"Cloth Protects Us": In Conversation with Jayeeta Chatterjee

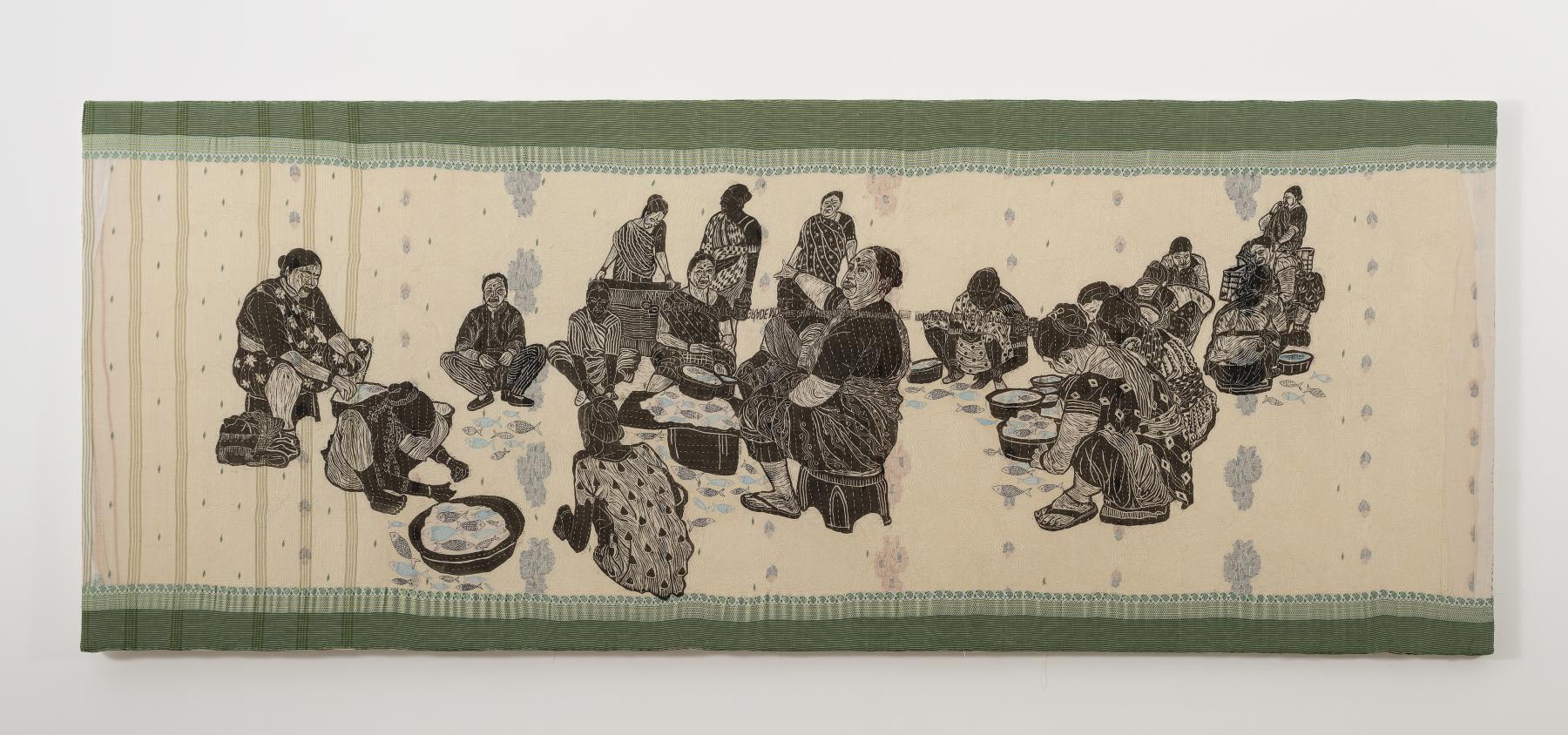

Over the years, printmaker Jayeeta Chatterjee’s practice has shifted from an interest in architecture towards “those who turn that architecture into a home,” with attention to the complex dynamics that underlie the dailiness of the domestic. Her work now focuses on questions of women’s labour, leisure, social rituals and aspects of the familial that are concentric to the social, such as migration (in “Cycle of Life (I)”), and violence against women (in “Portrait of Lakshmi”). Chatterjee’s practice involves woodcut printmaking, often overlaid with Kantha embroidery, on used saris that she collects from women she has interviewed during her travels; time at artist residencies, such as Chemould CoLab in 2023; and her days at home in Bengaluru. Each stitch is administered painstakingly atop prints of women working and resting together, both within the domestic space and outside it. In Chatterjee’s work, the ethos of the domestic—such as acts of care-giving, deliberating and gathering community—spills into the outdoor spaces women occupy, such as the marketplace and neighbourhood. The series Jibon Ghore o Baire 3 (Life at Home and Outside, 2024), for example, is alive with selling and purchasing, discussion, intimacy, advice-giving, child-care and rest—all happening simultaneously in shared spaces.

This year, Chatterjee was the recipient of the Asia Arts Future (India) Award, at the Asia Arts Game Changer Awards organised by the Asia Society India Centre. In this interview, Chatterjee reflects on the impulses that drive her process of documenting and narrating women’s work and leisure, and the questions that are shaping her ongoing practice.

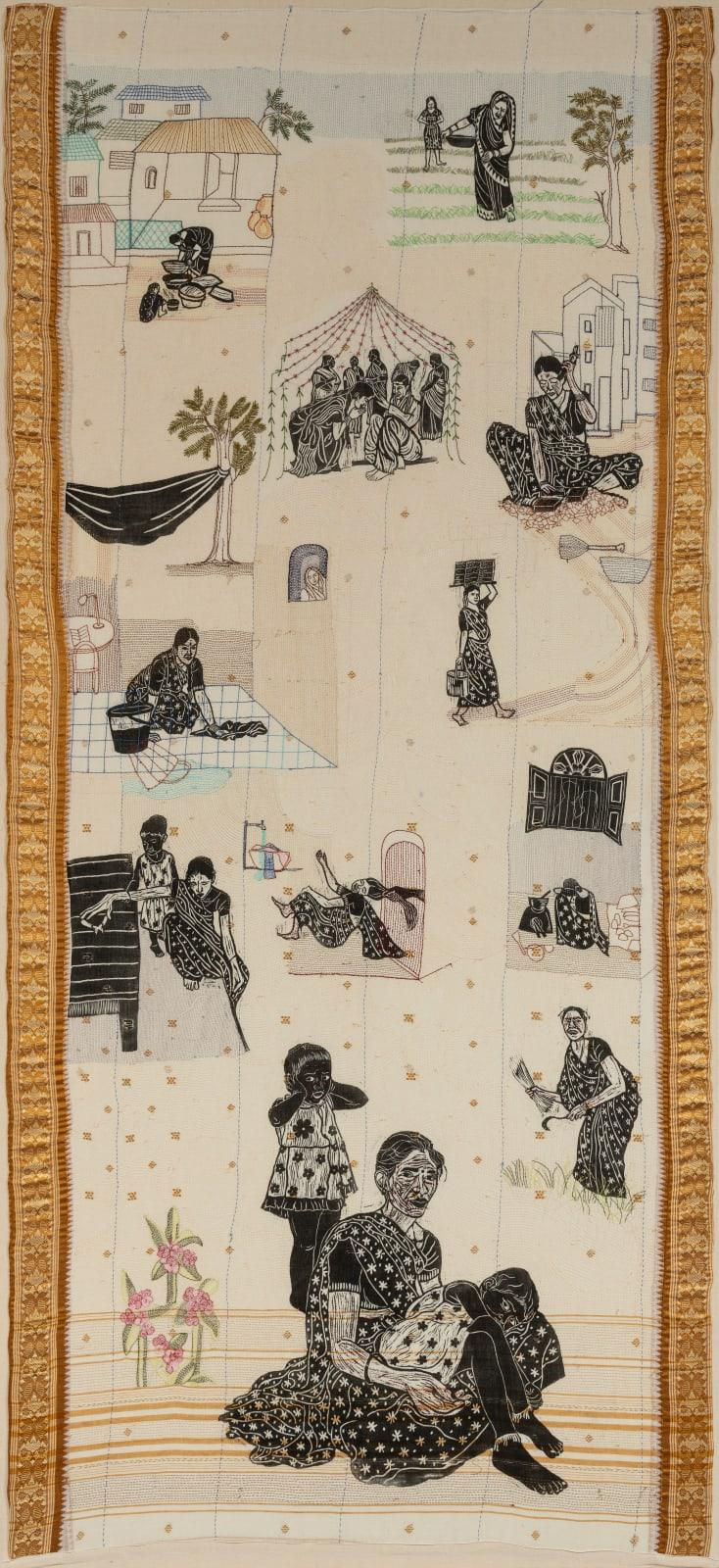

"Portrait of Lakshmi" (after Nilima Sheikh). (Jayeeta Chatterjee. 2023, Woodcut print and Nakshi Kantha embroidery on cotton saris, 248.9 x 110.5 centimetres.)

Aparna Chivukula (AC): Your work narrates the stories shared by women you have met while working and travelling. How did you arrive at your present process of documenting and recording conversations with others about their experiences, both in the domestic space and outside it?

Jayeeta Chatterjee (JC): There was definitely a learning curve. It can be very difficult to speak to strangers sometimes, because I do not know how they will react to me. At times, I do not know the regional language, such as in Hyderabad, during my Banyan Hearts residency. It was very difficult to speak with Lakshmi (whose story appears in “Portrait of Lakshmi” [2023]). I do not understand or speak Telugu. I had an artist-friend help me by translating. I would talk to him in Hindi and English, and he would translate it into Telugu for Lakshmi. That is how we recorded our whole interview. In Mumbai also, during my Chemould CoLab residency, one of my friends helped me communicate in Marathi with the Koli women at Sassoon Docks. Though they spoke Hindi, they were more comfortable in Marathi. Having someone local help makes the process much easier and makes others trust you more easily too. If you know a region’s language, its people feel safer and more comfortable to speak with you. When I ask someone for a conversation, they could say they are not interested, or say, “Who are you? I do not want to talk”—that happens too. And other times people are very welcoming and share everything about their life. I am now prepared mentally for both responses. It is their private life, people can choose to say no, and I respect that. Before, I used to nag them, ask them why they were not speaking to me and request them to say even a little, but now I know not to do that. I can imagine I would get irritated if someone did that to me. In all this, I have been learning how to talk to others and how to make them feel comfortable enough to talk with me. I share with them the work that I have done till now—the images and stories from my practice—and then, often, they too become interested. They ask how I made certain parts of my work and share with me what they like about it.

If I have the time, I like to observe for two or three days. In Mumbai, I went to the Sassoon Docks often, visited the market in the early mornings, and as I became comfortable, a few people there began to recognise me as well. Then it was easier to communicate with them, about where I am from and the work I do, and requested to speak with them. I asked them how they manage their households and their stories around that. Then, if they were interested, we would talk, and I would take pictures of them with my phone.

In my practice, I feel the need to communicate with someone—it is a narration-based practice, based on real stories and real human beings. My work is direct, using what I observe and what someone narrates to me. Every artist finds out what is a necessity in their process, what kind of research they need to do. For some, it could be reading poetry or daily sketching—each one finds their own way.

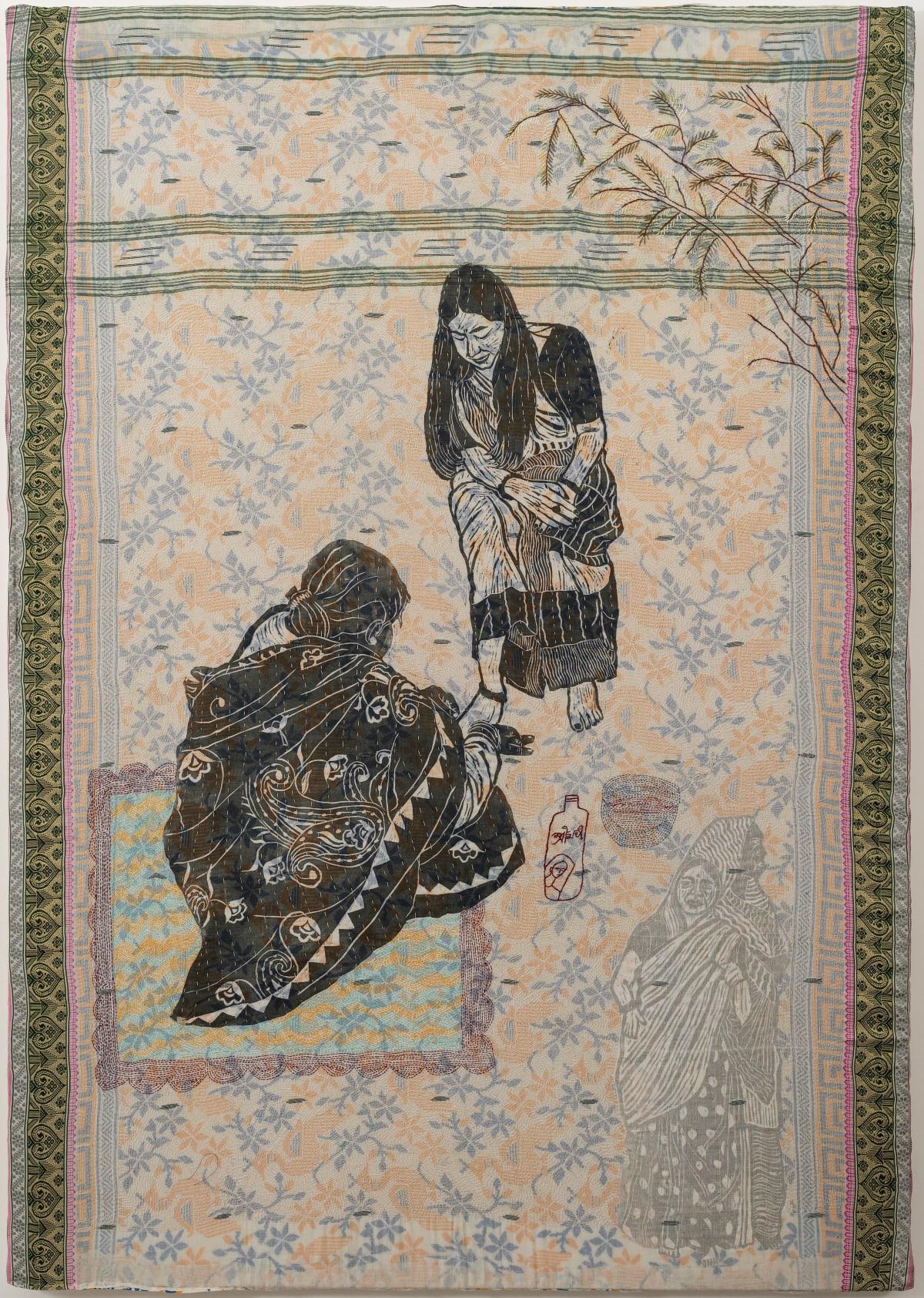

"Alta - a sign of love" (Jayeeta Chatterjee. 2023, Woodcut print on recycled cotton sari, Nakshi Kantha and applique [three layers], 147.3 x 103.5 x 3.2 centimetres [stretched].)

AC: How do you think of the small motifs in your narrative work, both those carved into your woodcut compositions and those woven into the saris you print on?

JC: The motifs are deeply connected to the people whose story the piece narrates, that is why I use them. I do not really think of them as ‘decorating’ the work. My work “Portrait of Lakshmi”—made in response to Nilima Sheikh’s series When Champa Grows Up—is full of flowers, because when I met Lakshmi during a residency, we would chat behind a flowering tree in a garden that she used to water every day. She had a connection with the garden space, she used to care for its flowers and plants. For the three months that I was at the residency, we used to speak in the afternoons in the garden. Her telling of her story had that connection with that tree. In the work, I portray her childhood, her marriage, her village in Andhra with its mud houses and her parents farming—everything is related.

"A Summer Afternoon" (Jayeeta Chatterjee, 2023. Woodcut print and Nakshi Kantha stitch on saris [two layers], 182.9 x 221 centimetres, [single sided, suspended].)

“A Summer Afternoon” (2023) is a work which is very personal to me, because it depicts my mother, my grandmother and my grandmother’s sister. We were all enjoying a summer afternoon with kulfi (ice cream). We were lying on a floral bedsheet—a blue bedsheet with yellow flowers. I kept those original motifs and original colours in the work, because the choice of bedsheet and colours belonged to my grandmother. They are representative of her taste, so I did not want to change that.

The motif also works as a metaphor. In Art Basel, last year, I showed “When a Child Itself is a Mother,” in which I use bushes, unbloomed flowers and buds to tell a story about child marriage. A child who became a mother when she was only seventeen years old. Her financial condition forced her to get married. And after that, she immediately became pregnant despite being a child herself. Here, the motif of the unblossomed flower or the bud is symbolic.

AC: What draws you to the gesture of working over your prints with a needle and thread, the layering of the Kantha stitch over the woodcut print on cloth?

JC: The layering in the work is to do with the stories I am telling—they are full of emotions and personalities, and I want this to come through in the cloth, through the technique of quilting. Sometimes I use multiple layers of cloth, and sometimes only one, stitching another layer as the background. The technique I use, Nakshi Kantha, is a quilting technique from Bengal. It is an important traditional technique. Unfortunately very few people know about it, or how to do it, and so I want to archive this traditional technique through my work.

"Absence is missed" (Jayeeta Chatterjee, 2023. Woodcut print on recycled cotton sari, Nakshi Kantha [two layers], 106.7 x 106.7 x 3.2 centimetres [stretched].)

AC: You mentioned that the used saris which you print on require delicate handling as they can rip easily. In this way, your practice also involves administering care to the work, materially, along with the attentiveness required to compose a borrowed narrative. The gesture of going over the print with a stitch may even appear to be a kind of protection—the Kantha stitch lends both a kind of softness as well as a kind of sturdiness to the quilt. Can you share more about the practices of caregiving and attentiveness in your process?

JC: I have not thought of it like that before, but it is true. The stitching protects the sari too. I have to be very careful while stitching. The saris are very soft and even the slightest excess pressure could lead them to tear. The technique used to make this work and its subject matter are deeply related. The saris I use are collected from the women I have spoken to, they gave me their old saris, ones they wore through their days, including during their work and their leisure time. So these saris have had their own journeys, histories and emotions. The sari cloth is a very intimate material with which to narrate these stories, it has so much connection with those who have worn it. Cloth protects us, it is the extended skin of our bodies.

I struggle sometimes with how to narrate particular stories. It might seem like only a one-line or two-line story, but it is actually someone’s life, and they are leading that life every day. So, to do justice to their story is really important to me. That is my biggest worry—how to do justice to someone’s story, the part of their life they shared with me, even if it is one moment. And to tell that moment in the correct way comes with a lot of pressure. It is a big responsibility.

AC: Your solo show at Chemould Prescott Road last year, An Eye Inside, displayed both personal, familial narratives as well stories you came across during your travels, with a focus on the daily, domestic lives of women. Are there aspects of the domestic that you find have been obfuscated by romanticisation and stereotyping? What are the complexities and conflicts within the domestic space that you would like your work to take on in the future?

JC: For the last two years, I have been collecting documents on child marriage. It is very difficult to obtain. Convincing NGOs to speak to me is almost impossible, because at the end of the day, I am making art and they may not take that seriously. It is not that I want to go to organisations and interview them. I have sent out proposals to conduct workshops and work with organisations. My job is not to interview people. When people ask me how I see my own work as an artist, I tell them: “I am not a reporter. I am an artist, and when I speak to people, I do not talk as an artist or as a reporter—I am trying to build a connection with them as a woman, as a homemaker myself.” It is because of this that people have trusted me and shared things with me.

Thinking about stereotypes—I have not shown the aggression, anger, depression and anxiety of the domestic space in my work until now, but this is definitely something that is part of the story—mine and those of other women. There are all kinds of frustrations, whether with family, physical health or even mood swings. In my future work, I would like to express these emotions too.

To learn more about the recipients of this year’s awards, read Adreeta Charaborty’s conversation with Anupam Sud and Pramodha Weerasekera’s reflections on Shilpa Gupta's practice. To learn more about previous recipients, read Santasil Mallik's two part interview with Prasiit Sthapit, who won the Asia Arts Future Award (South Asia) in 2024 as well as interviews with the winners of the 2022 edition which includes Himmat Shah, Jasmine Nilani Joseph and Sumakshi Singh. Also revisit the ASAP | art podcast in which Najrin Islam speaks to Inakshi Sobti, Chief Executive Officer of the Asia Society, India.