Subject, Form and Process: In Conversation with Prasiit Sthapit

Nepali artist Prasiit Sthapit recently received the Asia Arts Future Award (South Asia), which recognises emerging talents from the subcontinent who work with the region’s socio-political landscape, cultural histories and lived experiences, connecting with audiences globally. Based in Kathmandu, Sthapit is associated with photo.circle, a platform for photography in Nepal, and is the director of Fuzzscape, a multimedia music documentary project. In 2016, he received the Magnum Emergency Fund Grant and attended the World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass. The artist’s growing oeuvre traverses a range of difficult questions that haunt Nepal’s modern political history. In this conversation, he shares how he developed his documentary photography practice by following his curiosity and the processes that contributed to his varied visual language.

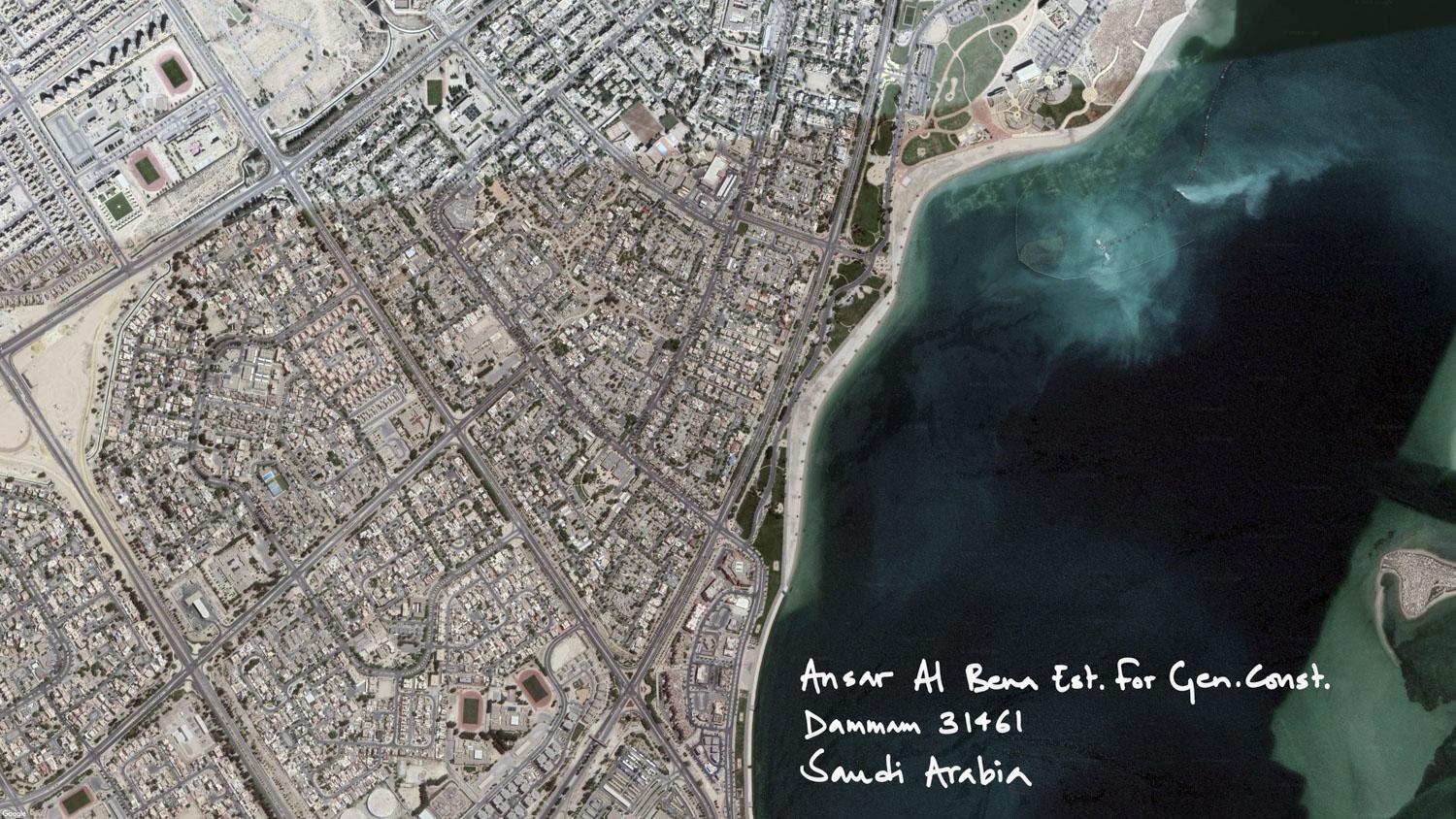

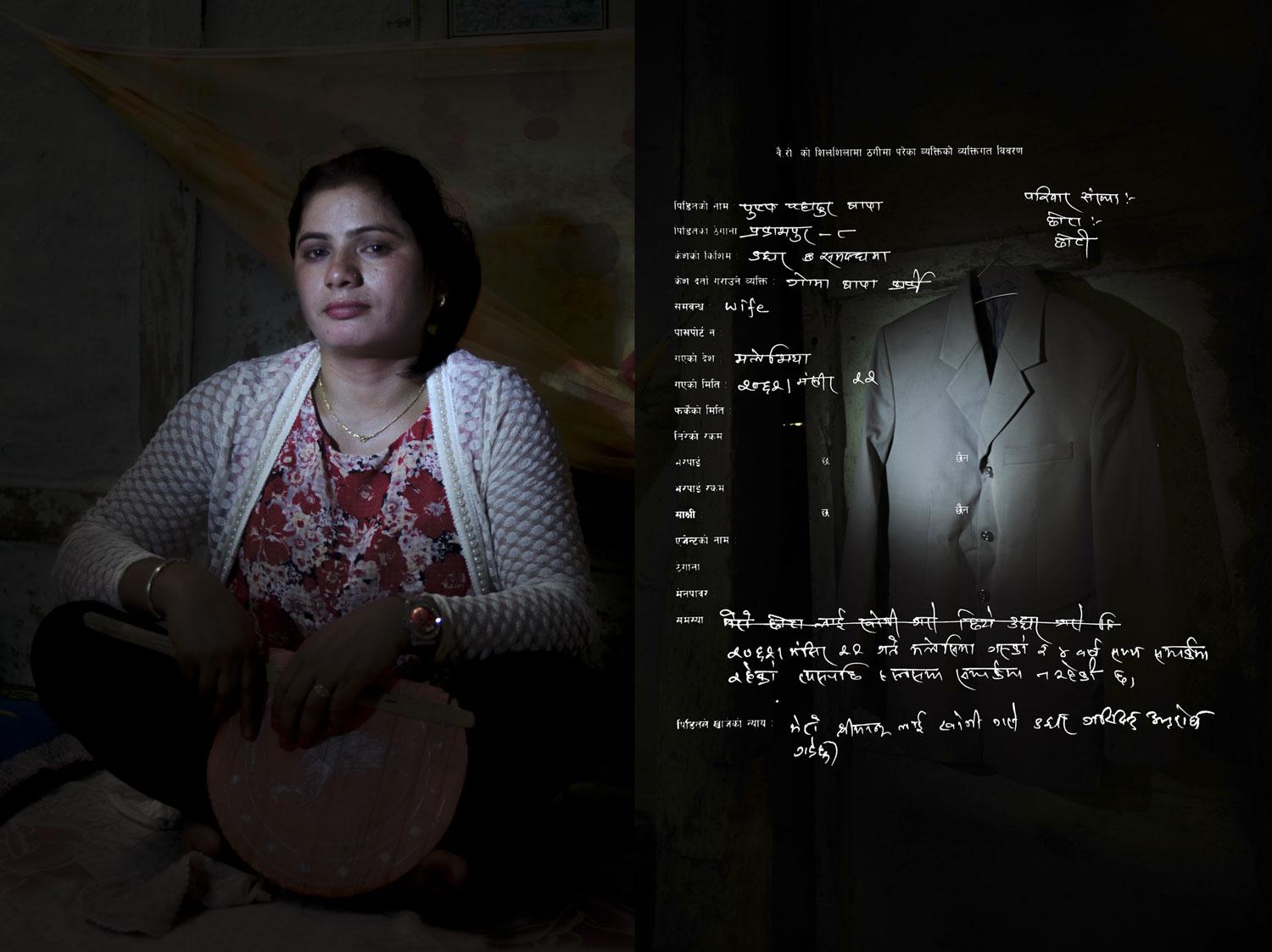

From the series The Mysterious Case of Pushpa and Others (2015-2016).

Santasil Mallik (SM): Congratulations on winning the Asia Arts Future Award! Can you tell us about how you came to documentary photography as a practice?

Prasiit Sthapit (PS): Photography happened to me. My father owned a photo frame shop in the centre of the city. So, as a child, I used to go there whenever I had breaks from school. I used to hang around, play with little pieces of wood and see a lot of photographs—mostly family photographs. I would imagine the lives of these people and make up stories. That was my early inspiration. I also specifically remember one incident, when I was in the fifth grade or earlier, which was the first time that cable television came to my home. Earlier, it was just the national Nepal Television channel. One morning, my dad woke me up, switched on the television, and I saw dolphins swimming on the Discovery Channel. That struck me as incredible. I thought I would be a wildlife photographer and then later decided on war photography.

Gradually, my interest shifted to documentary photography. Initially, I wanted to be a photojournalist, which is why I went to journalism school in India. After three years of pursuing a journalism course at Manipal University, I learned that I did not want to be a journalist. Then, through workshops that I did with photo.circle I got introduced to documentary photography, a form and approach I was not aware of before.

From the series The Mysterious Case of Pushpa and Others (2015-2016).

SM: Certain thematic strands are recurrent in your work, like geopolitical and ethnic conflict in Change of Course and The New Silk Road. Then there is your involvement with traumatic histories, be it personal or political, especially in works like Red is the Colour of Spring and The Mysterious Case of Pushpa and Others. How do you arrive at these thematic intersections? When does something become a documentary subject for you?

PS: For me, it is mostly about curiosity—about things that provoke me to learn more about them. If my curiosity is satiated by something I can read or watch, I do not pursue it further. Why should I? Because it has already been spoken about and, in most cases, much better than I could. For example, we have been hearing about the Susta region since childhood. We knew that Nepal has a tumultuous political history. Every opposition—in order to rile up the masses—would bring up the issue of Susta and Nepal’s inefficient response to the proverbial Big Brother India. The issue has been in the political mainstream for a long time. Like everyone else, I had always heard about it in the newspapers, through television, etc. But I never knew what kind of people lived there or how its geography was. So that is where my project, Change of Course, began.

From the series Change of Course (2012-2018).

The same holds true with my fascination for the revolution, more so because my grandfather was a communist sympathiser. There was very little I could gather to read concerning the heartland of the communist movement, like Rolpa and Rukum. I wanted to learn beyond the available research materials, to revisit those places and interact with the people. My ongoing work, Moonsongs for Earth, is also about the revolution, but specifically through music. Since childhood, I have been really into progressive and folk music. Looking at the revolution through the lens of music is quite rewarding. I became fascinated with how it played a major role in the revolution, bringing people together and harnessing a transformative power. Their dream was to change the world, and a gesture like that can influence so many of us.

Moonsongs for Earth.

SM: Your projects also take different forms and visual grammar. The high contrast, dramatically composed images we see in The New Silk Road are very different from the language of images in Change of Course, for example, which has a washed out, low contrast approach. How do you decide on or develop your form? What does that conversation look like?

PS: It is a very slow and process-based exercise. For Change of Course, I was initially working with high contrast images with dynamic compositions, influenced by the likes of Philip Blenkinsop. Indeed, he remains one of my mentors. Susta is a disputed land, a region of political tensions, which is why I tried to work with gritty, hard-hitting aesthetics. But as I started returning to the place, talking to the people, and immersing myself there time and again, my process slowed down. Sometimes, I was just living in the village, not even taking out my camera for days. I gradually felt that Susta was in a limbo, an island of its own equally cut off from Nepal and India—even though it is surrounded by the latter on three sides. I wanted to highlight the sense of a void in the images, resulting in a more washed out feeling of suspended time. It was also through the mentorship of photographers like Sohrab Hura, Munem Wasif and others that my approach to Susta gradually developed to its current form.

Similarly, I tried to apply this aesthetic approach to The Mysterious Case of Pushpa and Others, but it did not work. It is also the landscape that guides me towards a style. This work centred around the hills of Nepal, and my earlier style was not working here. Therefore, out of frustration, I devised the approach of using torch light and further instrumentalised it to reflect on the project’s theme. Soon, I understood that it was not about picking a style and applying it to a place. Now I tend to go with the flow and try not to bring the baggage of my previous works to the new ones.

From the series Change of Course (2012-2018).

SM: I am interested in how music is a central component that flows through your projects. In Change of Course or Red is the Colour of the Spring, you have recorded musical performances and incorporated them into the works. How do you conceive of your relationship with music vis-à-vis photography?

PS: I have not really thought about how music influences my visual language, but music has been around me for a long time now. The people I have grown up with for almost the last two decades—the friends I have had since high school—have all been musicians.

Earlier, I would travel with musician friends, carrying their guitars or drums and setting up their stage. I used to make a lot of music videos through Fuzz Factory Productions, and that is how I first became involved with music. Also, in my personal work, wherever I find music, I always record it and try to incorporate it because it has always been around me. I know how powerful music is and how it can influence people because it has influenced me. Even though I am not a musician, I try to incorporate that into my work wherever possible, even if it is not directly related to music.

From the series Change of Course (2012-2018).

The Asia Arts Game Changer Awards are an Asia Society India Centre initiative. To learn more about the 2022 edition of the Asia Arts Game Changer Awards India, revisit the ASAP | art podcast in which Najrin Islam speaks to Inakshi Sobti, Chief Executive Officer of the Asia Society, India about the event. Also read interviews with the winners of the 2022 edition, which included Himmat Shah, Jasmine Nilani Joseph and Sumakshi Singh.

All images courtesy of Prasiit Sthapit.