Of Landless Belonging: Amid the Villus by Sumathy Sivamohan

The renowned Sri Lankan artist, poet, performer, filmmaker and academic Sumathy Sivamohan’s latest work, Amid the Villus (2022), is her first documentary project. It offers a poignant exploration of lives intersected by land, conflict, displacement and memory. The film was recently screened at Parda Faash, a festival of South Asian films organised by the Asia Society India Centre on 27 and 28 April 2024.

The villagers of Palaikuli.

Set in post-civil war Northern Sri Lanka, Amid the Villus tells the story of Palaikuli, one of the four villages in the dry scrubland of Musali that was affected during the three-decade-long civil war that started in the 1990s. The film opens with still, long shots focused on the savanna grasslands, bushes and stone heads that dot the landscape of Palaikuli. Sivamohan makes it evident that this is as much a story of a land that has been inhabited, abandoned and reclaimed over the course of the last couple of decades, as it is the story of its people, first displaced and then returning as refugees. In this manner, the film highlights how their identities, struggle and existence are defined by the geography of the place they come from. The documentary brings forth multiple perspectives and narratives, giving space and due attention to the voices of Palaikuli. The villagers recount their history through their association with the land that was once their home and has now been taken over by the state.

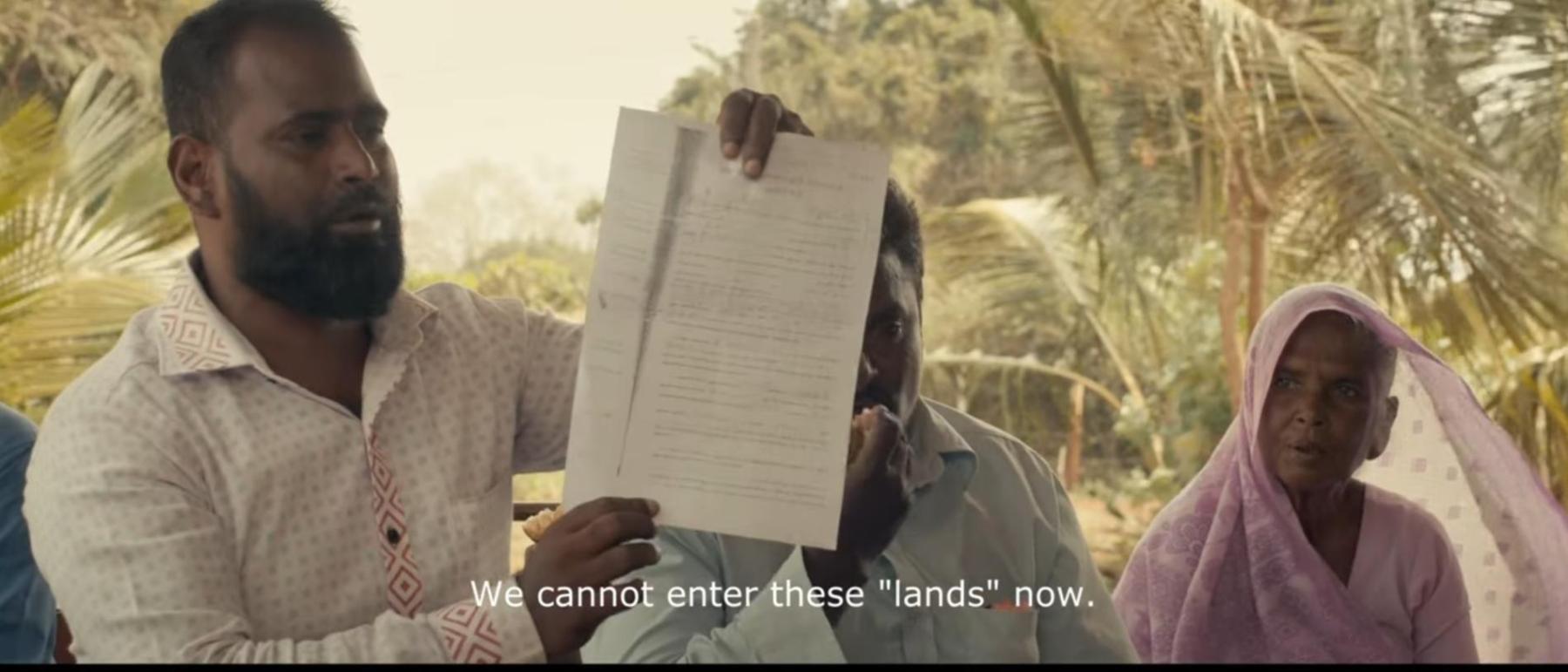

One of the men pointing out how the Gazette notification now bars them from entering lands that they once called their own.

As one of the documentary subjects deftly points out: "When they gazetted the land in 2012 and 2017, they did not come here to do so. They did it via satellite." Sivamohan goes behind and beyond the arbitrary lines drawn to declare certain areas as forest reserves under government issued gazettes in order to highlight the aftermath of such decisions on the lives of already marginalised people.

Reminiscing the corners of the village that they once called their own.

There is a subdued thehrav, or pause, with which the filmmaker charts her journey to unfold the many layers of complexity shared by the people of Palaikuli. These are revealed through questions of home, belonging, intergenerational attachment to land and its identity as well as survival and livelihood. Such queries direct and locate the conversations within the context of loss and displacement, owing to the country’s sociopolitical climate. Whose land is it? Does inhabiting lead to ownership? Who has the authority to decide what belonging is?

Sivamohan engaged in an impromptu conversation with the villagers at a local tea-stall.

According to the Sivamohan, it was a conscious choice not to include any parallel rhetoric of environmental activism and land protection that largely dictated the Sri Lankan government’s reasoning behind declaring the area as forest land, thereby forcing displacement. She added that the environmental lobbyists and policymakers already had the space to vocalise their perspective—their side of the story was out there in public, loud and clear for anyone to follow. Amid the Villus rather engages with the often overlooked aspect of conservation practice—the underlying complexity of the relationship between nature and its dwellers.

A Palaikuli woman looking back on the land she grew up on with her family and two sisters before getting displaced.

The people of Palaikuli were forced to abandon their homes, lands and livelihoods during the decades-long civil war. In its aftermath, as they returned to the place they had once fled, they found themselves landless, homeless and with no choice but to start from scratch. The stark difference between how the state and the people view and understand land comes out in an interesting juxtaposition. A scene in which a resident draws out the land of Musali, carving out the forest, reservoir and nearby villages that Palaikuli is surrounded by, is followed by a scene in which the camera zooms into the official government notice in the gazette. For the former, it is the place that they have breathed life into for generations, while for the latter, it is a piece of territory now under supervision. Inspired by the works of the late Professor S.H. Hasbullah, Sivamohan’s attempt to document the untold stories of the country’s internal displacement is at its best grounded in the geopolitical reality of the region as well as resonant of the universal questions of belonging and the collaterals of war in its aftermath.

Sumathy Sivamohan in a discussion with the Palaikuli villagers.

Amid the Villus gives shape, face, name and voice to a demographic that is often relegated to the footnotes of the larger conversations around conflict and conservation. In doing so, it puts their stories at the centre of the debate and acts as a fulcrum to direct our approach to understanding and unfurling its complexity. Even when the filmmaker was wary about broaching the controversial topic, the people of Palaikuli were not hesitant to tell their stories without fear. With a runtime of 47 minutes, the film offers a peek into the lives of people who were uprooted and are still struggling to find a foothold in the land that they once called their own.

To learn more about some of the films screened at Parda Faash and other festivals, read Banhi Sarkar’s essay on This Stained Dawn (2021) by Anam Abbas, Sujaan Mukherjee’s essay on Taangh (2021) by Bani Singh and Shranup Tandukar’s essay on Before You Were My Mother (2022) by Prasuna Dongol. Also, visit Pramodha Weerasekera’s curated album from Cassie Muchado’s photo series After Life (2011–16), Annalisa Mansukhani’s conversation with Jasmine Nilani Joseph and Ankan Kazi’s conversation with Sinthujan Varatharajah.

All images are stills from Amid the Villus (2022) by Sumathy Sivamohan, courtesy of the artist and Asia Society India.