin characters and ideals. This portrayal celebrated Maratha valour and Kshatriya identity but often subordinated their agency to Brahmin intellectual and moral authority, reflecting broader caste hierarchies. The Brahmin-centric focus in cinema, influenced by colonial historiographies and nationalist agendas, marginalised the Maratha caste’s full historical complexity, contributing to cultural tensions that would later surface in Maharashtra’s social and political landscape. The ascendance of this narrative became conspicuously prominent in the late 1940s.

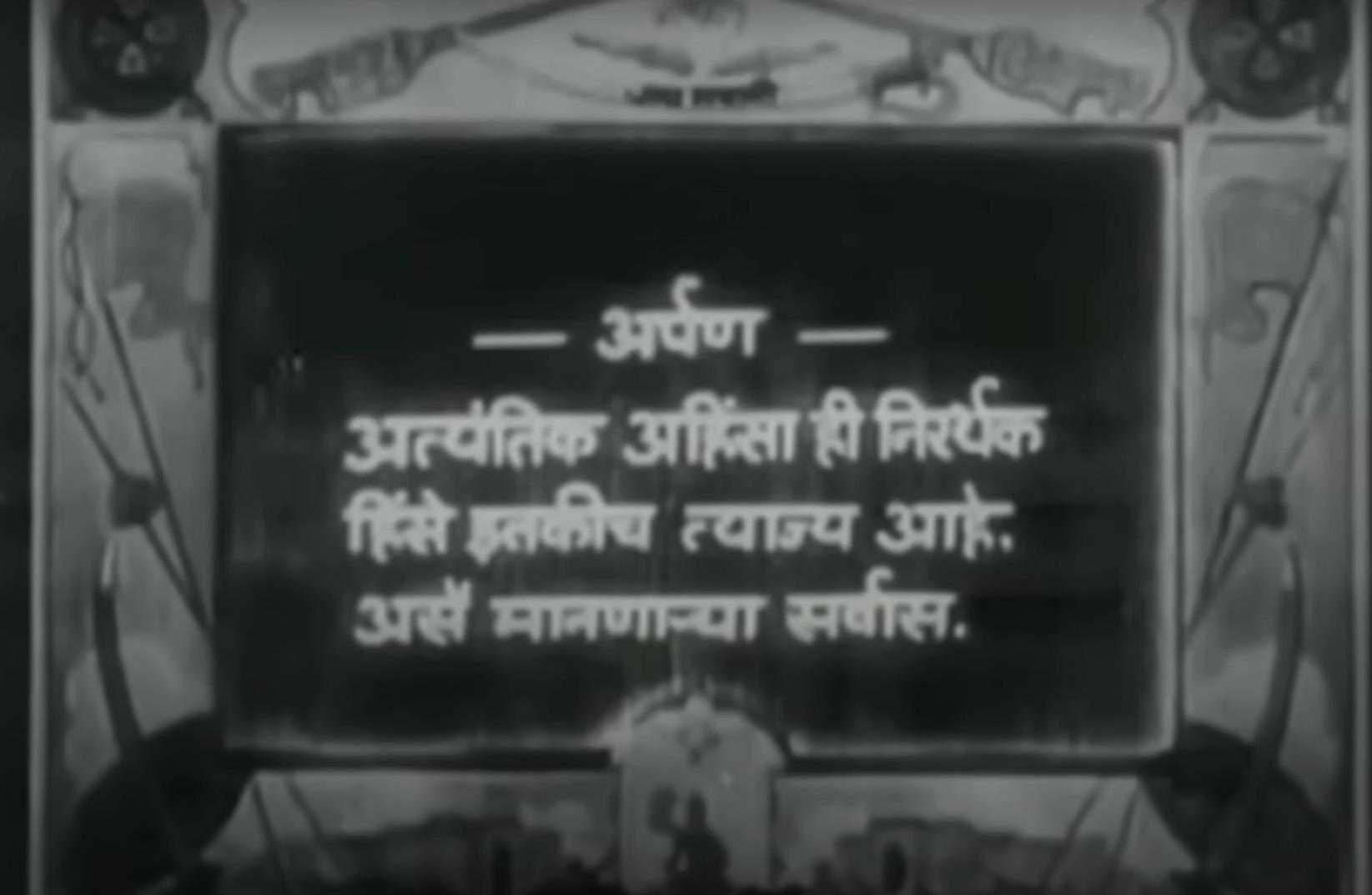

A title card from the film Jai Bhavani (1947) by Jaishankar Danve carries a dedication in Marathi that states “Extreme non-violence is as destructive as meaningless non-violence. To all those who believe so.” (Source: YouTube.)

One of the first movies that unabashedly invoked these ideals and became a sort of template in Marathi cinema was Jai Bhavani, released in 1947, the year of Indian independence and Partition. Directed by Jaishankar Danve, the story and screenplay were written by a veteran filmmaker, Bhalji Pendharkar, who was widely known for his vocal support for RSS and Hindu Mahasabha. This framework largely sidelined the complexities of social and religious diversity within the Maratha polity of the late medieval period. Thus, in the above image, a dedication from the film asserts: “Extreme non-violence is as destructive as meaningless violence. To all those who believe so.” This declaration boldly critiques Gandhian pacifism and challenges prevailing ideas of ahimsa (non-violence), suggesting that blind adherence to non-violence can itself be harmful, especially when confronting oppression. Thus, it reflects a growing assertion of militant nationalism in the late colonial and early post-independence cinematic imagination.

Historical accounts suggest that the Maratha Empire established by Chhatrapati Shivaji was far more complex and inclusive than how it was portrayed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Historians have shown that the empire thrived by drawing support from a wide range of social groups, including various castes and religious groups. Chhatrapati Shivaji, in particular, is remembered for his administrative reforms, promotion of regional language and culture, and efforts to build a broad-based kingdom beyond narrow caste lines. However, later Brahmanical narratives selectively reinterpreted this legacy, particularly reducing Shivaji and Sambhaji to symbols of Hindu resistance against Muslims. This communal framing overlooked the pluralistic and pragmatic nature of their rule, distorting historical memory to serve ideological purposes. Instead, it projected a binary world of noble Hindus, primarily led by Brahmins, versus villainous Muslims. Against this backdrop, films like Chhatrapati Shivaji (1952), Maratha Tituka Melvava (1964) and Raja Shivchatrapati (1974) reinforced this narrow historical vision by presenting Shivaji Maharaj as Go-Brahman Pratipalak (the protector of cows and Brahmins) and surrounding him with an entourage of devout Brahmin mentors such as Ramdas and Dadoji Konddev.

This still from the 1952 Marathi film Chhatrapati Shivaji captures a pivotal moment where Samarth Ramdas delivers a passionate sermon to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, urging him to formally anoint himself as king. (Source: YouTube.)

In Marathi cinema from the 1940s to the 1980s, Samarth Ramdas, the seventeenth-century saint-poet, was often depicted as a revered spiritual guide and intellectual mentor to Chhatrapati Shivaji, emphasising his role in shaping the Maratha Empire’s moral and political vision. Films portrayed him as a Brahmin sage whose teachings inspired Shivaji’s Hindu dharma and resistance against Mughal rule, frequently exaggerating his influence to align with Brahmanical narratives. For instance, in Pawankhind (1956), Ramdas is shown delivering philosophical counsel, reinforcing a Hindu nationalist ethos. These portrayals, while emotionally resonant, oversimplified Maratha history by highlighting the central role of the Brahmin figures, thus marginalising the diverse social groups that supported the empire, as noted in historical records. Similarly, in Chhatrapati Shivaji (1952), directed by Bhalji Pendharkar, a scene depicts Ramdas urging Shivaji to coronate himself and formally establish the Maratha polity, with Shivaji embracing the title of Dharmasevak (servant of dharma), reinforcing a Hindu-centric narrative. In the scene, Ramdas emphasises the divine duty of establishing Swarajya (self-rule) and calls upon Shivaji to embrace kingship not as a personal ambition but as a sacred responsibility to protect dharma and the people. The scene thus reflects the spiritual and ideological foundation of the Maratha polity, portraying Ramdas as both a guide and legitimiser of Shivaji’s rule.

The films of this period not only foregrounded a Brahmanical vision of dharma and kingship but also presented Muslims as scheming, violent and morally corrupt. In Maratha Tituka Melvava, for example, there are vivid laments about the enslavement and trafficking of Hindu women by Muslim rulers. Such narratives have contributed to legitimising contemporary discussions on 'love jihad’ and thereby exacerbating communal tension within society. They consistently presented similar Brahmin-centric stories, without causing much public discomfort as it usually does in contemporary times.

This poignant still from the film Maharani Yesubai (1954) by Bhalji Pendharkar captures a rare domestic moment of introspection, where Chhatrapati Sambhaji guides his young son Ramraya (future Chhatrapati Rajaram) with a deep sense of self-awareness and regret. (Source: YouTube.)

The film Maharani Yesubai (1954) by Bhalji Pendharkar captures a rare domestic moment of introspection, where Chhatrapati Sambhaji guides his young son Ramraya (future Chhatrapati Rajaram) with a deep sense of self-awareness and regret. Seated beside him, Sambhaji praises his wife, Yesubai’s wisdom, telling the child to grow up like her. But when he begins to urge the boy to never become like him, Yesubai interrupts, reflecting both emotional tension and her enduring loyalty. Sambhaji, remembered as a martyr for Hindavi Swaraj, is portrayed here not just as a warrior but as a tragic figure—brave yet often seen as impulsive and misdirected.

Thus, gendered and communal anxieties, frequently projected through stories of temple desecration and forced conversions, became central to the cinematic imagination of the history of the Maratha golden age. Meanwhile, the multi-social character of the Maratha Empire was erased, along with the critical roles played by Muslims, Dalit and Bahujan castes and non-Brahmin soldiers, administrators and intellectuals in the building of the state. This erasure mirrored a broader ideological project to recast history as a moral struggle between Hindu virtue and Muslim villainy while reinforcing caste hierarchies and elite dominance. There is little doubt that such cinematic narratives simplified Maratha history into a Hindu-Muslim binary, amplifying the role of Brahmins while overlooking the contributions of the empire’s socially diverse participants. However, since the 1990s, these portrayals have been increasingly challenged in the public sphere, including aggressive protests by the members of the Maratha caste. In the wake of economic liberalisation heralded in the 1990s, Marathi cinema depicting Maratha history underwent significant changes. Shaped by various influences, it began to shift away from conservative, Brahmin-centric narratives toward more assertive portrayals of heroism of socially diverse groups. However, the Hindu-Muslim binary often remained intact in the cinematic narratives, albeit in a subtle yet pointed form. The following discussion explores Chhaava and the evolving trajectory of Marathi historical cinema since the 1990s in greater detail.

This still from 'Dhanya Te Santaji Dhanaji' (1968) shows a scene where Chhatrapati Sambhaji, after his arrest, confronts Aurangzeb and reflects on his perceived failures. Such portrayals have been criticised by Maratha and non-Brahmin groups in Maharashtra as historically biased, particularly after the 1990s.

To learn more about films exploring identity politics in Maharashtra, read Ankan Kazi's essay on Akshay Indikar's Udaharanarth Nemade (2016), Sucheta Chakraborty's reflections on Jayant Somalkar's Sthal (2023) and Akash Sarraf's observations on Mani Ratnam's Bombay (1995).

To learn more about intersections of caste and communalism, read Vishal Singh Deo's essays on majoritarianism in the agrarian north and capitulation of peasant caste leaders to far-right politics after the 1990s.