On Publishing at the Chennai Photo Biennale 2025

Amidst the framed photographs displayed at the fourth edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale were photobooks bringing together images that spoke of intimacy and sensoriality. What happens when a photograph is not framed and exhibited? What do we feel when we encounter it in the form of a book? Can how we see an image change the way we perceive it?

Ann Griffin is a Swiss graphic designer who works primarily with photobooks. Anshika Varma is a photographer, curator and founder of Offset Projects in New Delhi, India. Indu Antony is a multidisciplinary artist based out of Bengaluru and Kerala, who uses photobooks as part of her work. They offer insights into the many approaches to photobook making, the inherent challenges of the process and their own unique perspectives on the form as an entry point to experience community, to subvert conventional notions of what a photobook is and to reimagine what it could be.

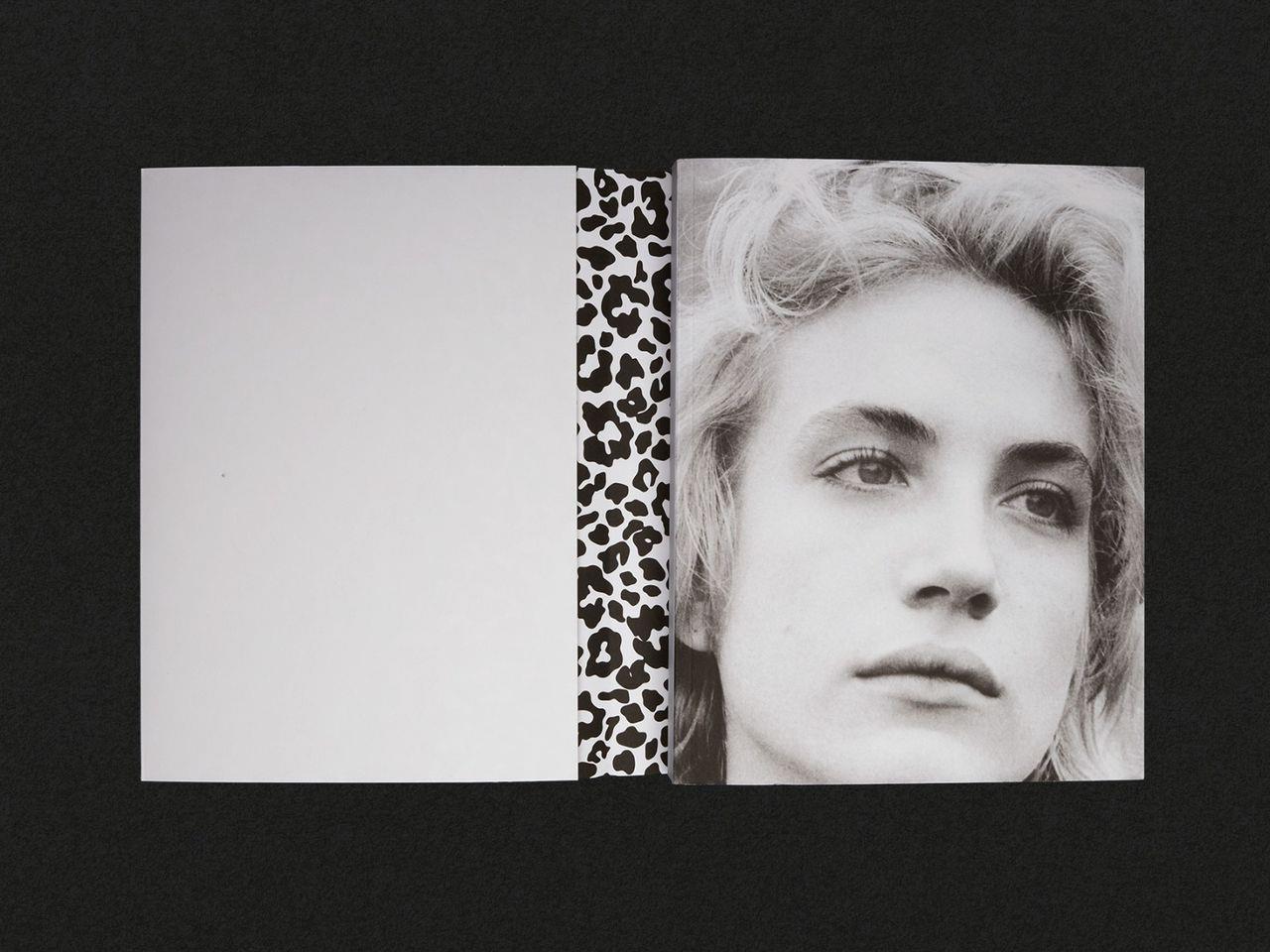

Cover of a book designed by Ann Griffin. (Image courtesy of Ann Griffin.)

Anoushka Mathews (AM): In what ways does designing a book with photographs vary from a photo exhibition? As a graphic designer, what draws you to photobook making, and what are other aspects which are more challenging?

Ann Griffin: I enjoy exhibitions a lot, but I do not have experience in curating or setting up shows. A photobook is a completely different experience. I make photobooks because I am interested in the stories photographers have to tell. There is something beautiful about turning a sequence of photographs into a physical object—something you can hold, carry, keep and return to. It happens in your hands, in your time. The book asks you to turn the pages—but how, when and in what order is up to you. The exhibition is designed to make the viewer see and experience in a certain way.

I try to create books that make you feel that story—through the materials, structure and even the silence between images. I see the book not just as a container but as part of the narrative itself. The design should serve the story, not overshadow it. I am not interested in making something new or different for the sake of it. I am interested in making books that make sense—where I feel the story needs to be told, where the artist has something to say. If the story is important, it is a book worth making.

Spread from a book designed by Ann Griffin. (Image courtesy of Ann Griffin.)

Making a book is such a long, expensive and intensive process that many projects never make it to the end. So it is important to be realistic and only make books I truly believe in.

The real challenges are not in the design process—they are in the bookmaking world. There is no money and no one can pay for the time it takes to make a truly good book. The entire ecosystem—publishers, distributors, funding, printing and selling—is complex and only in a very few exceptions is it sustainable. Books happen only because of a bunch of highly motivated people. It is love and passion, not a business. It is sad because there is a high interest in photobooks but nobody can really make a living from it.

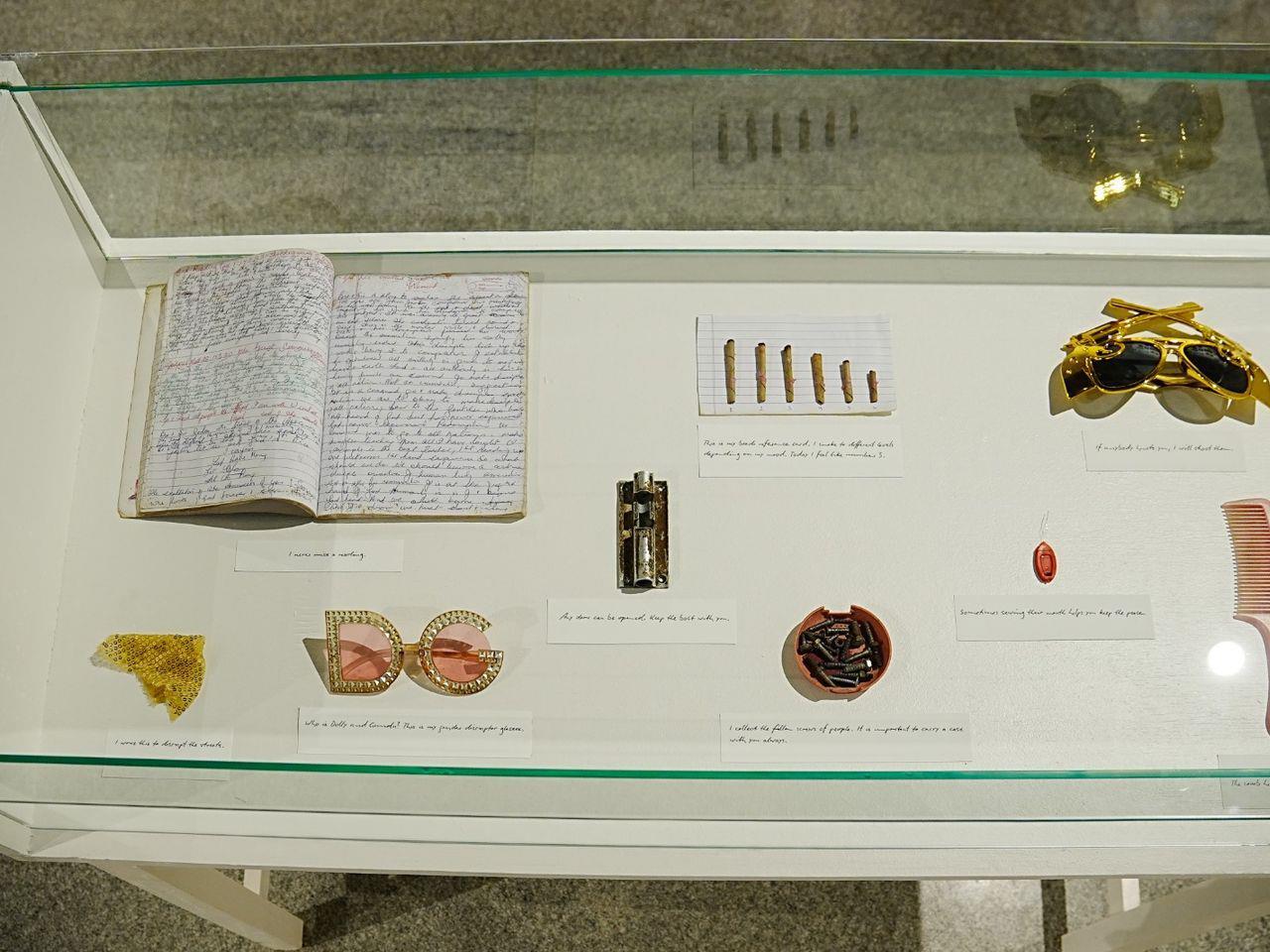

Installation view of Cecilia’ed by Indu Antony at the Chennai Photo Biennale. (Image courtesy of Indu Antony.)

AM: For your work Cecilia’ed, which was exhibited at CPB earlier this year, why did you choose to include a photobook along with the other images displayed on the wall? In what ways do you incorporate sensory elements and analogue visual language from photo albums in your work?

Indu Antony: I do not think every project should be a photobook. I think only if the project demands a need for that intimacy of a book—to be held and looked at—should it be there. In my work with Cecilia, we have more than 100 images, but CPB had a wall where only four could fit. And it was very important for me to showcase that it is more than a decade-long project and for the audience to get an idea of the years and years that we have spent together taking images and having fun with it.

I felt it was important to have a book format so people can read through her comments and her idea of dressing up and things like that. That is exactly why I made the book. Also, it continues to be accessible even after a show closes. And I felt that for her, as a character, how much of it do we get to see from looking at a very flat image on the wall? Most of my other work, like my first book, remains only as a book and does not jump out of the book to an exhibition later.

I am someone who embraces any medium. My second book explored the olfactory medium. It had two-millilitre vials of different smells of Bengaluru, which you could open and put on different parts of the book, and you then smell it. So text is a different format of one of the senses. You can speak it out or you can read it out in your mind. So I love to engage with more and more senses, even in my work with photobooks.

Installation view of Cecilia’ed by Indu Antony at the Chennai Photo Biennale. (Image courtesy of Indu Antony.)

The old analogue photographers here in Bengaluru have a certain visual language. So I remember, while working with one of the local photographers to make a photo album, he had photoshopped Cecilia going to Sikkim and dancing. And there is an image of her sitting on a Yamaha or some kind of a bike—again photoshopped. And that was his way of representing her like a hero. For me, it was important for that to be a part of the whole project as well.

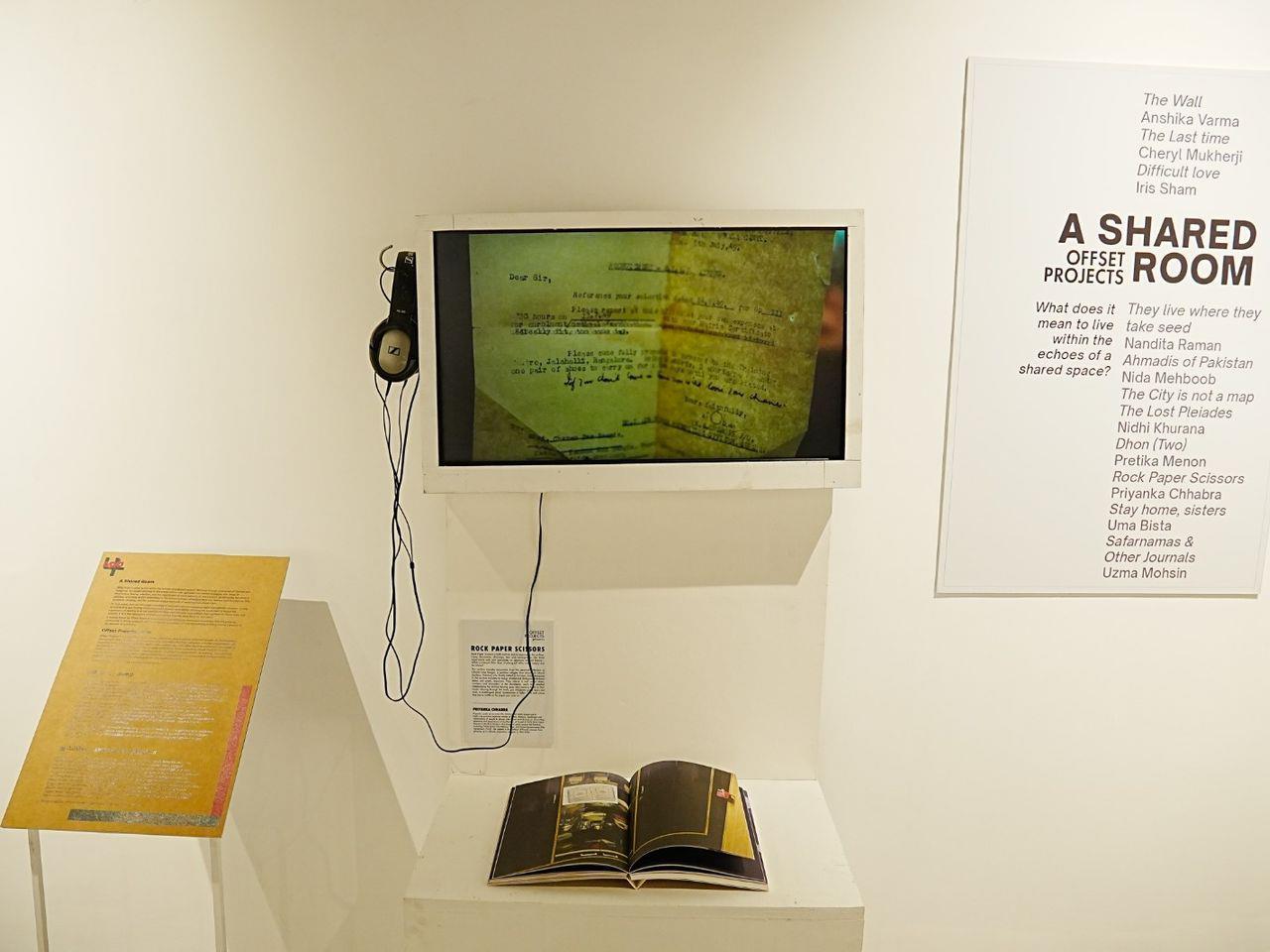

Installation view of A Shared Room by Offset Projects displaying book as video at the Chennai Photo Biennale. (Image courtesy of Anshika Varma.)

AM: What was A Shared Room, and how did it bring together different imaginations of a photobook? Can you talk about the idea of using the photobook as a way for artists from different mediums to engage, speak to each other and build community?

Anshika Varma: It took off when we realised that they were different manifestations and iterations of exhibits that we were doing around the photobook. The murmurs of the pages that are brought to life when they are held in someone’s hand or have an eye looking at it.

A Shared Room was a showcase of ten artists using different formats. The Shared Room is a program that Offset runs and this was an iteration of that program. We had the book as a sculpture; we had the book as a video; we had the book as an ideating desk; the book as a cartographic experience and so on. We had books that emerged from the making of a film, my own work, where we have a mix of photography and drawing in printmaking and natural pigment making. A Shared Room was a way of showcasing works as they grow, as they emerge and even as they close.

In one of the books by Iris Sham, we actually worked on an iteration where we expanded from it and explored the iterative freedom in bookmaking. She literally tore the entire book and turned it into a sculptural piece in the form of a bowl of rice. Her work explores the difficult relationship she shares with her mother, and the rice bowl was inspired by her mother’s constant concern about her eating.

Installation view of A Shared Room by Offset Projects displaying rice bowl made with a torn book by Iris Sham. (Image courtesy of Anshika Varma.)

Guftgu, which was part of A Shared Room and also the first publication for Offset Projects, brought together works of multiple artists, allowing for the book to become a shared space. It also challenges the homogenising of South Asian artists by bringing together different voices, distinct practices and manifestations in photography from the region. And so the book is not only having a conversation with the world but the curated artists are also having a conversation with each other.

To learn more about the recently concluded edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, read Kamayani Sharma’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore process; Mallika Visvanathan’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore memory, with artists whose practices explore archives and with the curators of the primary shows; Vishal George’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore urban landscapes and with artists whose practices explore the theme of labour; and Anoushka Antonnette Mathews' short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of mental health and neurodivergence and with artists whose practices explore themes of bodies and landscapes.