Asian Voyages: The Films of Deben Bhattacharya

Deben Bhattacharya. (Image courtesy of Wikipedia.)

In January 2025 at Sinema Transtopia in Berlin, I curated two film programmes and a listening session of ethnomusicologist, archivist, field recordist, photographer, documentary filmmaker and writer Deben Bhattacharya’s films and musical recordings. This essay is an edited version of my introductions to the sessions, with the aim that publishing these preliminary remarks on his films will introduce Bhattacharya’s rarely seen and discussed films to a wider audience. I would like to extend a word of thanks to Jharna Bose, Sushrita Acharjee, Julie Guillaumot and Paul Purgas.

Deben Bhattacharya was born in Varanasi to a Brahmin family of Sanskrit scholars in 1921. It is here that he spent his formative years and had a privileged association with a number of remarkable musicians, mainly singers of religious songs and ragas, who were family friends. He was exposed to both the North Indian classical tradition of ragas and the local folk traditions at a rather young age. Varanasi at the time allowed Bhattacharya a certain proximity to Western culture. Even in the years before it emerged as an attractive halt on the hippie trail, the ancient city drew its fair share of eccentrics from the West. One such was the British poet Lewis Thompson, who was a close friend of Bhattacharya’s. Bhattacharya did not acquire any formal academic training; he lived a nomadic life, and worked various jobs such as those of a travelling salesman, accounts clerk, news reporter and journalist, as well as interpreter for books on Indian music for Western publishers.

Hazim with rebab, Bedouin camp (left), and unidentified Bedouin coffee grinder with mortar and pestle (right). (Photographs by Deben Bhattacharya. From Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road, page 85. Image source: https://4columns.org/dayal-geeta/deben-bhattacharya)

Breaking away from his life in Varanasi in order to see the world with his own eyes, Bhattacharya left for London in 1949 and immediately sought work with the BBC Eastern Service. He hosted radio programmes accompanied by musical samples from the East. The limited archive of such samples at the time instilled in him a frustration as well as a desire to record music. Two things accelerated his foray into music recording: one was a growing interest in ethnic music and folk culture in the West in the immediate postwar period, and the other was the arrival of portable tape recorders. He undertook his first journey for recording in 1954, accompanied by Richard Lannoy—writer, painter, and photographer—on a boat. Here he sampled the music of Bauls, the mendicant singers of Bengal. Later in 1955, he would undertake an iconic trail extending 12,000 miles on a Bedford milk van turned into a caravan. Here, he was accompanied by French journalist Henri Anneville (who would drop out during the course of the journey) and British architect Colin Glennie, who was inspired to make the journey to visit Le Corbusier in Chandigarh at the time. Bhattacharya and Glennie would traverse the famed desert road—travelling through some fifteen countries—as they recorded Bedouin songs of coffee grinding in Jordan, religious Mevludin Nebevi of Turkey, Kurdish ballads of Iraq, love songs of Iran and wedding songs of Pakistan along the way. The imagination of an “ethnic” in the case of Bhattacharya was truly transnational that transgressed the understanding of culture fundamentally tied to national boundaries. As he once wrote: “There is no abrupt change or division in geographical atmosphere, the progress is in slow undulating curves unless the earth is divided by the sea, or by mountains as insurmountable as the Himalayas. And this geographical continuity, naturally, affects the people and their music too.” On this trip he collected nearly forty hours of recording.

In this period and later, Bhattacharya led the life of a committed freelancer, marked by financial precarity. He was constantly hustling gigs from the BBC and moved extensively across borders while steadily expanding his musical horizon. For example, he researched “silence” and music concrète with French composer Pierre Schaeffer in the 1970s. By 1968, he was already in possession of an Éclair NPR 16mm camera and with a budget of 3000 pounds offered to him by Harley Usill from the British record label Argo (who produced many of Bhattacharya’s early audio albums). He returned to Varanasi in the spring of 1968 to make Raga—a documentary on the classical Hindustani tradition. The half-an-hour-long film begins with an introduction by British violinist Yehudi Menuhin, followed by descriptive passages about the origin of the ragas and the manufacturing of a sitar, before an emphatic finale—a music performance in full by Ustad Halim Jaffar Khan of the Beenkar gharana (tradition/lineage) from Indore. Raga’s mix of recording and interpretation was to become a characteristic of Bhattacharya’s documentary style. In the following two-and-a-half decades, he would go on to make over twenty-five films, most of them as part of the Asian Notebook series shot in South and East Asia primarily, with the exception of two films made in Turkey and Hungary. The films were shot with modest means, though often by professional cameramen—Denny Densham from London or Gour Karmakar from Kolkata—while Bhattacharya directed, scripted and participated in recording and editing.

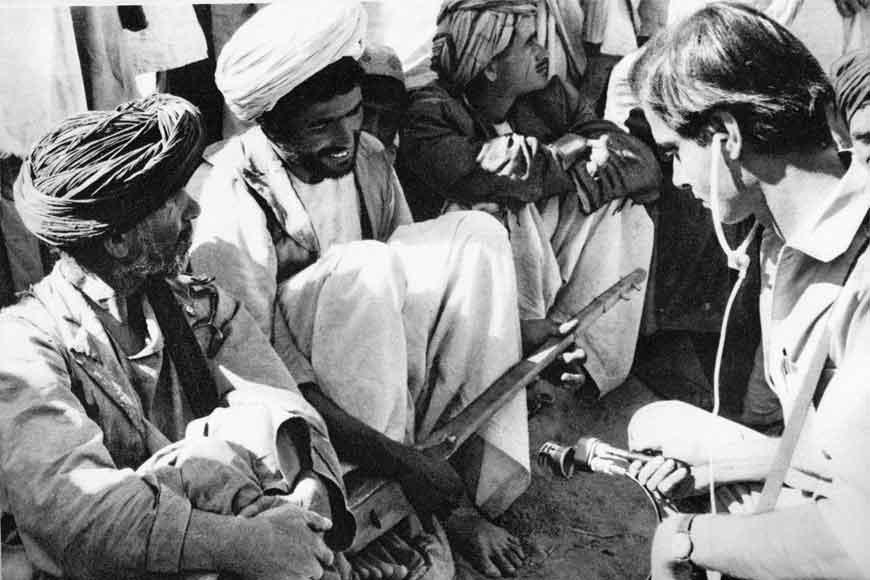

Deben Bhattacharya recording in Afghanistan, 1955. (Image source: https://www.sublimefrequencies.com/products/625798-deben-bhattacharya-paris-to-calcutta-men-and-music-on-the-desert-road)

Bhattacharya’s ideas about people and culture drew upon the quasi-romantic and transcendental idea that folk cultures and traditions outlast the inherently transient social and political changes. He was a traveller in the truest sense of the term who would deeply romanticise the lives of gypsies, who, according to him, “reflect the spirit of improvisation rather than of calculation,” moving for the sake of moving, without a concrete sense of destination. In the documentary films, which were mostly shot on 16mm and later on analogue video in the 1980s, Bhattacharya acquired the role of a mediator, an interpreter of culture, who would broker an understanding of folk cultures for a largely Western audience. This role of interpretation is carried out often by way of a didactic voiceover that comments upon the images, evoking historical narratives and seeking to establish a continuum between religious practices, labour and art in largely pre-industrial societies. Bhattacharya’s proximity to or distance from a particular society would bear upon the films. The challenge these films pose is that of historical contextualisation. One point of departure could be the British Pathé newsreels and yet another could be the whole gamut of Western ethnographic films—from the colonial-extractionist to the more critical and self-reflexive, of which ethnomusicology is a sub-genre. Through affinity or contrast, one thinks of Alan Lomax’s The Land Where the Blues Began (1979), which documents the folk music culture of the Mississippi deltas; John Cohen’s Mountain Music of Peru (1984), which explores the musical thread that runs through the Andes extending from the ancient culture of the Incas; or indeed Pachamama (1995), Peter Nestler’s extraordinary expedition through postcolonial Ecuador. Given the production and distribution history of Bhattacharya’s films—produced by British companies Argo and Seabourne Enterprises that were then broadcast on television in France and the UK, or distributed in the video format for educational purposes, save the occasional showing at a film club or a film festival—the adjacency in motive and purpose to Western ways is expected.

.png)

Deben Bhattacharya recording Santhals near Asansol in 1954. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Jharna Bose. Image source: https://www.bengalfilmarchive.com/new-documentary-3.php?i=MjI=)

However, these films also acquire a curious resonance with developmentalist narratives in national documentary productions. For example, the Films Division in India produced state documentaries about cultures considered on the fringes of its industrial and modernising aspirations, with films such as Chhau Dances of Mayurbhanj (1986) by Nirad Mohapatra. Other projects also come to mind, like the two documentary films by Ritwik Ghatak produced by the Bihar government in the 1950s, Bihar Ke Darshaniya Sthan (Bihar’s Scenic Spots, 1955) and Adivasiyon Ka Jeevan Srot (The Life Source of Adivasis, 1955), depicting the lives of the aboriginal Santal community who, across the border in Bengal, become the focus of Bhattacharya’s Faces of the Forest (1973). The German TV station ZDF produced Mani Kaul’s film A Desert of a Thousand Lines (1981) that lyrically elaborates on the living traditions of artisanal scroll painters in the state of Rajasthan, as does Bhattacharya’s film Painted Ballads of India, finished in the same year. Bhattacharya’s films can simultaneously be idealistic, politically naïve and culturally insightful about the depicted geographies and their inhabitants. They clearly seem to avoid direct political rhetoric but given the charged and dynamically transforming histories of these landscapes, is it at all possible to look at them today without thinking about the transformations they have undergone?

Still from Faces in the Forest (1973) by Deben Bhattacharya. (Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France [BnF].)

Political narratives sometimes manifest through their conspicuous absence. Faces in the Forest is from a time when such rural belts were heavily infested by the emergent far-left Naxalite movement—the present-day Indian State continues to target Adivasis in the garb of tackling an internal threat, Operation Kagar being the most recent instance. The three films Bhattacharya made in Sri Lanka—namely A Gem Called Sri Lanka (1973), Jesus and the Fishermen (1976) and Buddha and the Rice Planters (1976)—inherit the exoticising tendencies of the breathtakingly stunning The Song of Ceylon (1934) by Basil Wright. A Gem Called Sri Lanka shows a procession of decorated tuskers, adorned in expressive garments. One such elephant also features in Mark LaPore’s singularly brilliant dialogue-less portrait of war-torn Sri Lanka in A Depression in the Bay of Bengal (1996), where colonialism is invoked through a found footage travelogue film featuring another elephant, whose legs are tethered to a tree. Buddha and the Rice Planters ends with a prophetic observation about peace and harmony in the island nation among the various religious co-habitants, rendered ironic in retrospect by the onset of one of the bloodiest civil wars starting soon after and lasting for over three decades.

Still from A Gem Called Sri Lanka (1973) by Deben Bhattacharya. (Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France [BnF].)

One wonders what became of the indigenous dance-drama traditions of “Barong” and “Ketchak”—costume and mask performances replete with cosmological and zoological elements—from Bali shown in The Island of Temples (1973) since the proliferation of tourism and the sustainability challenges posed by it. His 1985 film Uighurs on the Silk Route, filmed in the barren landscapes of the Turpan prefecture, becomes an essential document of extant performing arts traditions of a persecuted minority. Bhattacharya was not a trained anthropologist and his films are anything but innocent documentations. They do not adhere to the demands of institutional forms of archiving, but perhaps this is not entirely detrimental—their slippages and deficiencies produce unexpected critical entanglements.

Still from The Island of Temples (1973) by Deben Bhattacharya. (Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France [BnF].)

To learn more about the narratives put forth by the Films Division (FD) around ideas of the nation, read Ankan Kazi’s reflections on Peter Sutoris’ book Visions of Development and his essay on the use of still and moving image experiments by filmmakers under the banner of FD.

To learn more about films and artists documenting music, read Veeranganakumari Solanki’s reflections on the work of Molla Sagar and Upasana Das’ essay on Poulomi Desai’s music practice.