Partitioned Cinemas: Salma Siddique’s Evacuee Cinema

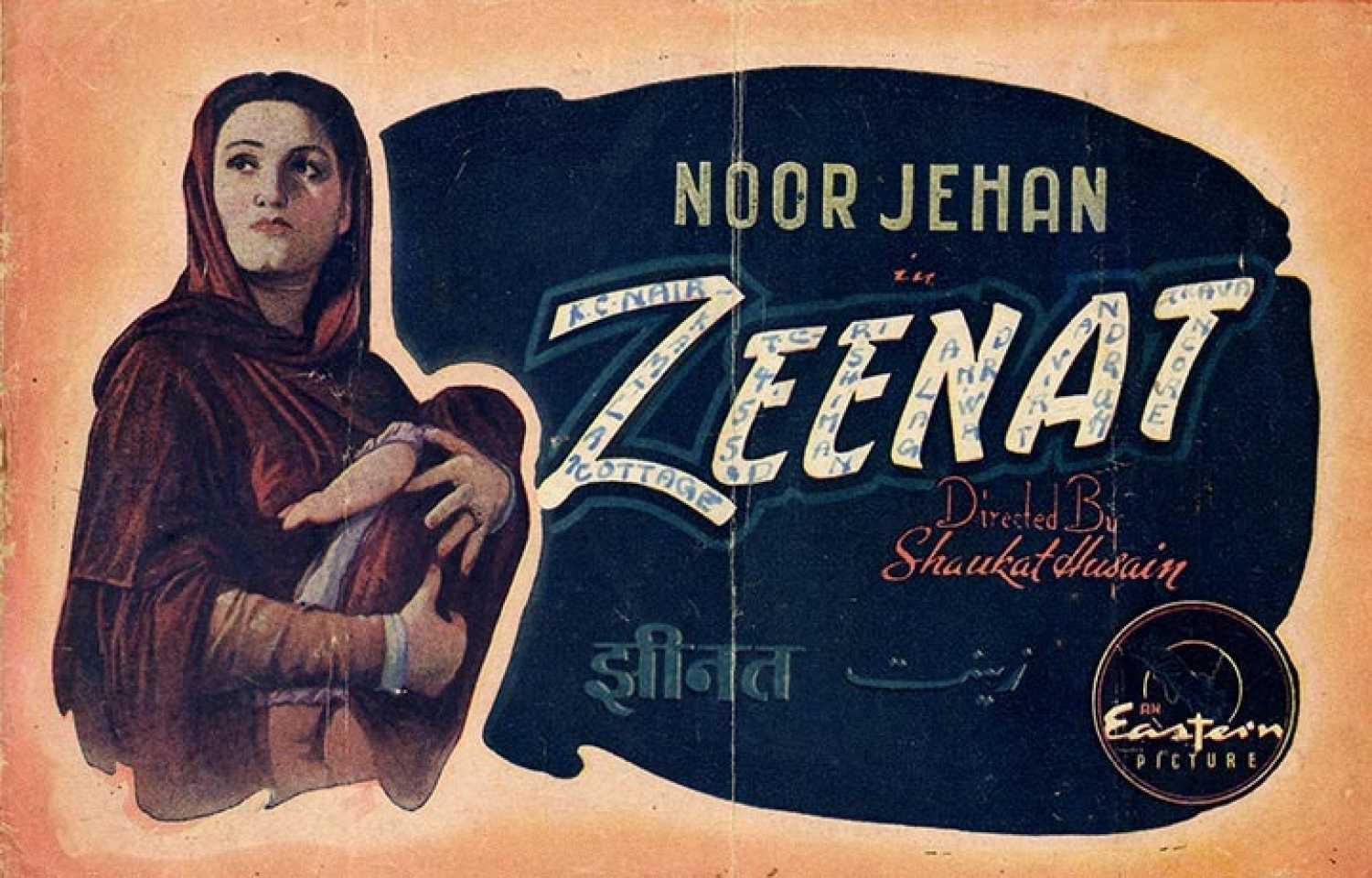

Poster for the film Zeenat (1945), directed by Syed Shaukat Hussain Rizvi and starring Noor Jehan. (Image courtesy of Cinestaan.)

Evacuee Cinema: Bombay and Lahore in Partition Transit, 1940–1960 by Salma Siddique explores the creative energies, production and subsequent circulation of popular cinema to offer fresh insights into Partition, especially as it affected a range of common film personnel in both of those cities. The book is narrated through the careers of such émigré film personnel, as well as through the distinctive genres—such as the colonial-era “all-India” film or the “Muslim social”—along with ancillary ventures that accompanied the aftershocks of partition. Siddique moves beyond arguments about social contingency and political intent to suggest that the cinemas of India and Pakistan must be explored in tandem to uncover the legacy of Partition. It also seeks to undo the “false teleology” of Indian national cinema histories that begin before partition, which compartmentalises film cultures across the subcontinent into national categories to frame the criteria of inclusion or exclusion in continuous narratives of cultural production in either India or Pakistan (and later, Bangladesh). The book points to regional connections across national boundaries and asserts that the creative energies of popular cinema can offer new insights into interconnected histories of partition.

Abdul Rashid Kardar (1904–89), one of the pioneers of Lahore cinema, had studios in Calcutta and Bombay as well. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

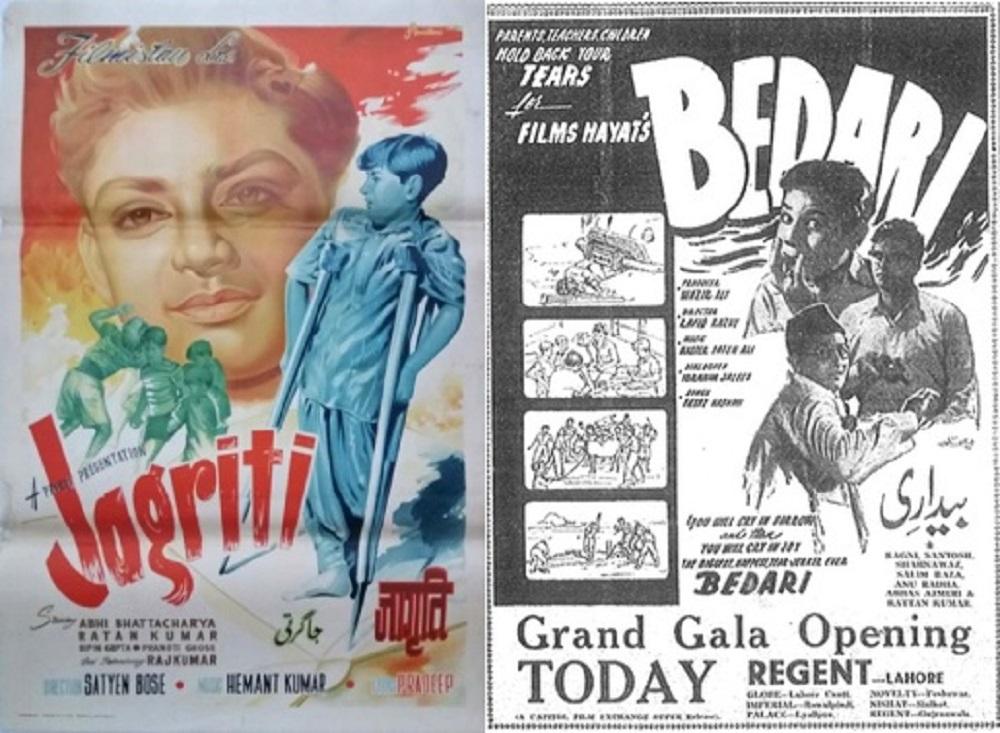

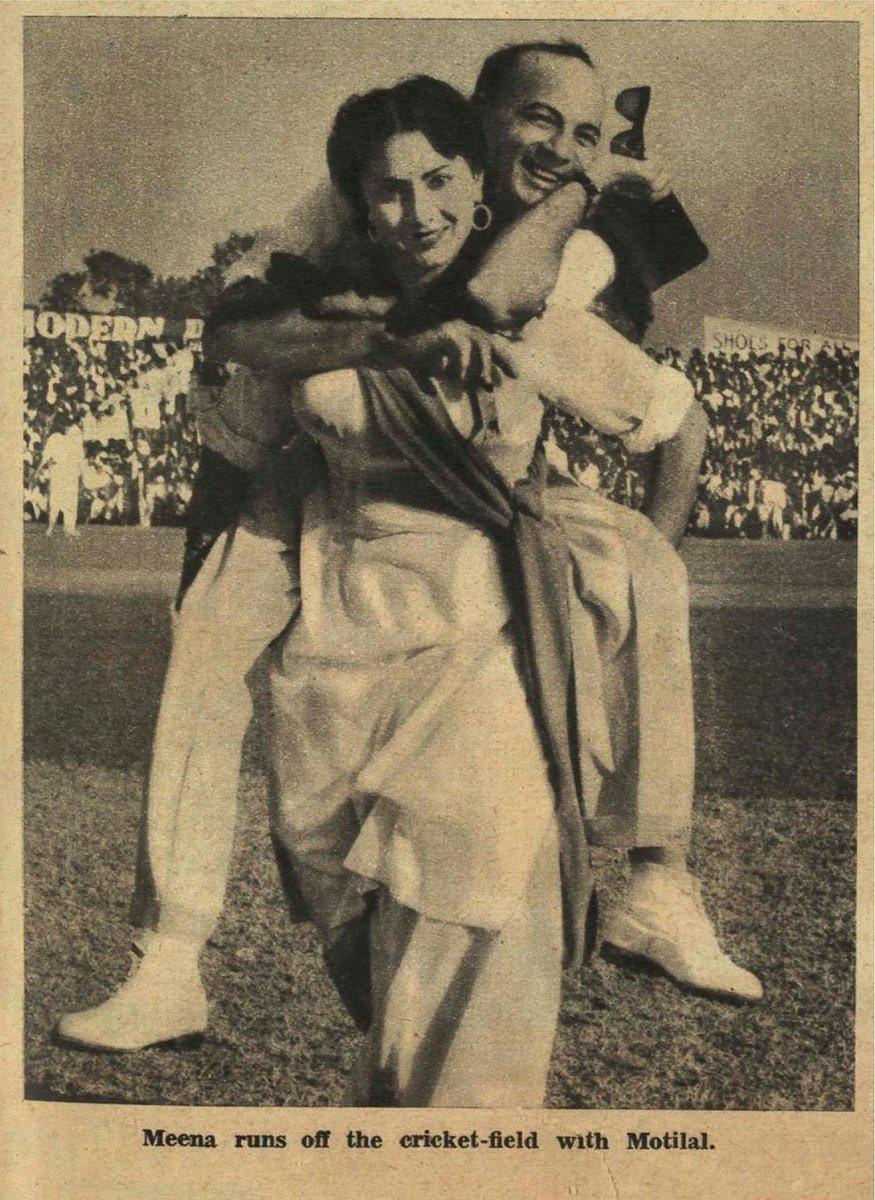

After the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, the term "evacuee properties" referred to properties that were left behind by those who migrated to either India or Pakistan. The Indian government became the custodian of properties left behind by those who migrated to Pakistan and vice versa. The Administration of Evacuee Property Act, 1950, was enacted to regulate the management of these properties. The act provided for the appointment of custodians, the determination of compensation and the disposal of properties. The issue of evacuee properties remains a contentious issue in India and Pakistan. In Siddique’s book, it is paired with the world of cinema so that “evacuee cinema” becomes a dynamic category to narrate a “story of dislodgement involving two sides,” while also denoting the range of studio spaces, properties and technologies that were subjected to similar processes due to their association with “minority filmmakers” and producers after 1947. These included Punjabi filmmakers in Lahore, such as Dalsukh Pancholi and Roop K. Shorey (the first Punjabi film, Heer Ranjha [1932], was made in Lahore). It also included Muslim film personnel such as Ratan Kumar (the famous child star who started his career in Bombay cinema before moving to Pakistan in the 1950s), A.R. Kardar and Meena Shorey, among others.

.webm.jpg)

Still from Roop K. Shorey’s Ek Thi Ladki (1949), starring Meena Shorey. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

As Siddique illustrates through the work of filmmakers and actors like the Shoreys (Roop and Meena), Lahore—which formed a smaller, more uncertain film industry in the 1940s when compared to the more established one in Bombay—was also a site of nascent critique. Here, films were frequently made (especially in Punjabi) that parodied the industrial gravitas of cinematic forms regularly employed by Bombay cinema like the socials or the epics. Siddique therefore revisited popularly discussed genres from the time, like the Muslim social, to which she assigns new, more provocative origin narratives by anchoring them into political expressions of North Indian Ashraf identity. Siddique also focuses on previously little-explored genres, like the screwball comedies being produced that depicted “sublime renderings of partitioned social relations,” continuing a fraught cosmopolitanism in the post-partition years. Another intriguing genre explored is the charbas film in Lahore, which comprised of poorly made imitation films of grander production spectacles from Bombay. The charbas films were attempts at creating makeshift affinities between the new and then-impoverished national film cultures of Lahore post-partition, while accounting for popular taste in Bombay cinema that existed in Pakistan at the time. Figures like Meena Shorey and Ratan Kumar emerge as complex, peripatetic figures, often having to negotiate nascent nationalist narratives being formed on either side of the border after partition, since they both had successful careers in Indian as well as Pakistani cinema.

The Pakistani film Bedari (1956) was directed by Rafiq Rizvi. Starring Ratan Kumar and Meena Shorey, along with others, this musical was Kumar’s first film in Pakistan after he moved to that country following a successful career as a child actor in Bombay cinema. The film was mostly plagiarised from his own earlier Bombay film, Jagriti (1954). (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Due to the unavailability of many such films that were made in Lahore, the author largely reconstructs the relationship between these critical films and Bombay cinema through a reading of extant screenplays and memoirs written by film personnel. These memoirs are themselves complex texts, as they often display cracks between memory and the demands of the present when they were written (often many decades later). Some either exaggerate the secularism of the Bombay or Lahore film industries in the 1940s, while others emphasise the impossibility of collaboration between Hindu and Muslim film personnel. The height of animosity in the 1940s was visible when partition became an entrenched vision of political (and ideological) movements, spearheaded by major parties like the Muslim League and the Congress, and the suggestion that it was not only inevitable but also desirable for continued expressions of progress and cultural sovereignty for both the communities. Producers and film personnel were often partisan, taking sides according to their political beliefs and acting upon them by producing narratives in Bombay as well as Lahore. Film journalists like Baburao Patel, who ran Filmindia, also practiced exclusive forms of communalism that kept a check on perceived slights to India’s Hindu cultural dominance.

Meena Shorey, dubbed the “droll queen” by film journalists, was frequently used in publicity stills to highlight her non-normative body and comedic adventures—in extension of her screen personalities. (Image courtesy of Filmfare, National Film Archives of India, Pune, and Salma Siddique.)

For those looking to expand their understanding of the mechanics around Partition’s impact on Bombay and Lahore cinema, especially through the networked narratives of exchanges between filmmakers, stars and producers, it is hard to imagine a better place to begin than Siddique’s wide-ranging history.

To learn more about scholarly work on early Bombay cinema, revisit Ketaki Varma in conversation with Debashree Mukherjee on her book Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City. Also read Ketaki Varma’s reflection on the archiving of cinema histories through lobby cards and Najrin Islam’s conversation with Anuj Malhotra on the Garga Archives as an alternative archival project.