Flickering Lights: On Hope and Resilience in Tora

Waiting.

Screened at the 2025 Kolkata People’s Film Festival, Flickering Lights (2023), a feature-length documentary film made by Anupama Srinivasan and Anirban Dutta over the course of seven years, begins with illustrations of a house made of white lines drawn on a live-image of a textured old wall, which give us the context of the film. A village named Tora, in Ukhrul district, sits at the Indo-Myanmar border in Manipur; it is home to the Naga community, which has been at odds with the Indian State since the 1940s. Tora lacks basic infrastructure such as electricity, schools and roads. The narrative unravels around the hopes and doubts of the village residents who have been promised electricity several times, but are still waiting for it to arrive, as if waiting for Godot.

From the opening scene, the film moves to a shot of the moon and pans down to village residents, in jeans and tops/shirts, doing a carefully coordinated five-step movement traditional dance with electronic torches in their hands. This evocative sequence sets up the mise-en-scene of the film, which observes but also comments on the Nagas of Tora and their everyday attempts at survival. Its dichotomous framing and the simultaneous realities that exist within the time and space of Tora signals how the village does not easily render itself to binaries of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity.’ The darkness of the night then cuts to the almost blinding brightness of sunlight, and to a long shot of male workers walking in the field carrying heavy bags on their backs. This is followed by women working in the fields, standing with their legs immersed in the black muddy water, as they talk about their back pains. We then see a man making tea in a small shack at the edge of the fields, accompanied by a woman. He is then seen closer, carrying the large sack of produce on his back. This sequence allows for life and the world of Tora to unravel on the screen, and introduces the two characters whose journey as a family will unfold parallel to the community’s journey in the filmic narrative. A couple, they are struggling to pay the fees of their children who are in a boarding school. Later, they appear in a scene where many other village residents are scampering into the truck; they are helping with the goods and bidding the truck goodbye, whereas far off in a distance on a slope, the illegible figure of a woman watches the camera. The filmmakers, Srinivas and Dutta, commented on how they arrived at the lensing of the film, using a 50mm block lens, so as to not isolate individuals or characters from context.

Grandpa listening to the news on his radio.

We are ushered into darkness with just a torch, with the couple now arranging the sacks, keeping the tithes aside for the Church. This interplay or juxtaposition of day and night, light and darkness continues through the film. Exquisitely shot by Srinivasan, Vandita Jain and Mrinmoy Mondal and edited by Srinivasan herself, the next scene seems like it is extending from the very same mud road on which the truck left, the truck sound still trailing in, and we see an old man with a stick and a cat. He turns to look at the camera and walks into his shack-like home, with the cat tailing on. He sits by the door with a transistor in his lap, the cat his co-listener inside the house, as the news announces attempts at peace negotiations with the State in the region.

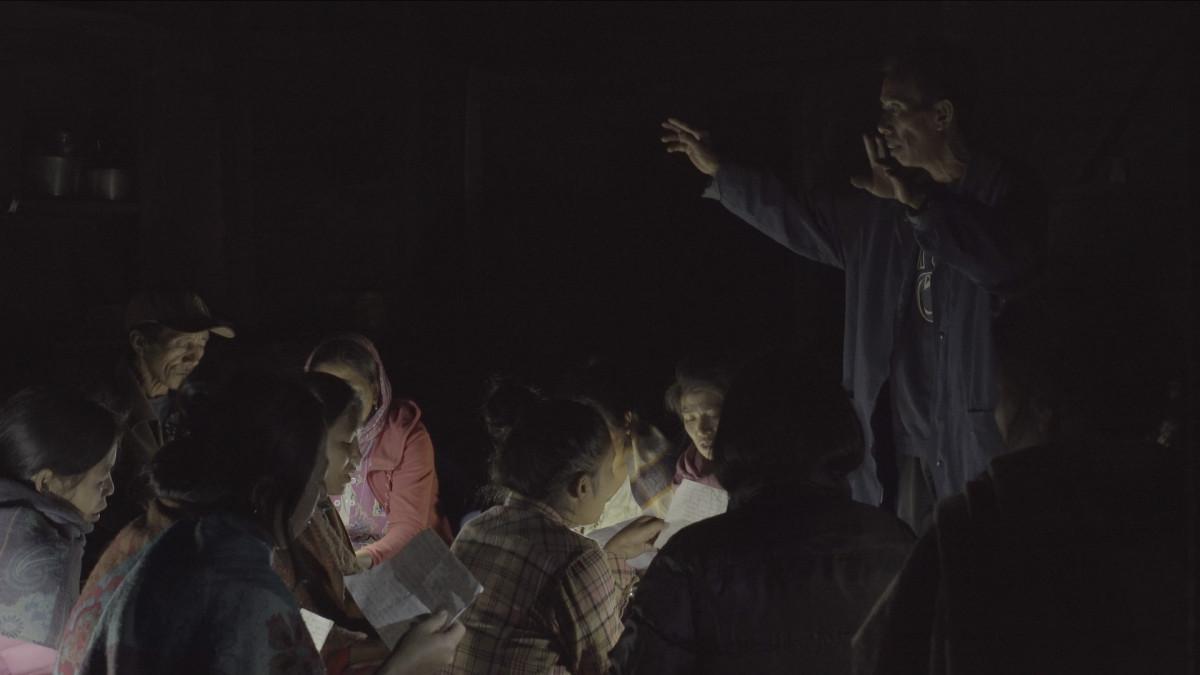

The old man, or Grandpa—as Srinivasan referred to him in a conversation with this author—watches as young men dig holes for electric poles. Their labour, with rudimentary tools, is exhausting. Grandpa, we realise, was a Naga insurgent and was part of the resistance army. He is finally back ‘home’ in his old age and dreams of light to walk around the small shack with his cat. The couple dreams of a better life for their children. The wife aspires to own a refrigerator in their tiny shop so as to make and sell ice candies and ice creams, so that she can afford to pay the school fees of her children. Thus, in terms of narrative elements, the film oscillates between the physical labour of trying to bring electricity to the village and the lives of the different people. The film shows us the rhythms of how the Naga people there have slowly woven their lives, even without light. For instance, in one scene, a woman weaves the most exquisite Naga shawls in traditional patterns, working late into the night even without light. She says that is how she was able to raise her kids. Despite all the failed promises, they have managed to make their own individual lives and a collective life possible in Tora. It signifies their resilience in the face of the everyday. For instance, in a poignant sequence, they rehearse choir songs for the upcoming Christmas season, with torches, barely able to read the lyrics owing to the lack of light, tunes akin to Western church songs, but lyrics in the Naga language. And in fact, the filmmakers commented on how they saw the film as a conversation between image and sound in the terrain.

Singing through the night.

Having conducted a range of workshops and undertaken teaching activities in the region, the filmmakers shared that they have a long association with the community. Dutta grew up in Kolkata and has actively engaged with communities across the North East through participatory workshops and camps since 2005. Srinivasan first visited the region as a tourist in 2003, and her association has persisted to date through teaching assignments and research via NGOs working in the region. The electrification project was taking shape in various parts of Manipur, and Ukhrul—a place they had already visited—was isolated in terms of connectivity. Even though Tora had not yet been visited by the media, and there was resistance to Srinivisan and Dutta—people from “India”—their relationship grew over time. Srinivasan and Dutta lived in the village and gradually, Srinivasan says, she went from being known as “that fat woman with the camera” to “Anupama.”

Scene of men at work.

The filmmakers had imagined their film as building a bridge between the people of Tora—located in Ukhrul district—and the people beyond. Both Dutta and Srinivasan are keenly aware of thin narratives about the region—through the lens of conflict and violence, or HIV, or a complete exoticisation of the region and its people—and they wanted to reflect the region in all its complexity. However, Srinivas and Dutta are clear that this is a story that “we are saying”; it is the filmmakers’ take on this world, but with an investment in truths that emerge from the Nagas.

The film also becomes a rumination on how North-Eastern states exist in relation to the Indian State. It stands as a testament to our inadequate interest and knowledge of the region, evident during the ongoing Manipur killings and its insufficient media coverage. Eventually, with the men of the village labouring in dangerous conditions, flickering lights arrive in the village. The scenes of the collective efforts and strategies of the men who are working to mount an electric pole are evocative. They bring warmth to the audience who are assured that Tora's residents can celebrate at least the next Christmas with lights.

To learn more about Manipur, please read Sukanya Deb’s piece that engages with Rohit Saha’s work with the Extra-Judicial Execution Victim Families Association Manipur (EEVFAM), Veerangana Solanki’s conversation with Rohit Saha on his photobook around the Malom Massacre and Niyati Bhat’s article on Samarth Mahajan’s documentary Borderlands (2021).

All images are stills from Flickering Lights (2023) by Anupama Srinivasan and Anirban Dutta. Images courtesy of the directors.