The Journey of a Printmaker: In Conversation with Anupam Sud

Anupam Sud, whose career spans several momentous decades, was recently honoured with the Asia Arts Vanguard Award by the Asia Society India Centre at the India Art Fair 2025. Her work is a fixture in any history of Indian modern art today, and while a range of impulses have informed the trajectories of her illustrious practice, it may be argued that her enduring relationship with printmaking has yielded a pioneering expressive potential for the medium. In this conversation, Sud reflects on the various conditions—socio-economic, cultural and infrastructural—that shaped her journey as a printmaker and an artist.

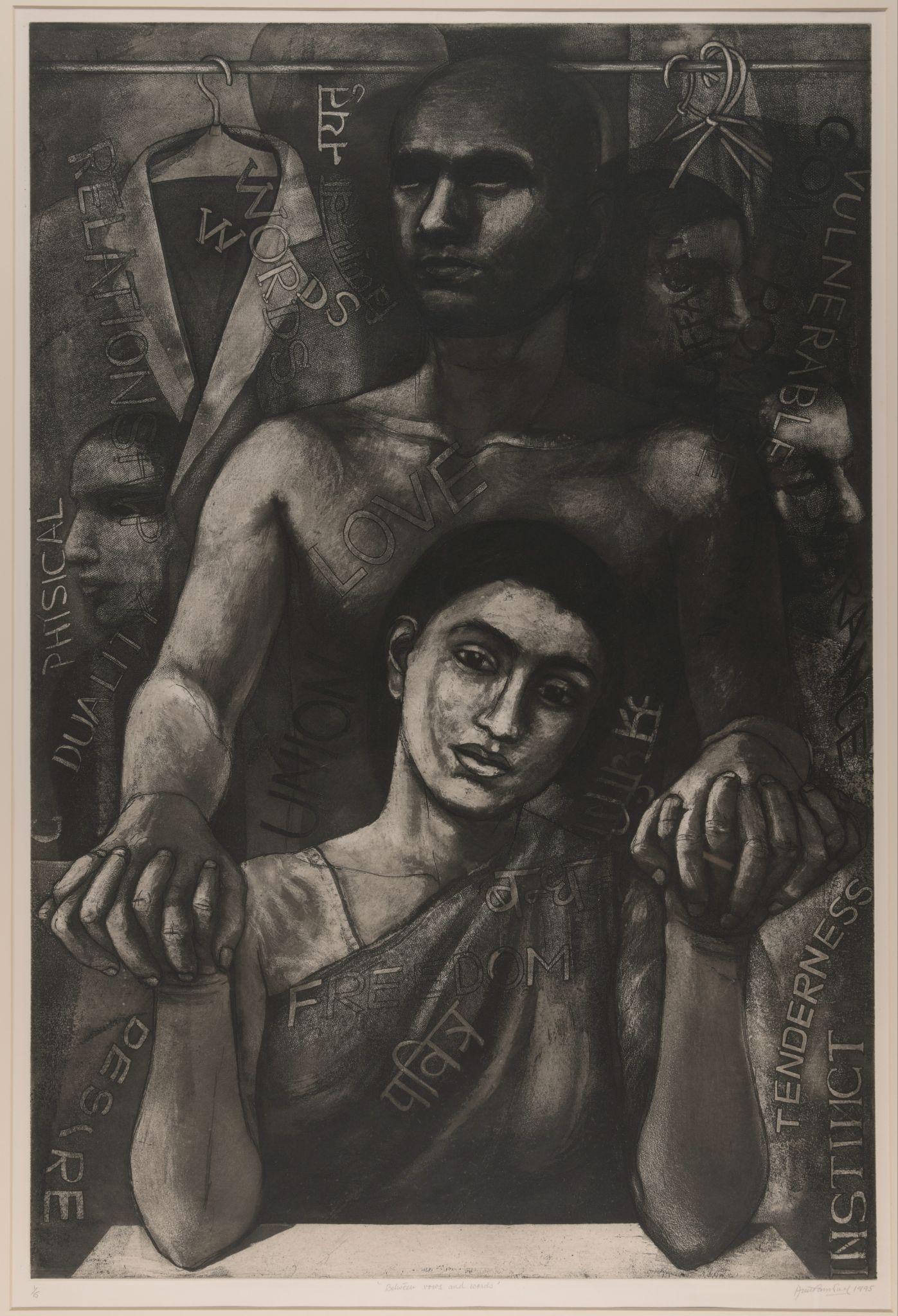

“Between Vows and Words.” (1995. Etching, 94 x 63 centimetres.)

Adreeta Chakraborty (AC): Your life’s work as an artist, but particularly as a printmaker, has been celebrated widely over the past decades. How did you get into printmaking?

Anupam Sud (AS): Back when I was starting out, they would only issue diplomas in three things: painting, advertising (what they would call applied art) and sculpture. These were the only options. Besides these, there were subsidiary subjects that we would be taught but there was no question of choosing and specialising in any of them. I took admission in painting and one of the subjects as part of that course was printmaking. Younger students would be offered that subject, and we would be taken through linocut and woodcut primarily. When you came to the senior classes, you could do either murals or print making for a year and we were enrolled in the diploma programme for five years. Otherwise we would have one class for mural, one class for woodcut and linocut—everyone had to go through that. So, if people have to make a choice about what they want to do, they first have to experience everything. They have to experience how they relate to the medium.

I used to look at printmaking, the ones who would do it: haath kaale, mooh kaale, kapde kaale (hands stained, faces stained, clothes stained). And I used to feel this is one subject I am not going to touch: just let the class end and I will wash my hands off this forever. I did not know then that printmaking would take such a hold of me and never leave me again.

My teacher Jagmohan Chopra was kind of an inspiration for all students. And I have been a teacher, so I realised that you begin to see a student’s possibilities early on—you understand what directions they could go and with what medium.

The point at which difficulty ends, a certain thing becomes a challenge, and some people like to enjoy that challenge. Whatever comes to you easily, you stop with that after a while because it does not really still hold you there. Whatever is very challenging, you are drawn to that. Printmaking was very challenging, because in our time, it was not at all developed. It would mostly be limited to line drawing and adding a little bit of aquatint. Nothing beyond that. When we were in our final year, the India-China war had just broken out, in the 1960s. And as a result of that, zinc, copper and all the things that we used for etchings went underground. They were used to make instruments, weapons, etc. So if you had to do printmaking, and to get zinc plates in particular, you had to go to ten shops to find wherever the zinc was available. So you would also need more money for that, and the quality one was looking for was difficult to get. Jagmohan Chopra was very enterprising, so he figured if metal was not available, we could use something else like cardboard. We would create surfaces which can be printed like in intaglio. You know the Indian currency is printed in intaglio. Take any fresh note and see—you will feel the lines are a little raised. So we would use cardboard, and in college, we would get these boards for mounting. There was a company called Choksi in Mumbai which made these good quality, dense mount boards. So we started printing on these in intaglio, etching on these.

If you wanted ten different colours on the plate, you had to cut the plate into ten parts. I would split my plate into ten according to the colours, and each piece would be coloured separately. Then together the print would be taken. It was something we were just doing; it was very new. We were finding our own ways and it was quite titillating to see the results. There was that sense of wonder, like in childhood. On the basis of these prints, I applied for the British Council scholarship because I had made a huge number of them by then. What I had never wanted to do ended up taking such a hold of me and I love taking on challenges—that is my temperament.

For instance, when I was teaching, I saw a kid who had a discipline problem and the authorities wanted to expel her. I took her into my class. They said you will die trying to handle this one and I said, “Let’s see.” Today, the toppers in that class are unable to continue with their practice but that girl is continuing.

Anyway, when I went to London, I saw different kinds of printmaking happening. Traditional Britishers like black and white. If you go to France, they love colour. I was already working in colour, so while I was in London I worked in black and white, their system of intaglio. I learnt that diligently, but I also made detailed and copious notes for when I come back to India, so that our own equipment and pedagogies should not remain any less than those of any European country.

We did not have that intaglio tradition so much in India. Here, there used to be more wood prints, like on fabric. For instance, the images in the Guru Granth Sahib are also made out of woodblocks. There was not a clear tradition in India but there was a setup which one could use in different ways, although printmaking was not developed as a medium like that. I was determined that we—here in India—should not be any less. I made notes about the equipment and chemicals being used there and tried to find equivalents for the same here. I was constantly in touch with Mr Jagmohan Chopra, my teacher. And we grew closer through that period while he was still teaching at the College of Art. Back then you could not take photos, of course, so I would make drawings and document what I saw, with dimensions of the equipment. My instructor there—he was Portuguese—would ask me what I was doing and I would say that I was documenting these to create better systems back in India.

So before I returned, Mr Chopra had gotten almost everything ready, including all the equipment and chemicals. I came back and started teaching at a school at that time. After work, I would go to the College of Art and see what all he had done. We even designed a machine for printmaking and formed a collective called Group 8 for people who were interested in continuing. My concern was that this was a subject for which there was very little possibility to continue with after college. With painting, if you do not have an easel, you could just put your canvas on a chair and paint. But for printmaking, you would need stools; to flip the print, you would need space; and you would need to keep the acid away from the furniture, from the work and from the people. Printmaking is not a single person’s medium—you need a group for it!

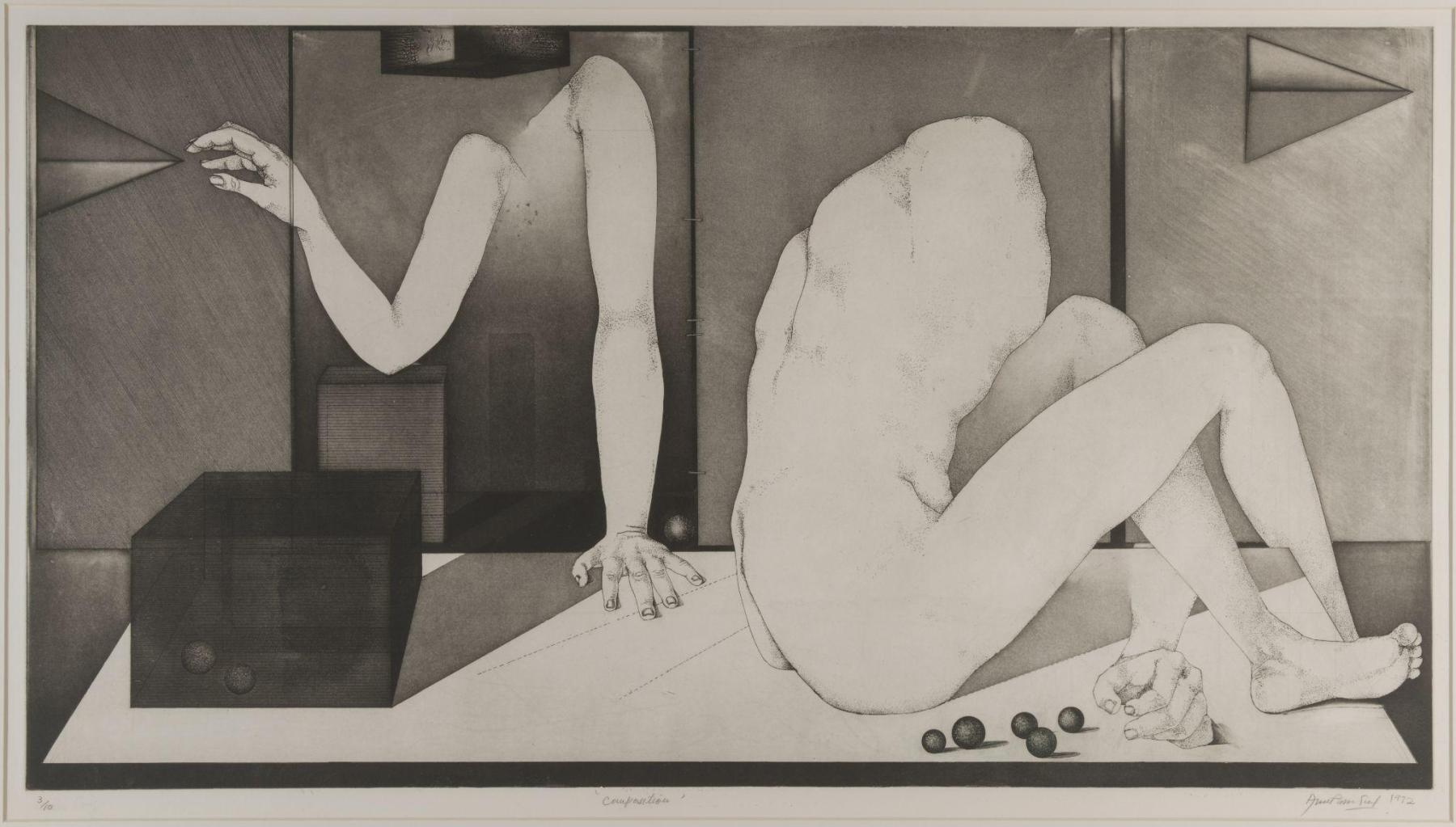

“Composition.” (1972. Etching, 49 x 90 centimetres.)

When I came back, I was teaching in a higher secondary school. After work, I would come to the Group 8 studio Mr. Chopra had set up and work there. I would bring my food from home, eat there and then go back home. Printmaking as a medium had not had much growth at that time, so we were playing around with a bunch of new things. When you are working with a material for a long time, the material starts displaying its ability and its possibilities, right? And you want to control that; you do not want the effects to be accidental; you want controlled results. So we were engaged in that and Krishna Reddy came and lauded our efforts, our experimentation. They had rationalised and systematised a bunch of the techniques we were trying out, while we were thinking hum bohot badi koi beimaani kar rahe hai (we are committing some great wrongdoing) as we figured out these tricks. We did not think it was any achievement.

“The Rear Window.” (1992. Etching, 49 x 78 centimetres.)

Eventually, printmakers started forming guilds and groups in every city. The government started giving more grants for buying various machines. The whole movement started. And it kept on growing and growing. There was no dedicated purpose for it. People kept on doing it and it kept on happening. And if there are twenty people working together, there will be twenty ideas too! Everybody’s idea is taken care of.

Group 8 put in a lot of effort into promoting printmaking. Soon, the Fine Arts Department at MSU Baroda joined us, Santiniketan joined us, and we started having printmaking exhibitions. We asked for prints from all over India and then travelled with those works to different places. Baroda supported us, another college in Patna and another in Chandigarh (I had moved there as principal of that college) also supported us. Once a plant starts growing, it keeps on growing. All this started happening in the 1970s, but by the time I was out of college in ‘67, already the tree was growing.

Gulammohammed Sheikh of Baroda contributed; everyone did—and not just monetarily; people really invested in having the medium grow to its potential. There were creative and intellectual exchanges everywhere, new ideas all the time. We would have conferences routinely.

AC: When you are experimenting and you want to control your material, there are also going to be these discoveries that come through by accident, and once you have those, do you try to discipline them?

AS: Yes, and if you study the unpredictability and chance discoveries of that process consciously and manage to write a book about it, that is an achievement worth praising.

AC: You have worked with lithography, screen printing and intaglio, but most often with zinc plates. Is there a reason you were drawn to zinc or did it just happen by chance?

AS: That is the traditional way, using a metal plate, but a copper plate costs a bomb. With my job, there was also only so much time I had to gather resources and all of that material. Zinc is reliable; one can use aluminium also, but it is very unpredictable and begins to give way very fast. The lines you would get on a copper plate, zinc cannot match those, and the lines you would get on zinc, aluminium would not be able to match. With zinc, the material costs less and the work too is durable.

AC: A well-noted focus of your work is on the human body. How has printmaking related particularly to that subject?

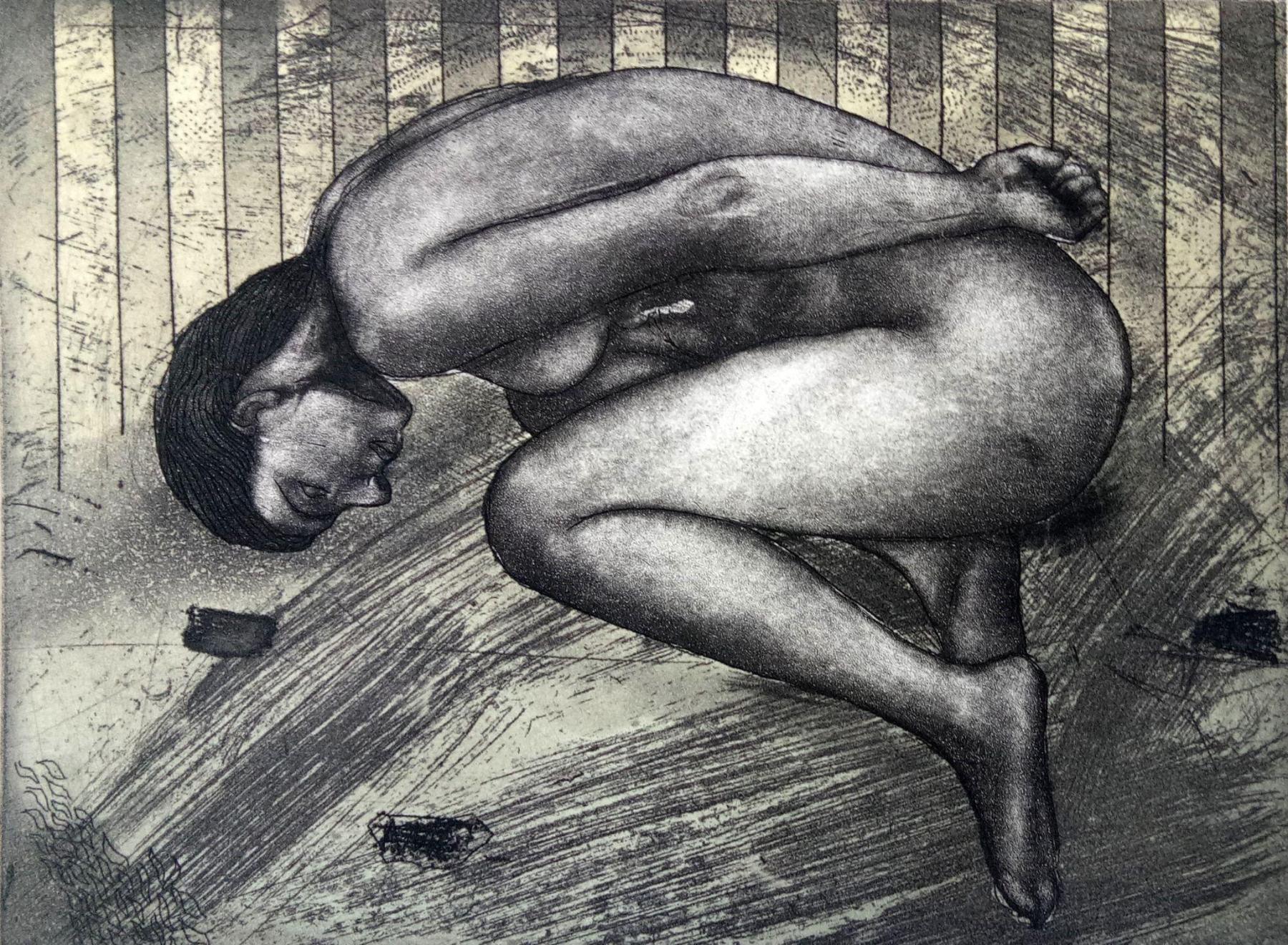

AS: My sensibility is such that I love seeing light falling on the body. The chiaroscuro, the dimensions added by the light—if I am able to render that in my drawing, if I am able to achieve that effect, it gives me complete satisfaction. Achieving that is the main thing.

I suppose I could have explored the body through painting as well. To continue printmaking was more difficult than to continue painting, and hence I was drawn to the former. And then there is one other advantage: they say printmaking is the most democratic medium—because you make more prints, right? It is not just one person that the work goes to; it can go to as many people as there are editions being made. Though it takes time and you are spending so much energy, it all becomes worthwhile. They call it democratic because average people can also afford to buy prints.

AC: In your works, the bodies are often placed within larger architectural contexts. There is a huge structure and then there is a body within it—sometimes constricted, sometimes juxtaposed. What is your relationship to theatricality when you think of staging a subject in your print?

AS: I think people should see my work and make that decision on their own; no artist should retain control of that because the gaze has now moved outwards. Whatever you are making, unless you are making it for yourself, it has got to have something that speaks to other people, that will have somebody or the other interested in it. So you create a situation where you are expecting the participation of the viewer, and it may be that they get just the opposite idea from what I have done. I have no objection to that. Just making work for myself is not enough, I respect the viewer to take hold of the scene and identify the stage. I have strewn a web of paths through my work and now you have to make your way through them the way you see fit, the way your own experiences drive you. If you can invite other people into your work, or make something that will speak to others’ experiences, they catch on to your sensibility, but it is now coloured and made richer by their own associations. Once they look at your work, they begin to word their own experiences and sometimes the meanings they arrive at surpass the work—I like that possibility, that is how the art survives and takes on a life of its own.

I do not want to give answers always because I want to protect my characters, protect their vulnerability as subjects and as bodies. Women all the time have that vulnerability and maybe that reflects in the way I stage them in my works, based on my own experiences as opposed to the greater freedom and mobility men enjoy.

“Nestling.” (2015. Etching, 14.3 x 17 centimetres.)

The Asia Arts Game Changer Awards are an Asia Society India Centre initiative. To learn more about the awards, revisit the ASAP | art podcast in which Najrin Islam speaks to Inakshi Sobti, Chief Executive Officer of the Asia Society, India about the event. Also read Santasil Mallik's two part interview with Prasiit Sthapit, who won the Asia Arts Future Award (South Asia) in 2024 as well as interviews with the winners of the 2022 edition which includes Himmat Shah, Jasmine Nilani Joseph and Sumakshi Singh.

All works by and courtesy of Anupam Sud.