In the Wake of Remembering: Memories of the 1992 Burnsall Strike

1992: In the steely, industrial town of Smethwick, Birmingham, nineteen workers—predominantly Punjabi women—walked out of the Burnsall factory for what turned out to be a year-long resistance movement for equal pay, health and safety measures, and union recognition. The workers did not see their demands met, but the memory of the Burnsall Strike—fragmentary as it may be—continues to hold lessons for international workers’ solidarity.

Screened at the 2025 Kolkata People’s Film Festival, Sara Saini’s In the Wake of Remembering (2024) reflects upon three women’s memories of the strike as it pieces together the political, personal and domestic lives of South Asian women against the history of workers’ struggles in the UK. In this interview with ASAP | art, Saini talks about the importance of the act of remembering the strike through her film.

The Burnsall Strikers, as photographed by Kevin Hayes, 1992-93.

Kshiraja (K): What was the impetus to make In the Wake of Remembering? Why this strike? Why now?

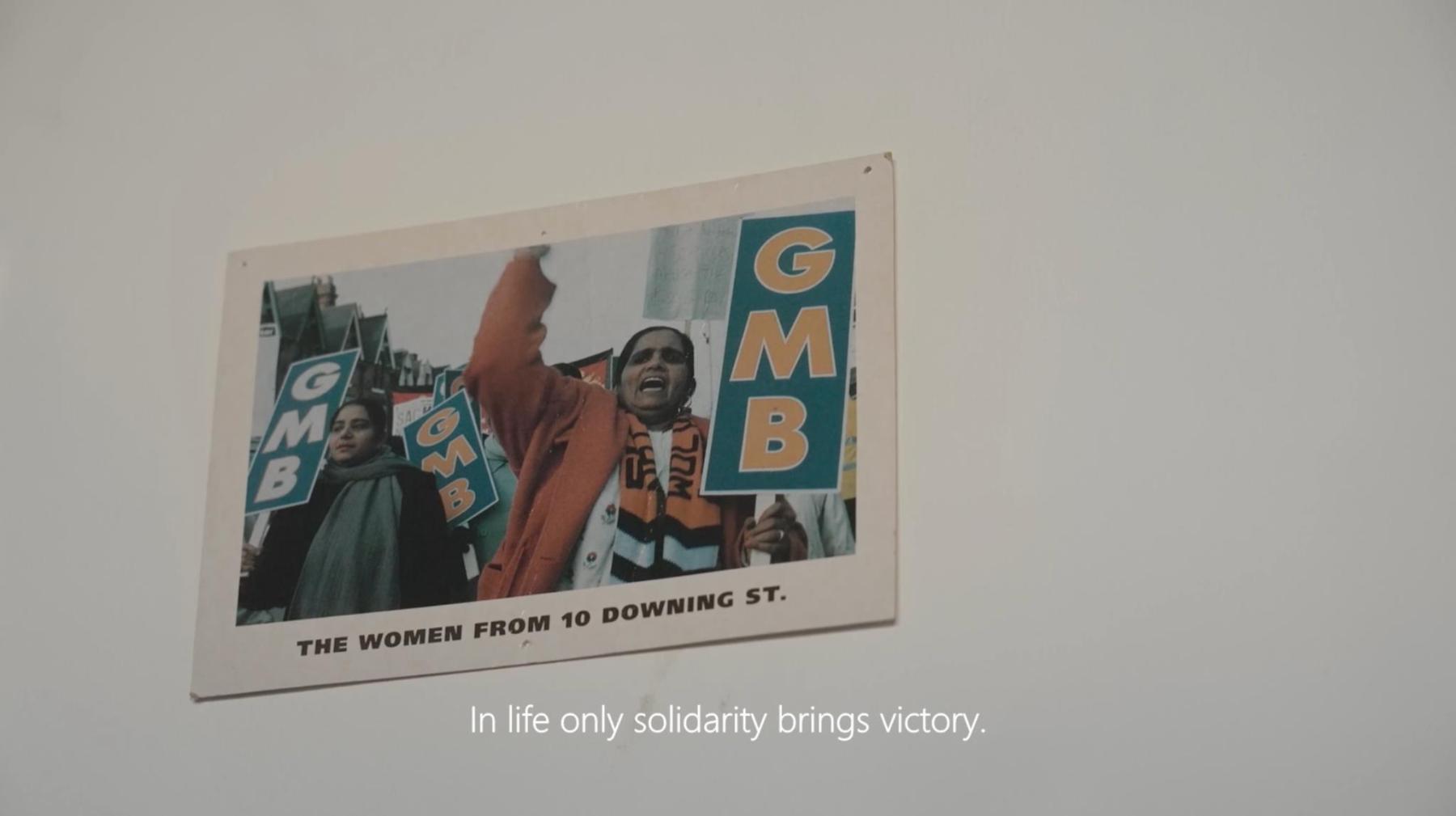

Sara Saini (SS): I had just moved to the UK and the experience of migration was subconsciously on my mind. I found it really hard to make films in this context because it was so new to me. I could not relate to anything here, and I realised that the only way I could make something honestly was if I make something that I am going through at the moment. My partner shared with me this Channel 4 documentary called The Women of 10 Downing Street (a 1993 documentary by Anne-Marie Sweeney, which was filmed during the course of the Burnsall strike), and I remember watching it and just crying. Something about the way (the women) looked, something about their expressions and that they were wearing a saree or a salwar kameez and a coat over, made me feel like I knew them.

Detail from a painting from the exhibition Keep on Moving, by the late Comrade Sarbjit Johal, of the South Asia Solidarity Group.

A lot of them were the sole earning members of their families because of the recession. Their husbands, who were also factory workers, had lost their jobs. They were working sixteen hours a day. I felt that I needed to find them. So I spoke to people from the area. I also found newspaper clippings which reported the death of one of the strikers—Surinder Bassi, who was at the forefront of the strike. I saw the street name and I went to Wolverhampton, where I doorstepped, but there was no one left from that time. I went to the Birmingham city archive and searched every single piece of paper that existed about the strike, but I could not find their names. How is it that this happened here, in the ’90s, and there is so little information about it? I could not fathom the idea.

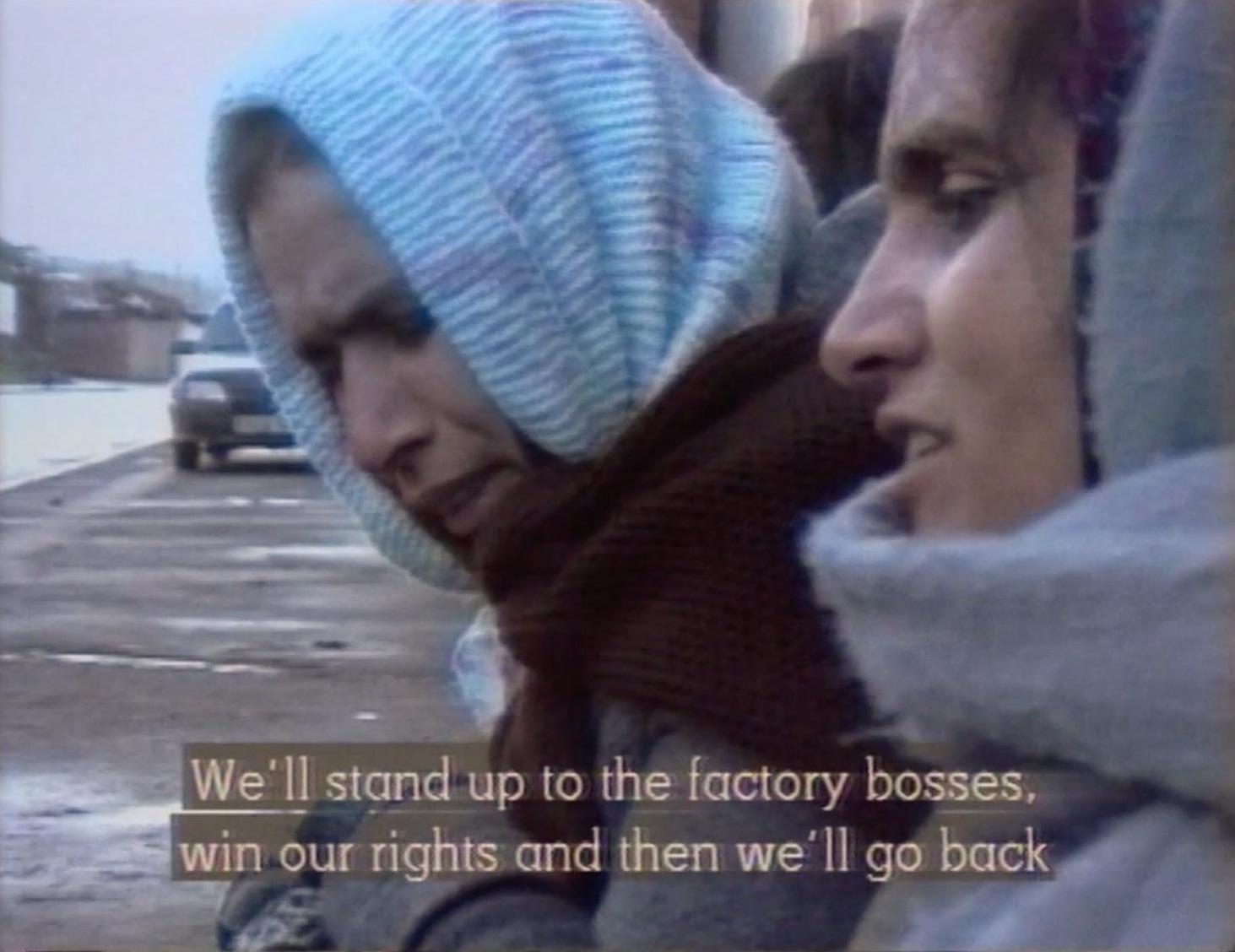

It is not only inspiring, but it also serves as a roadmap for right now—about how to protest and how to bring your domestic lives into your protest lives. They are not separate—the women would stand outside and knit. They were not protesting like men; they were protesting like women. Nineteen women, protesting every single day for one year in the cold—not speaking English, but dealing with the police, the factory owners and the union representatives, all of whom were white men. The harder I found it to research, the more I wanted to make the film. I just felt it in my bones.

Navtej Purewal revisits a protest song written for the Burnsall Strike in 1993.

K: The film is structured like a memory or a recollection as opposed to a traditional documentary. What prompted that structure, which flows in-and-out from different narratives?

SS: It did not feel like I was learning (about the strike) in a chronological order. It was like a little snippet here, a little history there, and I had to make sense of it. I think that reflected in the edit. The idea of making the film was never to retell the story of the Burnsall Strike, it was about the importance of remembering strikes like this one. The biggest tool of oppression is erasure. How is it that all of the libraries and archives in Palestine were destroyed? Because if you erase the history of an entire community or the history of their struggle, they have no framework to stand on. The film is not really about facts or events, rather it is more about the importance and the diverse ways of remembering. And how we remember is not chronological.

We remember in moments; we remember with smell or with little images. The last image, of the woman walking—that is how I remember standing on the street while filming. It is the same spot where the strike took place. I went there to film, and I could hear the strikers’ chants somewhere. That is how I wanted to treat it, because for me, the process was so layered and internal, something from my own Punjabi identity that I never thought too much about.

Strikers brave the harsh winter at the protest site. (Still from Anne-Marie Sweeney’s Channel 4 documentary, The Women of 10 Downing Street. 1992-93.)

K: How did you navigate the idea of remembering what was not so much a ‘victory’ as much as what might be termed a ‘loss’ or a ‘failed struggle’?

SS: At the time, I thought, what strike is ever a victory? It is like what Sarbjit (Johal) said in the film—who wants to do this? Who wants to stand in the cold every day? You do it because you have to. The fact that their demands were not met did not mean that their striking was useless. They still spent a year striking, and when we remember them, we think of their strength. Even when you watch the original documentary, you do not feel like they lost. You feel like they won because they did it. It became a national movement, which is why it was also shut down because even the union felt threatened.

When the workers started the first day of the strike, they were all already fired. But what was so special about the Burnsall Strike was that it did not remain just the nineteen people. There were cross-solidarity movements. There were women against pit closures, women who were protesting about something completely different, who came together and stood in the cold with the Burnsall strikers, who in turn would go for those protests and stand in solidarity. Artists, poets, rappers, academics and students all came together for this localised movement. That is definitely a success. The strikers knew it was not about winning anyway. It was about exercising agency. If you are able to exercise agency, if you are given that space, you are given help and support—then I think that is pretty special.

To learn more about forms of documentation exploring questions of labour rights and gender, read Nithya K’s essay on fisherwomen's struggle for dignity in Puducherry and Kamayani Sharma’s reflections on Megha Acharya’s Meelon Dur (2023). Also read Sumaiya Mustafa’s two-part essay on Samuvel Arputharaj’s Manjolai (2024) and Gulmehar Dhillon’s observations on Amirtharaj Stephen’s photographs of the protests against the Koodankulam Nuclear Power Plant.

All images are stills from In the Wake of Remembering (2024) by Sara Saini. Images courtesy of the director.