On Partitions, Community Memory and Resistance: In Conversation with Karachi LaJamia

In the first of this two-part conversation, Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani, co-founders of the art collective in Pakistan, Karachi LaJamia, and recipients of the Asia Arts Future Award (South Asia), shared their journey from early frustrations with a nexus between a liberal university arts education and a militarised state. Through the formation of the collective, their experimentations with site-specific radical arts pedagogies and collaborations with community elders and activists who were struggling against dispossession of their lands by real-estate companies in the name of “development” enabled them to nurture politics within art and bring their activist and art communities into conversation with one another. In the second part of this interview, they share with us the double-edged sword of representation—the violence of mapping as a tool for erasures of indigenous communities while also being a method for enabling community memory, testimony and resistance. In their continued attempt to encounter, interrogate and engage with the meaning of the “nation,” they shed light on the ways in which the memorialisation of the 1947 Partition has neglected to take account of several lesser-known partitions along ethnic, caste and linguistic fissures across South Asia, the violence of which continues to sustain and maintain the nation through the enforcement of these fractures. While continuing to document and witness the ways in which community organisers struggle to protect the city’s land, coastal and riverine ecologies, the duo shares their hopes for translating their work across South Asian and global contexts.

Installation shot from Groundtruthing, an exhibition by Karachi LaJamia at Gandhara Art Gallery, Karachi 2017.

Radhika Saraf (RS): The imagination of Gadap as barren or banjar is reminiscent of how Palestine is portrayed, as an uninhabited wasteland, as if there was nothing there. Thinking in terms of the role of art, the question very often is one of representation. But if the problem is one of land and dispossession, then what did you, as artists, think of and frame as resistance?

Zahra Malkani (ZM): We were not only approaching our work with Karachi LaJamia as artists, but as teachers and people situated in institutions. For a time, we had teaching positions and were really interested in doing that and identifying that as the work of our lives. However, we were also engaged and invested in different struggles ongoing in the city. So with Karachi LaJamia, we were engaging with the work on all of these fronts, in all of the layers of our own identities, and not just as artists. And we were interested in using the tools that we have developed as artists, including the ways of seeing, thinking and relating.

For us at Karachi LaJamia the course is the work. We do not have a goal-oriented or output-oriented approach. The Gadap Sessions was supposed to be a ten-week course. Instead, it ended up being six months long because of the commitment of everyone involved. At the end of it, we had accumulated a large archive of research that was visual, sonic and textual. All the different participants were free to do what they wanted with what they had learned and documented, and many of them did. Shahana and I created a web archive and a short film, which we shared in an exhibition in Karachi. Throughout this process, we were thinking about the politics of map-making, of film and of the exhibition— questions of representation and access. The exhibition opening was an incredibly meaningful moment, both for ourselves and the Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance. They really owned the exhibition—they put it on their social media, circulated it and brought people in again and again– which was a real intervention into and repurposing of the gallery space, its usual functions and audiences. And so as someone who studied or is teaching contemporary art, we are really trained to agonise over these questions of the role of art, the role of the artist, the violence of representation etc. and to perform a certain cynicism around it all. But the coping, the dealing and the answering of those questions is a really embodied practice, which one figures out by doing together.

Installation shot from Groundtruthing, an exhibition by Karachi LaJamia at Gandhara Art Gallery, Karachi 2017.

Shahana Rajani (SR): All the pedagogical work that we have been doing has simultaneously been exploring this question of the limitations and possibilities of representation. Even in The Gadap Sessions, it was a mapping project, so visual methods were very much at the centre of the work. The research and part of the practice sought to apprehend and recognise the violence of representation and of visuality, as well as the ways in which representational practice has very material consequences for the space. In 2013 and 2014, there were all of these maps of the city that were circulating in mainstream media—they were terror maps or maps of “no-go zones.” We saw how rendering certain neighbourhoods in red helped legitimise military operations and raids by the state because, in the public imaginary, spaces like Gadap were made to be seen as dangerous and dehumanised. The map played a really key role in unfolding violence in these urban spaces.

We were also seeing how private developers of real estate projects on the peripheries of the city were erasing settlements and constantly showing these areas as empty space on the map, waiting to be populated. Early on, we came face-to-face with this very long, brutal history of representation that has unleashed so much violence on land, its custodians and communities. But at the same time, doing this work with communities, activists and community organisations, where representation practice and visuality are at the centre of storytelling, memory and testimony, showed us how it is also always being redeemed in so many ways—as sustenance and to document or witness. We have come full circle with the critique of the violence of visuality to see that representation is also the making of relation, the making of community. That is something we have really been thinking about more and more recently—that alongside this colonial history of representation there is also a beautiful and powerful community history of representation—so how can we learn from those practices and ethics of representation?

Indigenous Rights Alliance activist Khuda Dino Shah draws a map of Karachi’s rivers. This photograph was taken during Karachi LaJamia’s fieldwork for Sailaab Syllabus in 2022. Maps are central to Karachi LaJamia’s research practice, not so much as representations of space, but more so as modes of connection.

RS: Speaking to the idea of community memory and the focus on process rather than outcome, in Stateless Study—your Proposal for a Memorial to Partition—each of the four sub-projects you chose are rooted in a much larger history that goes beyond ideas of nation-building. What went into the selection of the four exercises?

ZM: In Partition remembrance practice, there is a world of representation—film, text and so on—around the 1947 partition event. Yet across the subcontinent we have experienced hundreds of lesser-known partitions. There are so many ways in which our societies and communities—ethnic minorities in Pakistan, for example—have experienced catastrophes beyond, outside or adjacent to Partition. There are very specific ways and tropes of thinking about Partition which visualise or approach Partition through the lens of very specific communities. But there are a lot of experiences of Partition or even Partition-adjacent experiences that are unheard of because of ethnic, caste and linguistic fissures across South Asia. With the Proposal for a Memorial to Partition, we were really thinking of how Karachi is often understood as a city whose history began at Partition or not long before Partition—to the erasure of communities that lived here for many generations and many centuries before 1947. And so we were thinking about that event of the Partition as a story which is nestled within all of these other stories and spaces in Karachi that pre-date and outlive that particular narrative.

Still from Jinnah Avenue, a short film by Karachi LaJamia. 2017.

RS: And yet they are very linked to what seems to be your predominant concern with land. At the shrine of the eighth-century mystic Abdullah Shah Ghazi, you say how one of his miracles was the waves dancing against the wall, but this has stopped because of land reclamation and expanding concrete. What was it like for participants of these exercises?

SR: The syllabi we developed was for an imaginary course specifically for the exhibition. We wanted to challenge or push what an art object can be or what can or cannot be displayed in a gallery. When we were approached to participate and make work, both of us immediately had our hearts set on the fact that we wanted to come up with a syllabus. We wanted it to be the kind of photocopied syllabi you get in schools and universities that is passed around and really easy to produce. We wanted to stay true to that everyday, institutional aesthetic and form. So we created a series of exercises around these sites as a way for people to think about the erasures that constitute a city and its making.

ZM: There is such a slippery slope from the telling of Partition through the despair and devastation of those who made that journey across the border to come to the space of celebrating “the sacrifices that were made for this nation-state.” The 1947 Partition was not only a moment in which a deeply catastrophic thing happened that was just terribly wrong—its violence is a cascading violence, and that violence is maintained through a machinery of representation that creates a sentimentality and centres and valorises only certain experiences of partition. For many communities in Pakistan, the tragedy of 1947 was indeed, and continues to be, the ongoing and incredibly brutal creation of Pakistan and enforcement of its borders. Borders that annihilate specific communities—their histories, languages and cultures, which is a majority of Pakistan. This border-making does not only happen in the literal borderlands—it very much happens in and across Karachi. So our approach to the Memorial for a Proposal to Partition was a memorial for the continued violence unleashed in trying to enforce this impossible idea of Pakistan.

A photograph taken during Karachi LaJamia’s course Hamare Siyal Rishte (Our Watery Relations) held in 2021. This particular workshop was facilitated by Majeed Motani of the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum, an fisher community-led organisation founded in 1998 to advocate for coastal livelihoods, water and land.

RS: The question of whose knowledge gets legitimised is also resonant in Hamare Siyal Rishte. Is the concept of eco-pedagogy what you are currently working on? But first, may I please ask what siyal means?

ZM: Siyal is fluid, liquid, dynamic, flow—a siyal rishta (relationship), a siyal thought—it is something that is in motion, unfixed, shapeshifting.

SR: We started Hamare Siyal Rishte (Our Watery Relations) in 2021 as a course organised in collaboration with the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum and the Karachi Indigenous Rights Alliance to study environmental movements in the city to protect its coastal and riverine ecologies. The course took on a life of its own and turned into a larger research project. We have been developing a series of pedagogical materials from this research that we have been exhibiting in the past two years.

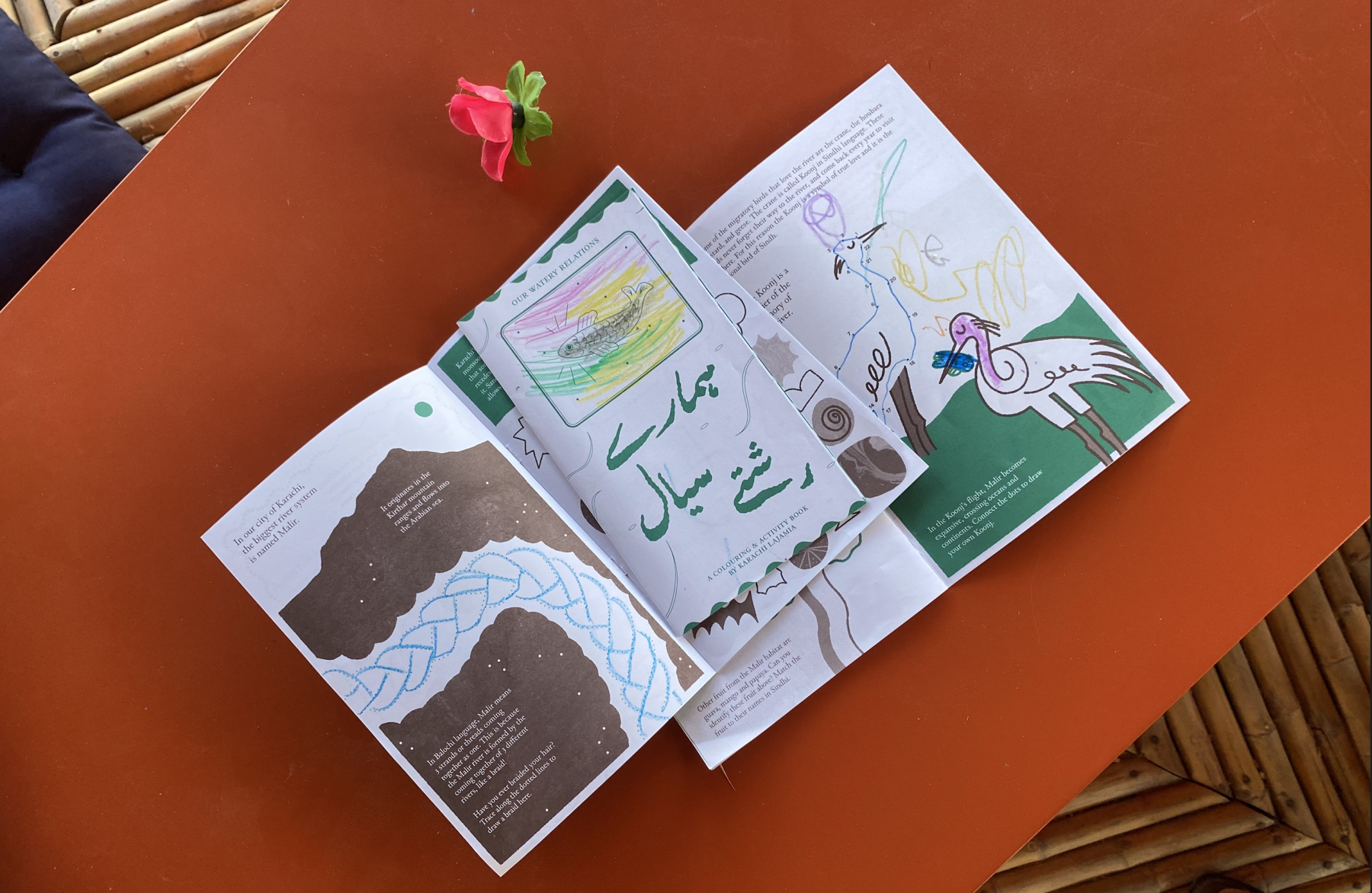

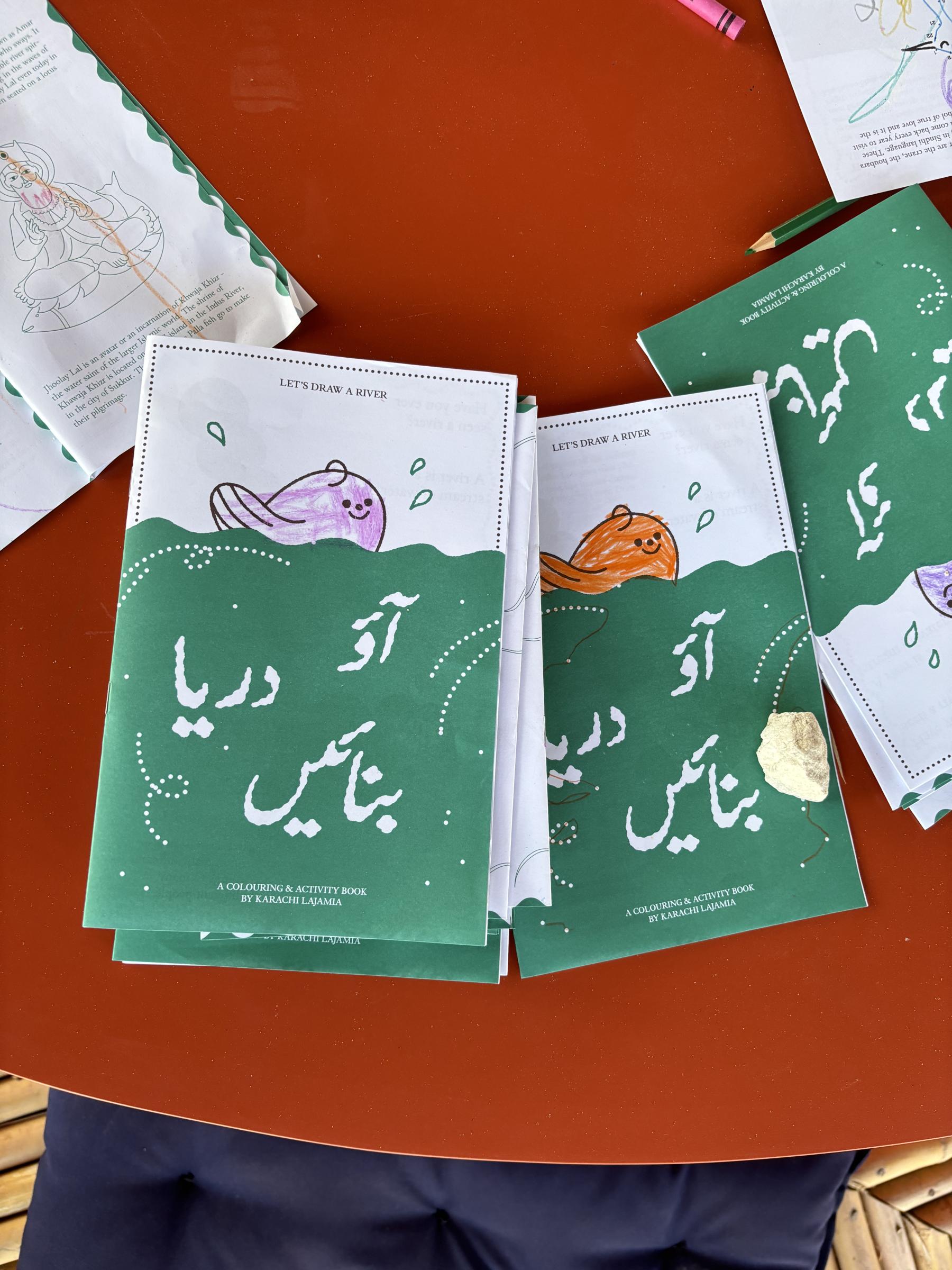

Children’s Activity Books, Hamare Siyal Rishte designed by Rose Nordin, and Aao Darya Banaaein designed by Aziza Ahmed. 2024.

ZM: It is siyal so it could be always ongoing. Even the work we did with The Gadap Sessions, we never stopped, we went to Gadap again in subsequent courses. None of our projects are really ever finished; in a very siyal way, they flow into each other and are always interconnected. With Karachi LaJamia, the work is that of creating these relationships and hopefully abiding by them—whether that is with water or with activist groups or students or community organisers. After Hamare Siyal Rishte as a course was done, we moved away (abroad). This gave us the opportunity to sit back and look at all of the work we had produced. We wanted to share it with people who are not necessarily able to attend the courses and so we created a series of children’s books. There is always more that we can do, but those decisions are dependent on the opportunities we get—in terms of funding, exhibitions and access as well. So, yes, it is still ongoing but we are also doing other stuff.

A photograph taken during Karachi LaJamia’s course Hamare Siyal Rishte (Our Watery Relations) held in 2021. This particular workshop was facilitated by Hafeez Baloch of the Sindh Indigenous Rights Alliance, tracing the rivers of the city.

RS: What has changed for you in the last ten years? Going forward, do you have anything specific in mind?

SR: Not enough has changed I would say, and that has been a hard reality to sit and deal with. But one thing that we are realising and constantly learning from our collaborators and community organisers is that no matter how persistent the violence or the repression is or how difficult and dark things are getting, the struggle continues. People continue to find ways, energies and resources to fight back and protect things that they love. I think witnessing the efforts and actions of people that we have worked with and who have been running movements and organisations for decades now is something that we are trying to always remember, centre and learn from.

Karachi LaJamia’s installation Ecstatic Ecopedagogies at 421 Arts Campus, Abu Dhabi (2024) as part of Colomboscope’s traveling exhibition “Ways of the Forest.”

ZM: Yes, politically things have only gotten worse, but over the years we have also developed this faith in doing the work. Doing the work is the means of survival, and our faith has also grown in what kind of work it is possible to do.

SR: I think one thing that has not necessarily changed but a way of working that is different for us right now is that our first few years with Karachi LaJamia were site-specific—we were very much locating ourselves in Karachi, for audiences in Karachi. In the last few years, through invitations to international conversations, dialogues and exhibitions, we have been pushed to think about the ways in which the work translates into a larger South Asian and global context. It has made us rethink what an audience means to us as we realised how much resonance the work has across borders.

Children’s Activity Books, Hamare Siyal Rishte designed by Rose Nordin, and Aao Darya Banaaein designed by Aziza Ahmed. 2024.

In case you missed the first part of the interview, read it here.

To learn more about Karachi LaJamia, watch Anisha Baid’s three part conversation with the team on their publication Exhausted Geographies. Also read Pamudu Tennakoon’s reflections on a panel titled “Seeding a Grove of South Asian Solidarities” at Colomoboscope (2024) and Mallika Visvanathan’s observations on the exhibition 28° North and Parallel Weathers (2024).

To learn more about the recipients of this year’s awards, read Aparna Chivukula’s conversation with Jayeeta Chatterjee, Adreeta Charaborty’s conversation with Anupam Sud and Pramodha Weerasekera’s reflections on Shilpa Gupta's practice. To learn more about previous recipients, read Santasil Mallik's two part interview with Prasiit Sthapit, who won the Asia Arts Future Award (South Asia) in 2024 as well as interviews with the winners of the 2022 edition which includes Himmat Shah, Jasmine Nilani Joseph and Sumakshi Singh. Also revisit the ASAP | art podcast in which Najrin Islam speaks to Inakshi Sobti, Chief Executive Officer of the Asia Society, India.

All images by and courtesy of Karachi LaJamia.