On Violence, Dispossession and Arts Pedagogy: In Conversation with Karachi LaJamia

The arts collective from Pakistan, Karachi LaJamia, recently received the Asia Arts Future Award (South Asia). The award celebrates promising contemporary visual arts practitioners from South Asia who display a commitment to their craft and are building a body of work that enables a deeper understanding of their regions and cultural landscapes for South Asian audiences and beyond. Currently based in Canada and the Netherlands respectively, Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani founded Karachi LaJamia in 2015 as a nomadic, collective arts space seeking to politicise art education and explore new radical arts pedagogies and practices. The duo engage with artists, students, researchers and activists to occupy public spaces in Karachi as sites of study, thus disrupting imperial modes of knowledge production and circulation. The collective seeks to build solidarity with ongoing struggles of resistance in the city’s historical neighbourhoods and along its coastline against developmental regimes that dispossess and displace Sindhi and Baloch indigenous communities to whom the land belongs. In this two-part conversation, they share their early frustrations with the failure of university arts education due to its compliance with architectures of militarisation, leading to decaying infrastructures and disappearing ecologies—which led them to found Karachi LaJamia. They also deliberate on their journey toward the playful and experimental exploration of a political pedagogical practice that witnesses and documents devastating transformations in Karachi’s landscape while bringing into conversation activists struggling on the ground with the larger arts community.

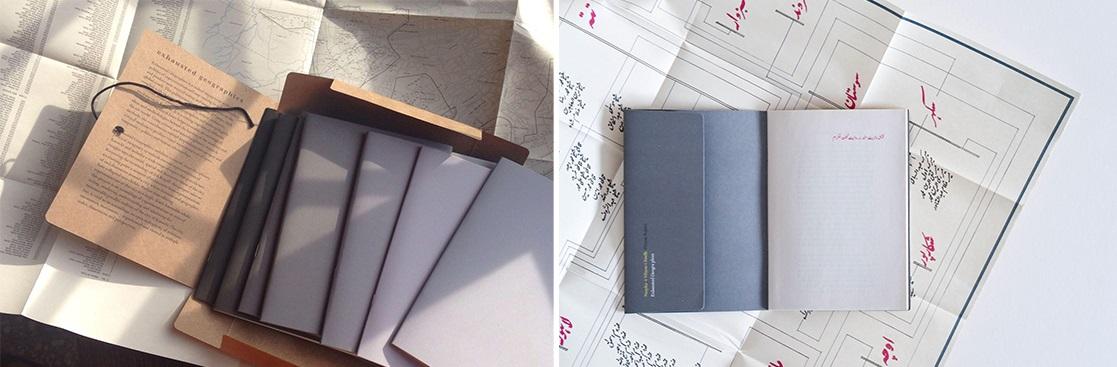

Exhausted Geographies Vol. I (2015), a collaborative publishing project by Shahana Rajani, Zahra Malkani and Abeera Kamran.

Radhika Saraf (RS): Can you please tell us a little about the beginnings? You describe yourselves as “anti-institution,” what made you feel the need to start Karachi LaJamia in 2015?

Zahra Malkani (ZM): While we have moved away from the anti-institution framing, we started Karachi LaJamia in response to shifts in the general atmosphere and climate in the institutions that we were working in. This was with regard to surveillance, what could be taught and how much we could play and experiment within the classrooms of universities. When we had just started out, it felt like a very permissive place. And as we saw a shift within the university, there was also a shift happening in the general atmosphere—of compliance. Of course, that shift was not overnight or unprecedented, but rather a new stage in a longer process of cracking down on cultural institutions, activism etc. Responding to that moment, we were really interested in expanding the possibilities of pedagogy and learning together, specifically in the larger context of the city. Karachi is a city that at the time was being understood and represented as this really dangerous, crime-ridden and terrorism-ridden city, which was not our experience of it. We wanted to see what was possible when we put our different communities in conversation with each other—our communities in activist spaces with our communities in academic and arts circles.

At the same time, our shared concern about the shrinking space for thought and experimentation in the university led to us becoming really interested in documenting, studying and researching that shift while it was happening. So while we were conducting these experimental courses in public spaces in collaboration with different activist organisations in Karachi, we were also researching and investigating the ways in which the institutional spaces and universities across Pakistan are being not only surveilled and censored but also mobilised and co-opted for militaristic aspirations by the Pakistani state. But one of the reasons we moved away from the “anti-institution” framing a little bit—not that it is wrong—is that we both share a deep investment in the present and future of institutions in Pakistan and the hopes and dreams of what that can do for students, artists, academics and people in Pakistan.

Shahana Rajani (SR): Really early on, as Zahra and I were beginning to work together, we watched with increasing alarm as the city was being militarised and as activists and cultural workers were being targeted and killed by the state. We also noticed that out in public spaces, there was a real absence of artists and students from our art schools or universities. Our larger art community was missing from protests at a time when the cultural world was under attack. That experience made us realise that a big part of that absence was a result of the way in which art is being taught and the way in which students in art schools are being encouraged to keep their practice and life separate from society and politics. There is a much longer colonial tradition of depoliticisation of education that has been in place for decades. And that is one of the reasons that we specifically wanted to do a project at the heart of which was pedagogy and radical pedagogy—the belief that education is really at the heart of our lives and the future.

Radical Karachi Tour, a session from Karachi LaJamia’s first course, Art & Politics in the City, 2015.

RS: Your initial statement around the murders of Sabeen Mahmud and Dr Waheed-ur-Rehman was very strong and very sardonic—you speak of the military state and the liberals who were at one time part of the anti-Zia struggle but have now been co-opted. What, to you then, was the failure of the liberal system of knowledge production that prompted your project The Militarised University?

SR: We found ourselves in a moment where we were emerging artists—young and teaching in art schools for the first time. We had both just returned from our graduate studies, and we noticed that there was a really rich cultural tradition of protest and resistance from the Zia dictatorship era that was often remembered and invoked in these spaces. But the legacy of that struggle, of a spirit of dissent and collectivity, really seemed to be missing from the art schools and art worlds we were moving around in. This made us really frustrated. I mean, that statement, the tone in that writing—we recently re-read it and I could really remember how angry we were at the situation and at what we felt were the failures of our community. In that moment, it was also about the romanticisation of past resistance, but then, in the present, feeling the silence and sterility of those very same spaces and institutions. The statement ended up becoming the start of Karachi LaJamia. Now, over a decade later, our perspective has shifted on this. At that moment, we were frustrated by a lack of politicisation. However, it was not necessarily that there was a lack or complete absence; it was just that we were not part of those circles and those spaces. And so much of the work we have been doing together since is finding those networks, understanding that legacy and engaging with histories of those kinds of practices. There are so many ways in which these traditions are really alive in the present.

.png)

From Karachi LaJamia’s first course, Art & Politics in the City, a session on the work of poet Shaikh Ayaz. 2015.

RS: And what is disturbing is that the imperial gaze is being used in Pakistan for its own colonialist procedures, for instance with reference to the Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) discourse. For us in India, we are very well aware of this except the context is different… I am curious about the nexus between this form of militarisation and public art and literature festivals that you speak of in War, Visuality and the Militarised City?

ZM: Yes, and what you are saying about the failure of liberal education. There were alarm bells ringing in 2013. Right now it is just khule aam (in the open)—the absolute devastation of neoliberalism and the failure of liberal thought is so visible in this moment. But we felt that really pernicious invasion of liberal thought so clearly in 2013 with the NGO-isation of the activist sphere and the NGO-isation of the Left in Pakistan. And that was a really big way in which activist worlds and Left worlds were torn apart. Then, of course, the way in which liberalism rears its head in the Zia moment of Islamisation is that segments of the cultural sphere cope with this right-wing orthodoxy by embracing privatisation. There was still this idea in the artworld that artists were somehow these subversive, edgy misfits crossing boundaries while producing and exhibiting work in really private, exclusive spaces, in retreat from the public sphere.

But then at the same time we were dealing with this post-9/11, post-“War on Terror” neoliberalism. There was a lot of international donor and aid money coming into Pakistan. One of the spaces in which it was pumping in money was in the education sphere, specifically in higher education, and through the dream of the liberal arts college. Now years later, we can see how untenable this dream was. There was this narrative being spread of liberalism and “liberal arts education” against terrorism and fundamentalism, a liberalism in Pakistan that has always been incredibly compatible with militarism. So we saw massive amounts of money from USAID etc. being put into these really securitised and sterile educational and cultural spheres, and in many ways from universities, to litfests, to large-scale public art projects, culture was used to privatise public space and to create this narrative of a dangerous, disorderly and chaotic city. These narratives carved out the space of the city through the creation of “red zones” and “no go zones,” which were then annihilated to enable real-estate development and land accumulation. So in that sense, this nexus between the military state, a global aid network/ culture, funding and land accumulation comes together—which is probably very much the case also in India—and all of this gets wrapped up and absorbed into the pre-existing ways in which the land, governance and communities are already divided, specifically along hierarchies of ethnicity, language and caste. This further shows how easily this nexus manages to work within colonial legacies of already existing fractures and fissures.

A photograph taken during Karachi LaJamia’s course Gadap Sessions held in 2016. The course was conducted in collaboration with Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance to document the ongoing struggles around development, militarisation, climate change and marginalisation of indigenous communities, knowledges and histories in the city.

RS: Can you please tell us about the name “Karachi LaJamia”? And related to that, also about The Gadap Sessions—from your website, it seems like Pahwaro Jabal (a mountain in Gadap), which is a legend but also borrows from the language (Sindhi)—I was wondering if that was a sort of working method?

ZM: When we released that statement and announced the first course that we did, we were not thinking of Karachi LaJamia as a long-term project. We were really just reacting to what we were seeing. We were just coping and trying to bring people together to cope collectively. In that moment, we quickly put together the name Karachi Art Anti-University. It is a mouthful—really hard to say—but our first course brought together so many people and there was so much interest. It was so exciting that we realised we could not stop and that we had to keep doing the work. At that point, we decided we needed a better name. We also really wanted the name to be in Urdu, and so we reached out to our friend Hajra Haider Karrar, who is a curator and whose father is a poet, writer, scholar and translator. She approached him on our behalf and asked him what he thought would be a good Urdu name for a project like this. In a really beautiful email that he wrote to us, one of the options he suggested was Karachi LaJamia. And of course La is a prefix but it is a flexible prefix—it could mean “anti” but it could mean “un” or “non,” it could be against or it could just be a negation—so we felt that was more expansive. And Karachi LaJamia articulated a refusal, while—with Jamia—also naming it as a space of education. And the etymology of the word jamia comes from this idea of coming together, of gathering—jama hona (to assemble)—so that is how we ended up switching to Karachi LaJamia.

SR: Zahra, I recently read that in Sufi Islamic philosophy there is this idea of how “La” is negation but it is also affirmation and the two sides are incomplete without the other. The negation and affirmation go hand in hand. I feel like so much of the work we do is precisely that.

Fieldwork moments from Karachi LaJamia’s course Gadap Sessions, 2016.

After the first course, we renamed ourselves Karachi LaJamia. Through the first course, we connected with a group of activists and scholars who had recently formed an activist group called the Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance. We had found out from them that there was a vast mega-development project unfolding on the outskirts of the city in this neighbourhood called Gadap. As we learned about the sheer scale of that project we realised that these massive and devastating developments happen so underhandedly and invisibly. We decided to do a course where we could centre the city through this neighbourhood of Gadap to understand and to witness these processes of development and dispossession as they unfolded and as they were being resisted.

We had reached out to late historian and scholar Gul Hasan Kalmatti, who had recently co-founded the Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance (KIRA). We shared our idea of organising a collaborative course with KIRA and he really encouraged us. We were initially very tentative and uncertain about what our engagement would look like. What can we do? What should we do? And he really really encouraged us saying “Go! You are there to document, you are there to witness that this development project, this real-estate project of Bahria Town is destroying and disappearing everything—all of our history, all of our settlements, all of our landmarks.” The developers were using the narrative that this is all banjar (barren), ghairabad (uninhabited), ghairmehfooz (unprotected) zameen (land). But in reality, it was these very developers who were turning Gadap into “a barren wasteland” by destroying and razing down everything that came in their path. And so we did an open call and we had a group of thirteen participants ultimately. The Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance collaborated with us in what ended up becoming a kind of mapping project, where over six months we visited the real estate project that was unfolding in this neighbourhood. Our sessions were led by community elders, activists, environmentalists, and we used lots of different methods of studying. The course was a seminal moment for all of us, where we really came face to face with the violence that is at the heart of making and sustaining the city. It really helped us to understand the much longer histories and forms of violence unfolding in the city. And to realise that the struggle is not only about land, but also at the level of the image, against erasure.

Fieldwork moments from Karachi LaJamia’s course Gadap Sessions, 2016.

To learn more about the recipients of this year’s awards, read Aparna Chivukula’s conversation with Jayeeta Chatterjee, Adreeta Charaborty’s conversation with Anupam Sud and Pramodha Weerasekera’s reflections on Shilpa Gupta's practice. To learn more about previous recipients, read Santasil Mallik's two part interview with Prasiit Sthapit, who won the Asia Arts Future Award (South Asia) in 2024 as well as interviews with the winners of the 2022 edition which includes Himmat Shah, Jasmine Nilani Joseph and Sumakshi Singh. Also revisit the ASAP | art podcast in which Najrin Islam speaks to Inakshi Sobti, Chief Executive Officer of the Asia Society, India.

To learn more about Karachi LaJamia, watch Anisha Baid’s three part conversation with the team on their publication Exhausted Geographies. Also read Pamudu Tennakoon’s reflections on a panel titled “Seeding a Grove of South Asian Solidarities” at Colomoboscope (2024) and Mallika Visvanathan’s observations on the exhibition 28° North and Parallel Weathers (2024).

All images by and courtesy of Karachi LaJamia.